May 18, 2022, 7:00 p.m. ETMay 18, 2022, 7:00 p.m. ET

Blake Hounshell

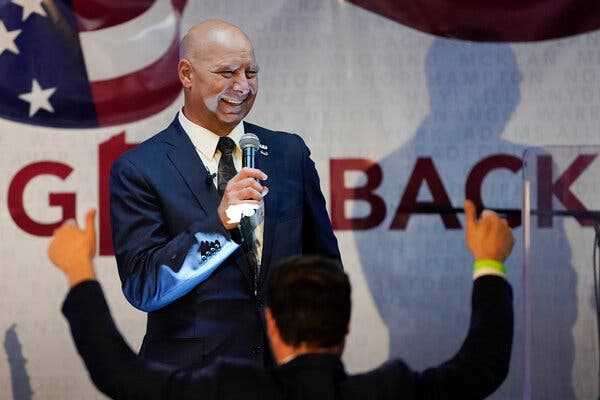

State Senator Doug Mastriano after winning the Republican nomination for governor of Pennsylvania on Tuesday.

The aftershocks of Tuesday’s big primaries are still rumbling across Pennsylvania, but one impact is already clear: Republican voters’ choice of Doug Mastriano in the governor’s race is giving the G.O.P. fits.

Conversations with Republican strategists, donors and lobbyists in and outside of Pennsylvania in recent days reveal a party seething with anxiety, dissension and score-settling over Mastriano’s nomination.

In the run-up to Tuesday night, Republicans openly used words and phrases like “suicide mission,” “disaster” and “voyage of the Titanic” to convey just what a catastrophe they believed his candidacy will be for their party.

An adviser to several Republican governors, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said there was wide displeasure with the outcome, calling him unelectable. The Mastriano campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Some in Pennsylvania blame Jeff Yass, a billionaire options trader and the state’s most powerful donor, for sticking with Bill McSwain for governor despite Donald Trump’s blistering anti-endorsement; others point the finger at Lawrence Tabas, the state party chairman, for failing to clear the field; still others say that Trump should have stayed out of the race altogether instead of endorsing Mastriano. Tabas did not respond to a request for comment on Wednesday.

An 11th-hour effort to stop Mastriano failed when both McSwain and Dave White, a self-funding candidate who spent at least $5 million of his own money, refused to drop out and support former Representative Lou Barletta, whose supporters insisted he was the more viable option.

Many Republicans thought that idea was futile and far too late; several said a serious effort to prevent Mastriano from winning should have begun last summer, while others said that Yass and his allies could have dropped McSwain sooner.

“Had they kept their powder dry, they could have seen the lay of the land, when Mastriano’s lead was 8-10, and backed Barletta,” said Sam Katz, a former Republican candidate for governor who now backs Josh Shapiro, the Democratic nominee.

“Had they spent $5 million in three weeks, they might have forced Trump to make a different choice and changed everything,” Katz added.

Mastriano had amassed nearly 45 percent of the vote as of Wednesday afternoon.

Matthew Brouillette, head of Commonwealth Partners, which bankrolled McSwain’s campaign, noted that his organization also backed Carrie DelRosso, who won the lieutenant governor’s race. He said the criticism was coming largely from “consultants and rent-seekers who don’t like us as we disrupt their gravy trains.”

After the Pennsylvania and North Carolina Primaries

May 17 was the biggest day so far in the 2022 midterm cycle. Here’s what we’ve learned.

- Trump’s Limits: The MAGA movement is dominating Republican primaries, but Donald J. Trump’s control over it may be slipping.

- ‘Stop the Steal’ Endures: G.O.P. candidates who aggressively cast doubt on the 2020 election have fared best, while Democratic voters are pushing for change. Here are more takeaways.

- Trump Endorsements: Most of the candidates backed by the former president have prevailed. However, there are some noteworthy losses.

