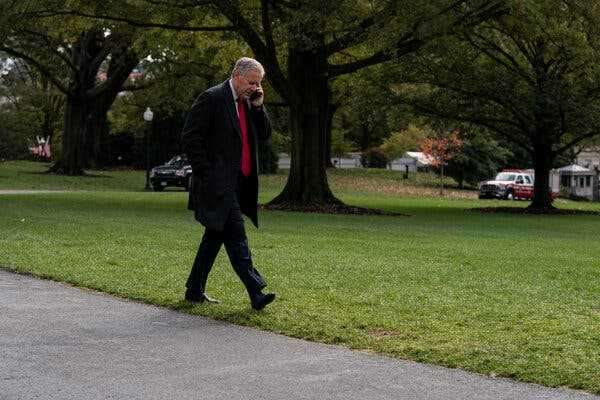

The panel sent a criminal contempt of Congress referral to the full House, as the extent of Mark Meadows’s role in President Donald J. Trump’s efforts to overturn the election became clearer.

The House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol acted after Mark Meadows, the former chief of staff for President Donald J. Trump, shifted from partially participating in the inquiry to waging a legal fight against the committee.

WASHINGTON — Mark Meadows, the last White House chief of staff for President Donald J. Trump, played a far more substantial role in plans to try to overturn the 2020 election than was previously known, and he was involved in failed efforts to get Mr. Trump to order the mob invading the Capitol on Jan. 6 to stand down, investigators for the House committee scrutinizing the attack have learned.

From a trove of about 9,000 documents that Mr. Meadows turned over before halting his cooperation with the inquiry, a clearer picture has emerged about the extent of his involvement in Mr. Trump’s attempts to use the government to invalidate the election results.

The documents also shed light on Mr. Meadows’s knowledge and guidance of a plan by right-wing lawmakers to try to use Congress to overturn the election, and on how he coordinated with organizers of the rally in Washington that culminated in the deadly riot at the Capitol.

Then, according to text messages that members of the panel read aloud on Monday, Mr. Meadows fielded dozens of requests from terrified lawmakers, administration officials and even members of Mr. Trump’s family on Jan. 6 begging for the president to call off the throngs of his supporters storming the Capitol. Mr. Meadows told people that day that he was trying to persuade Mr. Trump to do so.

The committee voted 9 to 0 on Monday evening to recommend that Mr. Meadows be charged with criminal contempt of Congress for defying its subpoena. The panel acted after he shifted from partially participating in the inquiry to waging a full-blown legal fight against the committee, in line with Mr. Trump’s directive to stonewall the investigation.

As the committee prepared to vote, Representative Liz Cheney, Republican of Wyoming and the panel’s vice chairwoman, read aloud text messages sent to Mr. Meadows by the president’s son Donald Trump Jr., lawmakers and prominent Fox News hosts beseeching him to ask Mr. Trump to put an end to the mob attack.

“He’s got to condemn this” as soon as possible, the younger Mr. Trump texted Mr. Meadows, referring to the president.

“I’m pushing hard,” Mr. Meadows responded. “I agree.”

In another, the younger Mr. Trump implored Mr. Meadows: “We need an Oval address. He has to lead now. It has gone too far and gotten out of hand.”

Ms. Cheney also quoted panicked texts from several unnamed lawmakers, including one who told Mr. Meadows, “We are under siege up here at the Capitol.”

“These texts leave no doubt,” Ms. Cheney said. “The White House knew exactly what was happening at the Capitol.”

Understand the U.S. Capitol Riot

On Jan. 6, 2021, a pro-Trump mob stormed the Capitol.

-

- What Happened: Here’s the most complete picture to date of what happened — and why.

- Timeline of Jan. 6: A presidential rally turned into a Capitol rampage in a critical two-hour time period. Here’s how.

- Key Takeaways: Here are some of the major revelations from The Times’s riot footage analysis.

- Death Toll: Five people died in the riot. Here is what we know about them.

