A citizen ballot initiative took redistricting out of the hands of partisan legislators. The result: competitive political districts — and an example of how to push back against hyperpartisanship.

Voters casting ballots in Detroit on Election Day in 2020. Michigan’s new districts will much more closely reflect the overall partisan makeup of the state.

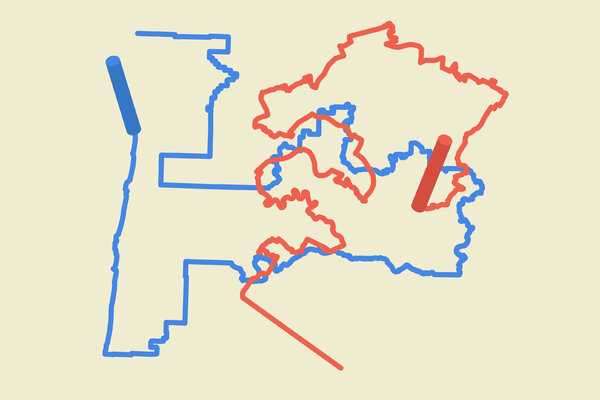

One of the country’s most gerrymandered political maps has suddenly been replaced by one of the fairest.

A decade after Michigan Republicans gave themselves seemingly impregnable majorities in the state Legislature by drawing districts that heavily favored their party, a newly created independent commission approved maps late Tuesday that create districts so competitive that Democrats have a fighting chance of recapturing the State Senate for the first time since 1984.

The work of the new commission, which includes Democrats, Republicans and independents and was established through a citizen ballot initiative, stands in sharp contrast to the type of hyperpartisan extreme gerrymandering that has swept much of the country, exacerbating political polarization — and it may highlight a potential path to undoing such gerrymandering.

With lawmakers excluded from the mapmaking process, Michigan’s new districts will much more closely reflect the overall partisan makeup of the hotly contested battleground state.

“Michigan’s a jump ball, and this is a jump-ball map,” said Michael Li, a senior counsel who focuses on redistricting at the Brennan Center for Justice. “There’s a lot of competition in this map, which is what you would expect in a state like Michigan.”

The commission’s three new maps — for Congress, the State House and the State Senate — restore a degree of fairness, but there were some notable criticisms. All of the maps still have a slight Republican advantage, in part because Democratic voters in the state are mostly concentrated in densely populated areas. The map for the State House also splits more than half of the state’s counties into several districts, despite redistricting guidelines that call for keeping neighboring communities together.

The maps may also face a legal challenge from Black voters in the Detroit area, to whom the commission tried to give more opportunities for representation by unpacking them, or spreading them among more legislative districts.

Redistricting at a Glance

Every 10 years, each state in the U.S is required to redraw the boundaries of their congressional and state legislative districts in a process known as redistricting.

- Redistricting, Explained: Answers to your most pressing questions about redistricting and gerrymandering.

- Breaking Down Texas’s Map: How redistricting efforts in Texas are working to make Republican districts even more red.

- G.O.P.’s Heavy Edge: Republicans are poised to capture enough seats to take the House in 2022, thanks to gerrymandering alone.

- Legal Options Dwindle: Persuading judges to undo skewed political maps was never easy. A shifting judicial landscape is making it harder.

Detroit’s State Senate delegation will jump to nine members from five, and its State House delegation to 15 representatives from nine. But local Black elected officials and civil rights groups contend that while the intention may have been noble, the result actually dilutes Black voting strength, not only in general elections but also in primaries, in which elections for Black legislators are almost always decided.

The reduced percentages of Black voters in some of the new districts may prevent candidates from winning primary elections on the strength of the Black vote alone, those critics say.

“The goal of creating partisan fairness cannot so negatively impact Black communities as to erase us from the space,” said Adam Hollier, a state senator from the Detroit area. “They think that they are unpacking, because that is the narrative that they hear from across the country, without looking at what that means in the city of Detroit.”

Republicans were also discussing possible challenges to the new maps.

“We are evaluating all options to take steps necessary to defend the voices silenced by this commission,” Gustavo Portela, a Michigan G.O.P. spokesman, said in a statement Wednesday, without elaborating on whose voices he meant.

