More than 200 political scientists wrote an open letter to lawmakers proposing sweeping changes to federal elections. The overhaul would be a heavy lift.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

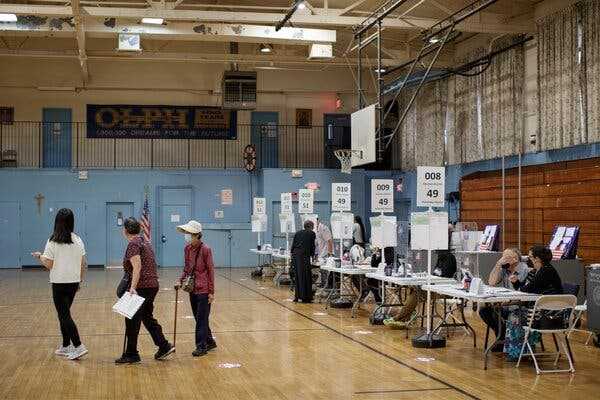

Voters in Brooklyn during a primary in August. In several states, including New York, attempts by voters to change gerrymandering have ended in disappointment.

If there’s one thing we know about America’s creaking democracy, it’s this: Whenever it seems fundamentally broken, people get together to try to fix it.

That’s happening now. We’re living through one of the United States’ periodic bursts of reformist energy, with various groups pushing to alter the structure of our elections even as — or rather because — millions of voters on both sides of our partisan divide question the integrity of the system.

The latest entry is a roster of more than 200 American political scientists who have put forward a sweeping proposal to change the way the United States has conducted its federal elections for nearly 250 years.

In a sharply written open letter to Congress published on Monday and shared in advance with The New York Times, the scholars tell lawmakers, “It is clear that our winner-take-all system — where each U.S. House district is represented by a single person — is fundamentally broken.” They call on Congress to “adopt inclusive, multimember districts with competitive and responsive proportional representation.”

The list of signatories includes nine of the 18 living U.S.-based winners of the Johan Skytte Prize, a prestigious Swedish award that has become a kind of unofficial Nobel for political science: Robert Axelrod, Francis Fukuyama, Peter J. Katzenstein, Robert Keohane, David D. Laitin, Margaret Levi, Arend Lijphart, Philippe C. Schmitter and Rein Taagepera.

“Our arcane, single-member districting process divides, polarizes and isolates us from each other,” the professors write. “It has effectively extinguished competitive elections for most Americans, and produced a deeply divided political system that is incapable of responding to changing demands and emerging challenges with necessary legitimacy.”

What the writers want (and need from Congress)

In simple terms, what these professors are proposing is a shift from …

-

Districts where voters in each of the two major parties first choose their representatives through partisan primaries, then select a single winner during the general election

… to:

-

A system in which voters choose multiple members to represent the same area, with votes allocated proportionally to the population.

That general approach is already in use in Arizona, although, importantly, the districts are still winner-take-all. But it’s widespread in other countries, and advocates argue that it dilutes the power of extremist parties.

In the Czech Republic, for instance, changes to the election system resulted in a moderate coalition government last year in spite of fears that far-right candidates were gaining momentum.

In the United States, changing the federal election system nationwide would require an act of Congress.

It would be politically tricky to pull off, to put it mildly. Article I, Section 4 of the Constitution grants states the authority to set “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives.” But it also gives Congress the power to “at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations.”

That ambiguity means there’s ample room for dispute about whether Congress or the states are the appropriate decision maker. Republicans, at least recently, have tended to argue that states ought to have the primary say in how federal candidates are elected, while Democrats are more often in favor of national-level changes.

Much depends on whose ox is being gored. Republicans have long thought they benefited from partisan gerrymandering, especially in states like Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where the G.O.P. is overrepresented in state legislatures relative to their share of statewide votes.

The letter writers argue that the change would “render gerrymandering obsolete” and “help ensure that a political party’s share of votes in an election actually determines how many seats it holds in the House.”

They also say it would dilute the impact of the Supreme Court’s recent moves to weaken the Voting Rights Act because it would empower communities of color, which often find themselves on the losing end of elections unless they make up an absolute majority of a district.

The failure of independent commissions

One factor powering the shift in favor of multimember districts is the failure of independent redistricting commissions to bring about fundamental change.

After redistricting in 2010, when Republicans used their newfound legislative majorities in many states to redraw the maps for state legislatures and House seats aggressively, Democrats vowed to even the score the next time.

In several states — especially Arizona, Michigan and New York — voters’ attempts to fix what they saw as excessive gerrymandering ended in widespread disappointment, with partisan bickering over the makeup of the commissions, the authority of elected leaders to override them and other issues.

According to the Cook Political Report, only 33 House districts are tossups, meaning that they are competitive in general elections. A further 23 districts are classified as leaning toward Democrats or Republicans, meaning that only in a wave election are they likely to change hands.