- Decoding the Riot Iconography: What do the symbols, slogans and images on display during the violence really mean?

A contempt of Congress charge carries a penalty of up to a year in jail. The panel’s recommendation sends the matter to the full House, which could vote as early as Tuesday to refer the charge to the Justice Department.

The committee found that Mr. Meadows, a former congressman from North Carolina who led the right-wing House Freedom Caucus, essentially served as Mr. Trump’s right-hand man throughout various steps of the effort to undermine the 2020 election. Mr. Meadows encouraged members of Congress to object to Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s victory, and he pursued baseless allegations of voter fraud in several states, according to the panel.

In addition, Mr. Meadows personally coordinated with rally planners who brought throngs of Mr. Trump’s supporters to Washington on Jan. 6 to protest the president’s election loss, and Mr. Meadows said he would line up the National Guard to protect them, according to documents he provided to the panel.

At one point, an organizer of the rally turned to Mr. Meadows for help, telling him that things “have gotten crazy and I desperately need some direction. Please.”

It is not clear how he responded. The exchanges suggest that Mr. Meadows — who at times expressed personal skepticism about the claims of election fraud and theft pushed by Mr. Trump and his allies — catered to Mr. Trump by seeking evidence to support the president’s allegations. Mr. Meadows was in contact with a broad collection of obscure characters whose sometimes zany plans and theories made their way into the White House at a critical time.

Representative Bennie Thompson, Democrat of Mississippi and the chairman of the committee investigating the Capitol attack, called it “jarring” that Mr. Meadows would stop cooperating with the panel, given that he served in Congress for more than seven years.

“It’s not hard to locate records of his time in the House and find a Mr. Meadows full of indignation because, at the time, a prior administration wasn’t cooperating with a congressional investigation to his satisfaction,” Mr. Thompson said.

Before the committee’s vote, George J. Terwilliger III, Mr. Meadows’s lawyer, called on the panel to change course, arguing that it was trampling over his client’s constitutional rights and over presidential prerogatives. Mr. Terwilliger wrote in a letter to the panel that Mr. Meadows had made a “good-faith invocation of executive privilege and testimonial immunity by a former senior executive official.”

“It would ill serve the country to rush to judgment on the matter,” Mr. Terwilliger wrote.

The committee has heard testimony from more than 300 witnesses, and additional ones are scheduled to appear this week. On three occasions, the panel has moved to hold allies of Mr. Trump in criminal contempt for refusing to comply with its subpoenas.

“It comes down to this: Mr. Meadows started by doing the right thing — cooperating,” Mr. Thompson said. “When it was time for him to follow the law, come in and testify on those questions, he changed his mind and told us to pound sand. He didn’t even show up.”

Before he stopped cooperating, Mr. Meadows turned over documents that he said were not privileged, but which shed considerable light on his activities in the wake of Mr. Trump’s election defeat.

As supporters of Mr. Trump strategized about ways to keep him in power, Mr. Meadows encouraged and guided members of Congress on steps they could take to try to overturn the election, the documents show.

Understand the Claim of Executive Privilege in the Jan. 6. Inquiry

Card 1 of 8

A key issue yet untested. Donald Trump’s power as former president to keep information from his White House secret has become a central issue in the House’s investigation of the Jan. 6 Capitol riot. Amid an attempt by Mr. Trump to keep personal records secret and the indictment of Stephen K. Bannon for contempt of Congress, here’s a breakdown of executive privilege:

What is executive privilege? It is a power claimed by presidents under the Constitution to prevent the other two branches of government from gaining access to certain internal executive branch information, especially confidential communications involving the president or among his top aides.

What is Trump’s claim? Former President Trump has filed a lawsuit seeking to block the disclosure of White House files related to his actions and communications surrounding the Jan. 6 Capitol riot. He argues that these matters must remain a secret as a matter of executive privilege.

