The development of Elon Musk’s facility in South Texas did not play out as local officials were originally told it would.

Listen to this article · 6:27 min Learn more

- Share full article

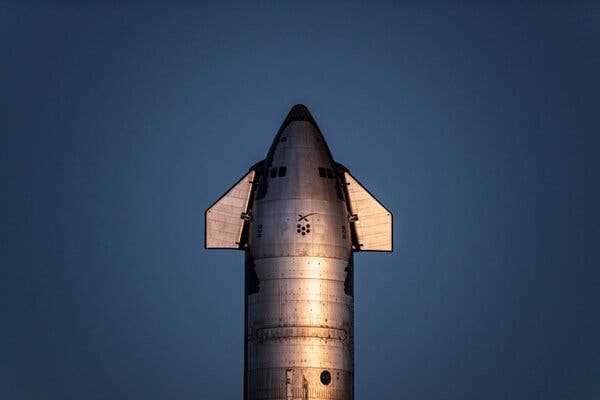

Starship, the upper stage of SpaceX’s new rocket, at its launchpad in Boca Chica, Texas. The Federal Aviation Administration wasn’t expecting a behemoth like the Starship — and didn’t initially conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the environmental impact for its size.

When Elon Musk first eyed South Texas for a new base of space operations, he promised that SpaceX would have a small, eco-friendly footprint and that the surrounding area would be “left untouched.”

A decade later, the reality is far different. An investigation by The New York Times shows how SpaceX’s ferocious growth in the area has dramatically changed the fragile landscape and has threatened the habitat that the U.S. government is charged with protecting there.

More repercussions are likely coming, in South Texas and in other places where SpaceX is expanding. Mr. Musk has said he hopes to one day launch his Starships — the largest rocket ever manufactured — a thousand times a year.

Executives from SpaceX declined repeated requests to comment. But Gary Henry, who until this year served as a SpaceX adviser on Pentagon launch programs, said the company was aware of concerns about SpaceX’s environmental impact and was committed to addressing them.

Here are four takeaways from our investigation:

Musk used preserved lands as a buffer for SpaceX operations

Rocket launch sites in the U.S., such as Vandenberg Space Force Base in California and Kennedy Space Center in Florida, typically are enormous, secure facilities with tens of thousands of acres within their confines.

Mr. Musk didn’t intend to buy up anything like that amount of land when he was looking at the area near Brownsville, Texas. Instead, he wanted to buy a tiny piece of property in the middle of public lands — what the team involved referred to as a “doughnut hole.” He figured the surrounding state parks and federal wildlife preserves would serve as natural buffers.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Source: nytimes.com