- Up Next: Closely watched races in Georgia and Alabama on May 24 will offer a clearer picture of Mr. Trump’s influence.

Ties to Jan. 6 and QAnon

Mastriano’s vulnerabilities are legion, G.O.P. operatives lament.

The state senator and retired U.S. Army colonel has taken a hard line on abortion, which he has said should be illegal under all circumstances. He organized buses to Washington for the Jan. 6, 2021, rally in Washington and can be seen on video crossing police lines at the Capitol as the rally became a riot. He has also been a leading advocate of the baseless claims that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump.

Mastriano’s name has appeared in documents released by the committee investigating the Capitol riot, and he claims to have been in close personal contact with Trump about their shared drive to overturn President Biden’s victory. In February, the committee demanded “documents and information that are relevant to the select committee’s investigation” in a letter to Mastriano. He has refused to say whom he would appoint as secretary of state, a critical position overseeing election infrastructure and voting.

Mastriano has appeared at events linked to QAnon, the amorphous conspiracy theory that alleges there is a secret cabal of elite pedophiles running the federal government and other major U.S. institutions. He also has made statements that veer into Islamophobia.

He is likely to be an especially weak candidate in the crowded suburbs around Philadelphia, the state’s most important political battleground. On the other side of the state, the editorial page of The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette has already all but officially endorsed Shapiro as “the only statewide candidate who did everything the Pennsylvania way.”

Operatives in both parties expect Shapiro to blitz Mastriano with advertising portraying him as a dangerous extremist while Mastriano’s shoestring organization struggles to raise money.

Even before Mastriano clinched the nomination, Shapiro’s campaign aired an ad highlighting his views on abortion and the 2020 election as well as his ties to Trump, who lost the state to Biden by 80,000 votes.

Mastriano gave scant indication during Tuesday’s victory speech that he was ready to shift toward a more palatable general election message. Listing his early priorities as governor, he said, “mandates are gone,” “any jab for job requirements are gone,” critical race theory is “over,” “only biological females can play on biological female teams” and “you can only use the bathroom that your biological anatomy says.”

The Mastriano matchup also plays to Shapiro’s carefully cultivated image as a fighter for democracy, though his campaign plans to focus primarily on bread-and-butter economic issues such as jobs, taxes and inflation.

As attorney general, Shapiro was directly involved in the Pennsylvania government’s litigation after the 2020 election, and oversaw at least 40 cases of alleged voter fraud — winning every single one.

ImageJosh Shapiro campaigning in Meadville, Pa.Credit…Jeff Swensen for The New York Times

Wait-and-see mode

Will national Republicans help Mastriano or shun him? Right now, the major players in governor’s races appear to be waiting to see how the race develops before making that determination.

Some Republicans believe the national “tailwinds” blowing in their favor might help Mastriano win despite all of his weaknesses, but for now, Democrats are thrilled to be facing him in November. They note that Shapiro performed better than Biden did in Pennsylvania during his re-election race as state attorney general, and expect Shapiro to be flooded with donations from in and outside the state.

On Tuesday night, the Republican Governors Association issued a lukewarm statement acknowledging Mastriano’s victory, but suggesting he was on his own for now.

“Republican voters in Pennsylvania have chosen Doug Mastriano as their nominee for governor,” Executive Director Dave Rexrode said. “The R.G.A. remains committed to engaging in competitive gubernatorial contests where our support can have an impact.”

The statement left room for the possibility that the G.O.P. governors might help Mastriano should the Pennsylvania race be close in the fall.

Understand the 2022 Midterm Elections

Card 1 of 6

Why are these midterms so important? This year’s races could tip the balance of power in Congress to Republicans, hobbling President Biden’s agenda for the second half of his term. They will also test former President Donald J. Trump’s role as a G.O.P. kingmaker. Here’s what to know:

What are the midterm elections? Midterms take place two years after a presidential election, at the midpoint of a presidential term — hence the name. This year, a lot of seats are up for grabs, including all 435 House seats, 35 of the 100 Senate seats and 36 of 50 governorships.