Is Trump’s privilege claim valid? The constitutional line between a president’s secrecy powers and Congress’s investigative authority is hazy. Though a judge rejected Mr. Trump’s bid to keep his papers secret, it is likely that the case will ultimately be resolved by the Supreme Court.

Is executive privilege an absolute power? No. Even a legitimate claim of executive privilege may not always prevail in court. During the Watergate scandal in 1974, the Supreme Court upheld an order requiring President Richard M. Nixon to turn over his Oval Office tapes.

May ex-presidents invoke executive privilege? Yes, but courts may view their claims with less deference than those of current presidents. In 1977, the Supreme Court said Nixon could make a claim of executive privilege even though he was out of office, though the court ultimately ruled against him in the case.

Is Steve Bannon covered by executive privilege? This is unclear. Mr. Bannon’s case could raise the novel legal question of whether or how far a claim of executive privilege may extend to communications between a president and an informal adviser outside of the government.

What is contempt of Congress? It is a sanction imposed on people who defy congressional subpoenas. Congress can refer contempt citations to the Justice Department and ask for criminal charges. Mr. Bannon has been indicted on contempt charges for refusing to comply with a subpoena that seeks documents and testimony.

“Yes,” he wrote in one message about appointing a slate of pro-Trump electors and refusing to certify Mr. Biden’s victory. “Have a team on it.”

When Mr. Trump needed someone to inspect an audit of the vote counting in Georgia or to encourage an investigation into the election in Arizona, he dispatched Mr. Meadows, who dutifully tried to carry out the president’s plans to try to undermine the election.

Mr. Meadows’s refusal to sit for an interview with the committee comes as he is promoting his new book, “The Chief’s Chief,” on television. The book contains details of White House conversations and interactions with the president.

“Mr. Meadows has shown his willingness to talk about issues related to the select committee’s investigation across a variety of media platforms — anywhere, it seems, except to the select committee,” the panel wrote in a report released on Sunday night.

The panel said it also had questions about Mr. Meadows’s use of a personal cellphone, a Signal account and two personal Gmail accounts for government business, and whether he had properly turned over records from those accounts to the National Archives.

The emails that Mr. Meadows provided to the committee showed that he discussed encouraging state legislators to appoint slates of pro-Trump electors instead of the Biden electors chosen by the voters. They also show that he encouraged Justice Department investigations of unfounded claims of voter fraud, and that he promised the National Guard would be present at the Capitol on Jan. 6 to “protect pro Trump people.”

The committee is also scrutinizing a 38-page PowerPoint document containing plans to overturn Mr. Biden’s victory. That document, which Mr. Meadows provided to the committee, included a call for Mr. Trump to declare a national emergency, and it promoted an unsupported claim that China and Venezuela had obtained control over the voting infrastructure in a majority of states.

Mr. Meadows’s lawyer has said that his client had nothing to do with the document.

Mr. Meadows could now find himself facing a criminal charge similar to another of Mr. Trump’s associates, Stephen K. Bannon, who was indicted by a federal grand jury after the House voted to recommend that he be found in contempt for refusing to cooperate with the committee. His trial is scheduled for next summer.

One by one on Monday, members of the committee assailed Mr. Meadows for refusing to share what he knew about what unfolded on Jan. 6. They said the text messages he provided made it clear that he could shed light on what Mr. Trump was doing and saying at critical times that day.

Fox News hosts were among those who contacted Mr. Meadows on Jan. 6.

“Hey Mark, the president needs to tell people in the Capitol to go home,” Laura Ingraham wrote. “He is destroying his legacy.”

“Can he make a statement?” Sean Hannity wrote to Mr. Meadows. “Ask people to leave the Capitol.”

On Jan. 7, Mr. Meadows received a text from an unnamed lawmaker who apologized for failing to overturn Mr. Trump’s loss.

“Yesterday was a terrible day,” the lawmaker wrote. “We tried everything we could in our objection to the 6 states. I’m sorry nothing worked.”

Source: nytimes.com