He received ambassadorships after filling campaign coffers that led to two Bush presidencies. He later came around to backing Donald Trump.

- Share full article

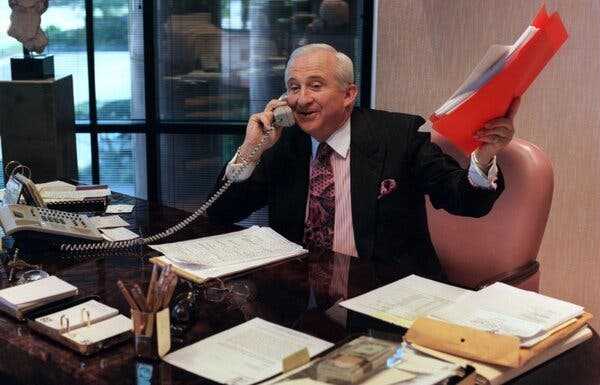

Mel Sembler in his office in St. Petersburg, Fla., in 1997. When not building shopping malls, he was helping Republicans — Dick Cheney, Newt Gingrich and Mitt Romney among them — get elected.

Mel Sembler, a gregarious developer and major Republican fund-raiser whose largess was repaid with prize ambassadorships by two presidents, and who founded a controversy-courting “tough love” drug rehabilitation program, died on Oct. 31 at his home in St. Petersburg, Fla. He was 93.

His son Brent said the cause was lung cancer.

Mr. Sembler, who developed more than 350 shopping centers and other retail projects in the Southeast, was a sought-after fund-raiser for Republicans, capable of shaking the money tree for $11 million at a single dinner. He was also an adviser to officeseekers in the G.O.P. establishment who had an open lane to power in the era before the rise of Donald J. Trump. His beneficiaries included Dick Cheney, Newt Gingrich, Mitt Romney and three members of the Bush clan.

Mr. Sembler was candid about the role of money in politics. “Money gives you a voice,” he told The Tampa Bay Times in 2019. “Without money you have no voice.”

His fund-raising spanned from the 1980s, when $100,000 was the acme of political giving, to the present era of eight-figure donations to super PACs, unleashed by the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling in 2010.

After donating more than $100,000 to George H.W. Bush’s successful 1988 presidential race and serving as chairman of his inaugural committee, Mr. Sembler was named ambassador to Australia. He served throughout President Bush’s term, from 1989 to 1993.

The appointment’s transactional nature — a political patronage ingrained in both parties — led the cartoonist Garry Trudeau to portray Mr. Sembler in a “Doonesbury” strip as the high bidder at a black-tie auction for the Australia posting.

Mr. Sembler forged especially close ties to the Bush family. As finance chairman of the Republican National Committee during the 2000 election, he wrangled more than $220 million in donations for George W. Bush and other candidates. The second President Bush named him ambassador to Italy, where he served from 2001 to 2005.

ImageMr. Sembler with former President George H.W. Bush in 2003 at a tennis tournament in Rome. Mr. Sembler was ambassador to Italy at the time, appointed by Mr. Bush’s son George W. Bush.Credit…Domenico Stinellis/Associated Press

The Sembler family once celebrated a Shabbat dinner in the White House, after which Mr. Bush, who liked to turn in early, rose from the table and said, “OK, Semblers, time to go home,” Brent Sembler recalled in an interview. Mr. Bush later worked on his memoirs in a robe on the terrace of the Sembler home. His brother Jeb liked to call Mr. Sembler’s wife, Betty, the “ambassadorable.”

For Jeb Bush, the third member of his family to run for president, Mr. Sembler oversaw donations of more than $100 million for a super PAC in 2015 — a figure so daunting that pundits predicted Mr. Bush could be unbeatable in the G.O.P. primary field that was then assembling.

But Mr. Bush, a former Florida governor, flamed out early, a victim of Republican voters’ Bush fatigue and of the populist stirrings propelling Mr. Trump, which would remake the Republican Party.

“I don’t understand our country anymore,” Mr. Sembler told The Tampa Bay Times after Jeb Bush’s early withdrawal. He said he would give “serious thought” to voting for Hillary Clinton, the Democratic nominee, in the general election.

But Mr. Sembler, like many traditional big Republican donors, came around to Mr. Trump. He was named a financial vice chairman by the Republican National Committee in 2016 to shore up donations for Mr. Trump’s campaign. He later raised money for the inauguration.

“I’m a supporter of the party, and he’s leader of my party,’’ Mr. Sembler explained two years later.

ImageMr. Sembler in 1989, when he had already begun raising money for Republicans. “Money gives you a voice,” he said. “Without money you have no voice.” Credit…Peter Rae/Fairfax Media, via Getty Images

Melvin Floyd Sembler was born in St. Joseph, Mo., on May 10, 1930, to Benjamin Sembler, a businessman, and Fanny (Magoon) Sembler, a homemaker.

Mel Sembler met Betty Schlesinger when they were students at Northwestern University, and they married in 1953. She died in 2022. In addition to his son Brent, Mr. Sembler is survived by two other sons, Martin and Greg; a sister, Delores Krakower; and 12 grandchildren.

In the early 1960s, Mr. Sembler persuaded a group of merchants in downtown Dyersburg, Tenn., to relocate to a new configuration of side-by-side stores along a highway. It was an early incarnation of the strip mall.

After moving his family to St. Petersburg in 1968, Mr. Sembler began developing shopping centers, eventually anchored by a Publix or another supermarket, in small towns across Florida. The Sembler Company went on to develop the flashier BayWalk entertainment complex in St. Petersburg and Centro Ybor, a shopping mall in Tampa.

Beginning in 1976, Mr. Sembler also funded and oversaw a chain of residential drug treatment centers for adolescents, Straight Inc., which embraced a get-tough program of confining teenagers and subjecting them to intense counseling and peer pressure.

The motivation behind the centers, according to Brent Sembler, was his parents’ discovery that one of their three sons had become dependent on drugs. An early visitor to one of the Straight centers, in the 1980s, was Nancy Reagan, the first lady at the time, who drew on the experience in creating her “Just Say No” antidrug campaign.

About a dozen centers opened in several states, but the program shut down amid controversy in 1993. A Virginia jury had awarded a former Straight Inc. resident $220,000 for being confined against his will, and a Florida jury awarded another former client $721,000 in a suit over abusive practices.

Mr. Sembler continued to support antidrug causes. In 2016 he donated at least $1 million to defeat a constitutional amendment in Florida seeking to expand access to medical marijuana. Voters passed the measure overwhelmingly.

Trip Gabriel is a national correspondent. He covered the past two presidential campaigns and has served as the Mid-Atlantic bureau chief and a national education reporter. He formerly edited the Styles sections. He joined The Times in 1994. More about Trip Gabriel

- Share full article

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Source: nytimes.com