For state legislatures, the numbers are even starker. In Pennsylvania, for instance, one party or another often doesn’t even bother fielding a candidate. In 2020, before the latest remapping process, only 25 out of 218 districts of the Statehouse were decided by under 10 percentage points, according to a New York Times analysis.

European wine in an American bottle

The basic framework for change has been kicked around for years — primarily but not exclusively on the left.

Some in Congress have taken up the cause, including Representative Donald S. Beyer Jr. of Virginia, a Democrat who built his fortune through a chain of auto dealerships in the suburbs of Washington.

How Times reporters cover politics. We rely on our journalists to be independent observers. So while Times staff members may vote, they are not allowed to endorse or campaign for candidates or political causes. This includes participating in marches or rallies in support of a movement or giving money to, or raising money for, any political candidate or election cause.

Learn more about our process.

Beyer has a bill, the Fair Representation Act, that proposes multimember districts with proportional representation. The twist is that the legislators would be selected through ranked choice, a system used most recently to elect Representative Mary Peltola of Alaska in a special election.

Beyer’s bill has won praise from advocacy groups, but it has attracted only eight co-sponsors — none of them Republicans. It is not likely to move forward during this Congress, his deputy chief of staff said in an email.

But Ben Raderstorf, a policy advocate at Protect Democracy, a nonprofit group, said the broader concept of fundamental changes to the electoral system was gaining momentum.

For instance, the editorial board of The Boston Globe has endorsed it, as has Jesse Wegman, who wrote an Opinion essay in The Times on the subject. (The Times’s Opinion section is separate from the newsroom.)

“The dam is starting to break,” Raderstorf said, pointing to widespread disappointment among reformers with the results of independent redistricting.

He also noted what he called the Trump effect — the idea that the former president’s nonstop fanning of conspiracy theories and his embrace of fringe candidates, often in highly gerrymandered Republican districts, was shining a harsh light on the weaknesses of America’s winner-take-all election system.

The rest of the story

As my colleague David Leonhardt writes in a deep look at what he calls the “twin threats” to American democracy, however, partisan gerrymandering is only part of the story.

So-called geographic sorting of conservatives and liberals into rural and urban enclaves probably accounts for a greater portion of how Republicans and Democrats have become so polarized over the last half-century.

After all, Leonhardt notes, gerrymandering is not a factor in the outcomes of noncompetitive districts like New York’s 14th, an overwhelmingly Democratic area of the Bronx that Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won by nearly 45 percentage points in 2020.

ImageAlexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s safe seat allows her to raise money from all over the country and redeploy the funds to lift progressive allies.Credit…Sarahbeth Maney/The New York Times

Ocasio-Cortez’s safe seat allows her to take wildly popular positions on the left, raise grass-roots money from all over the country and then redeploy those funds to bolster challengers to lawmakers she deems insufficiently progressive.

The result is a weakening of the party establishment, a phenomenon that is even more pronounced on the right.

On the Republican side, the hollowing out of the official party organs helped give us the Trump presidency and far-right House members like Representatives Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia and Lauren Boebert of Colorado.

Many G.O.P. members of Congress now live in fear of facing a primary challenge — worries that have deepened as Trump has thrown his weight around within the party.

On paper, Trump’s track record so far this cycle is mixed. According to my colleague Alyce McFadden, who keeps a spreadsheet of his endorsements, the former president’s preferred candidates won all but a handful House primaries during this campaign season.

But often, Trump’s influence on Republican politics is more subtle. Much like the tractor beam on the Death Star, it creates a gravitational pull that leads most politicians on the right to orient their positions in his direction.

Eli Zupnick, a co-founder of Fix Our House, an advocacy project that favors proportional representation, said that moving away from a winner-take-all system would help politically homeless politicians like Representative Liz Cheney of Wyoming, who lost a Republican primary this summer, to compete and win across the country.

“Right now, we have a system where more than 90 percent of districts elect members in low-turnout primaries that reflect only the priorities of each party’s respective bases,” Zupnick said.

But the proposed changes, he said, “would force parties to compete across the country for every voter, and each district would elect representatives that truly reflect the values and priorities of that district.”

What to read

-

A New York Times/Siena College poll found Democrats faring far worse than they have in the past with Hispanic voters. But Jennifer Medina, Jazmine Ulloa and Ruth Igielnik write that, overall, the party has maintained a hold on the Latino electorate.

-

Nearly two years after Donald Trump refused to accept his defeat in the 2020 election, some of his most loyal Republican acolytes might follow in his footsteps, Reid J. Epstein writes.

-

Democrats and Republicans are running parallel campaigns, with one party emphasizing abortion and democracy, the other inflation and the economy. Jonathan Weisman writes that each side is talking past the other.

Thank you for reading On Politics, and for being a subscriber to The New York Times. — Blake

Read past editions of the newsletter here.

If you’re enjoying what you’re reading, please consider recommending it to others. They can sign up here. Browse all of our subscriber-only newsletters here.

Have feedback? Ideas for coverage? We’d love to hear from you. Email us at [email protected].

Image

Source: nytimes.com