A noted political scientist, he saw parties periodically realigning themselves in stark fashion, presaging the rise of Donald Trump.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this articleGive this articleGive this article

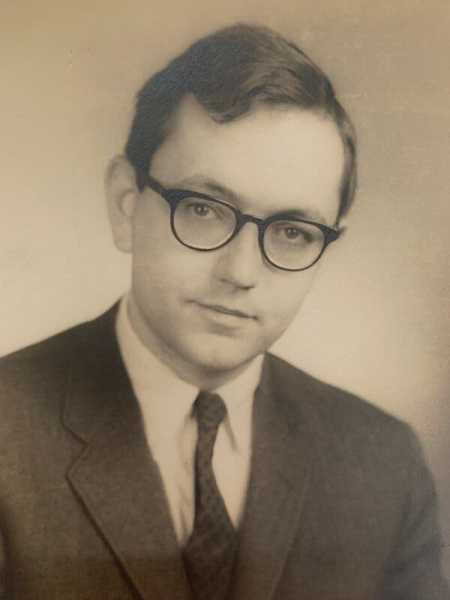

Walter Dean Burnham in an undated photo. Voters, he and a colleague wrote, “crave effective action to reverse long term economic decline and runaway economic inequality, but nothing on the scale required will be offered to them by either of America’s money-driven major parties.”

Walter Dean Burnham, a political scientist who theorized that political parties realign periodically in tectonic shifts that he called “America’s surrogate for revolution,” died on Oct. 4 in San Antonio. He was 92.

The death was confirmed by his daughter, Anne Burnham.

Professor Burnham, who taught most recently at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Texas, Austin, suggested that realignments of political parties had occurred roughly every three to four decades since 1896.

With this in mind, he said, Donald J. Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election, while “shockingly unexpected” by the news media and professional pollsters, should not have been so surprising, coming as it did 36 years after the sharp turn to the right known as the Reagan revolution.

“This was a ‘change’ election,” Professor Burnham wrote in the wake of it on the London School of Economics website. “Say what one wishes about Donald Trump’s unfitness for the presidency which he has now won, he was obviously the ‘change candidate,’ promising reactionary revitalization in response to a present deemed by himself to be intolerable.”

Enough voters agreed with Mr. Trump to give him a majority in the Electoral College, though not in the popular vote. But turnout still sagged below 60 percent of voting age Americans, a benchmark that it last topped in 1968 after falling from highs of 80 percent in the 19th century.

Professor Burnham long lamented declining turnout rates, acknowledging that while some people were undoubtedly discouraged by legal and bureaucratic hurdles to registration and voting, removing those hurdles did not necessarily improve turnout dramatically.

Instead, he attributed the historic decline in participation rates to an expanding gulf between Americans and their government, to the withering of party loyalty, and to the absence of a European-type social democratic party representing the poor and blue-collar workers.

“The growing political problem is found where the degeneration of political parties intersects with the rise of television advertising, continuous polling, media consultants and consent-massaging election operatives,” he wrote in 1988 in a letter to The New York Times.

In the presidential race that year, he added, “non-Southern turnout levels fell to their lowest point in 164 years — since before the democratization of the presidency in the Andrew Jackson era. This, I think, is the fruit of the corruption, pollution and trivialization of the electoral process in our time.”

He later found that by 2014, regional differences in turnout between the South and the rest of country had virtually vanished, for the first time since 1872.

Professor Burnham explored his ideas on political realignment and declining voter turnout in his influential article “The Changing Shape of the American Political Universe,” published in 1965 in The American Political Science Review.

He expanded those themes into a book, “Critical Elections and the Mainsprings of American Politics” (1970), which held that party realignments are typically prompted by critical elections, wars and depressions.

ImageIn this 1970 book, Professor Burnham argued that party realignments are typically prompted by critical elections, wars and depressions.

After the 2014 midterm elections, when Republicans won their largest majority in nearly a century, Professor Burnham forecast the dynamics of the presidential campaign two years later.

“Many are convinced that a few big interests control policy,” he and Thomas Ferguson of the University of Massachusetts, Boston, wrote of voters on AlterNet, a progressive website, weeks after the 2014 elections. “They crave effective action to reverse long term economic decline and runaway economic inequality, but nothing on the scale required will be offered to them by either of America’s money-driven major parties.”

Richard H. Pildes, a professor at New York University School of Law, called Professor Burnham “one of the most influential political scientists of his generation on the role and nature of political parties in American democracy.”

“Americans,” he added, “have gone through frequent eras of disdain for parties, including now, yet Burnham’s work still provides some of the most compelling rejoinders to that disdain and a powerful argument that insists on the centrality of strong parties to a healthy democratic politics. In particular, he asserted that weak parties creates weak, vulnerable legislators, which enables even greater domination of government by private interests.”

Walter Dean Burnham was born on June 15, 1930, in Columbus, Ohio, to Alfred H. Burnham Jr., an engineer for General Electric, and Gertrude (Hamburger) Burnham, a homemaker.

He received a bachelor’s degree from Johns Hopkins University in 1951 and then served in the Army as a translator of intercepted communications in Russian. He went on to earn a master’s degree and a doctorate from Harvard, where his mentor was the historian V.O. Key Jr.

He taught at Boston, Kenyon and Haverford Colleges and Washington University in St. Louis before joining the M.I.T. faculty in 1971 and the government department of the University of Texas in 1988. He became professor emeritus in 2004.

In addition to his daughter Anne, he is also survived by a son, John, and four grandchildren. His wife, Patricia (Mullan) Burnham, died in 2018.

Professor Burnham noted that political parties, for all their shortcomings, “are the only devices thus far invented which generate power on behalf of the many.”

“I guess I would like to go back not to the smoke-filled room, but to the smoke-free room,” Professor Burnham told The Times in 1988. “After all, the first president of the United States was chosen by a search process. I don’t believe the open primary system is a democratic process. A few thousand activists push the Republican Party to the right and the Democratic Party to the left.”

Alex Traub contributed reporting.

Source: nytimes.com