What do the midterms mean for Biden? With slim majorities in Congress, Democrats have struggled to pass Mr. Biden’s agenda. Republican control of the House or Senate would make the president’s legislative goals a near-impossibility.

What are the races to watch? Only a handful of seats will determine if Democrats maintain control of the House over Republicans, and a single state could shift power in the 50-50 Senate. Here are 10 races to watch in the House and Senate, as well as several key governor’s contests.

When are the key races taking place? The primary gauntlet is already underway. Closely watched races in Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Georgia will be held in May, with more taking place through the summer. Primaries run until September before the general election on Nov. 8.

Go deeper. What is redistricting and how does it affect the midterm elections? How does polling work? How do you register to vote? We’ve got more answers to your pressing midterm questions here.

“We make those decisions based on where we think we can be effective,” Gov. Pete Ricketts of Nebraska, the co-chairman of the governors’ group, said on CNN on Sunday. “Our policy has long been we get involved in races where we think we can win. So, that candidate, whoever gets elected in Pennsylvania, will have to show that they’re going to make it a good race.”

Image

What to read

-

In primaries so far, Republican voters have appeared willing to nominate proponents of Donald Trump’s election falsehoods, making clear that this year’s races may well affect future elections, Reid Epstein writes.

-

The Make America Great Again movement is dominating Republican primaries, Michael C. Bender and Maggie Haberman write. But is the former president in control of it?

-

Jazmine Ulloa spoke with Chuck Edwards, the state lawmaker who ousted Representative Madison Cawthorn last night in western North Carolina.

-

A group is seeking to disbar Senator Ted Cruz of Texas for his involvement in the effort to overturn the 2020 election, Maggie Haberman scoops.

Image

On the record

ImageMalcolm Kenyatta at a breakfast for Democratic candidates in Boalsburg, Pa., in April.Credit…Marc Levy/Associated Press

It all comes down to turnout. Young turnout.

Of the many unknowns hanging over the general election contests across the country this fall, a big one for Democrats is: Will young progressives turn out?

The question haunts many party leaders, who worry that widespread disillusionment with President Biden and with politics more broadly will lead many younger voters to stay home in November. That’s the traditional pattern in midterm elections, and it is what happened in the Virginia governor’s race last year. It’s a constant source of frustration for Democratic strategists, since younger voters lean left.

Malcolm Kenyatta, a dynamic 31-year-old state representative who lost to Lt. Gov. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania in the state’s Democratic primary for an open Senate seat, went straight to that point when I met him at his watch party last night in Philadelphia.

Kenyatta had the backing of the Working Families Party, a scrappy progressive outfit centered in New York that supports like-minded candidates. Its leftist politics are vastly different from Biden’s centrism, but the group tends to rally behind the Democratic Party’s official nominees once primaries end.

So it didn’t surprise me when Kenyatta urged his followers to unite behind Fetterman, who also swims in many of the same leftward circles, but has tried to transcend his image as a Bernie Sanders-style progressive as the general election ramps up.

Kenyatta told me he would do his “level best” to help unite the party.

“The only fault line that exists is between people who care about democracy and those who are autocratic, racist fascists who want to turn this nation into something that it’s never been,” Kenyatta said.

The argument Kenyatta would make to young voters who might be souring on the Democratic Party, he said, was that “when you elect a bigger, bolder Democratic majority,” it makes it easier to pass major progressive priorities like universal prekindergarten and student debt relief.

Kenyatta, a gay Black man who recently married his longtime partner, said he was confident that Republican candidates were out of the cultural mainstream.

“Most people do not want to ban books and cancel Elmo and Mickey Mouse,” he said. “Most Americans think that’s ridiculous.”

Image

— Blake

Is there anything you think we’re missing? Anything you want to see more of? We’d love to hear from you. Email us at [email protected].

Source: nytimes.com