The G.O.P. advantage in Michigan’s Legislature has held solid for years even as Democrats carried the state in presidential elections and won races for governor and U.S. Senate. In 2014, Senator Gary Peters, a Democrat, won the seat formerly held by Carl Levin by more than 13 percentage points. Yet in the same year, Republicans in the State Senate expanded their supermajority, winning 27 of 38 seats.

So great a divergence between statewide and legislative elections is often a telltale sign of a gerrymandered map. And a lawsuit in 2018 unearthed emails in which Republicans boasted about packing “Dem garbage” into fewer districts and ensuring Republican advantages “in 2012 and beyond.”

But the new State Senate map would create 20 seats that President Biden would have carried in 2020 and 18 that former President Donald J. Trump would have carried, giving Democrats new hopes of competitiveness.

The new maps offer no guarantee that Democrats will win either chamber, however. And in a strong year for the G.O.P., which 2022 may be, Republicans could retain their advantage in the Legislature and could also come away with a majority of the state’s new 13-seat congressional delegation.

The congressional map includes three tossup seats where the 2020 presidential margin was less than five points, and two more seats that could be competitive in a wave year, with presidential margins of less than 10 points. Two current Democratic representatives, Haley Stevens and Andy Levin, were drawn into the same district, setting up a competitive primary in the 11th District. Both declared their intention to run on Tuesday.

The State House will also feature at least 20 competitive districts.

Preserving such competition, election experts say, is one of the key goals in redistricting reform.

“This is the quintessential success story of redistricting,” said Sam Wang, director of the Princeton Gerrymandering Project. “These maps treated the two parties, Democrats and Republicans, about as fairly as you could ever imagine a map being. In all three cases, whoever gets the most votes statewide is likely to control the chamber or the delegation. And there’s competition in all three maps.”

Understand How U.S. Redistricting Works

Card 1 of 8

What is redistricting? It’s the redrawing of the boundaries of congressional and state legislative districts. It happens every 10 years, after the census, to reflect changes in population.

Why is it important this year? With an extremely slim Democratic margin in the House of Representatives, simply redrawing maps in a few key states could determine control of Congress in 2022.

How does it work? The census dictates how many seats in Congress each state will get. Mapmakers then work to ensure that a state’s districts all have roughly the same number of residents, to ensure equal representation in the House.

Who draws the new maps? Each state has its own process. Eleven states leave the mapmaking to an outside panel. But most — 39 states — have state lawmakers draw the new maps for Congress.

If state legislators can draw their own districts, won’t they be biased? Yes. Partisan mapmakers often move district lines — subtly or egregiously — to cluster voters in a way that advances a political goal. This is called gerrymandering.

What is gerrymandering? It refers to the intentional distortion of district maps to give one party an advantage. While all districts must have roughly the same population, mapmakers can make subjective decisions to create a partisan tilt.

Is gerrymandering legal? Yes and no. In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal courts have no role to play in blocking partisan gerrymanders. However, the court left intact parts of the Voting Rights Act that prohibit racial or ethnic gerrymandering.

Want to know more about redistricting and gerrymandering? Times reporters answer your most pressing questions here.

The path to an independent redistricting commission in Michigan began with a Facebook post days after the 2016 election from a woman with no political experience.

“I’d like to take on gerrymandering in Michigan,” the woman, Katie Fahey, wrote. “If you’re interested in doing this as well, please let me know.”

That post started a movement. Soon, a 5,000-member volunteer organization, Voters Not Politicians, was coordinating online through Facebook messages and Google documents, organizing a ballot initiative campaign and crisscrossing the state to gin up support. Members wrote folk songs and dressed up in costumes as gerrymandered districts to draw attention to the effort.

Republicans sued to block the ballot initiative but were denied by the state Supreme Court in August 2018. That November, the measure passed overwhelmingly, with more than 61 percent of Michigan voters approving the creation of an independent redistricting commission.

“This is about voters taking our power back,” said Nancy Wang, the executive director of Voters Not Politicians. “All we wanted to do was get to where we are now.”

How Maps Reshape American Politics

We answer your most pressing questions about redistricting and gerrymandering.

Not all independent commissions have been so successful. In Virginia, a commission deadlocked and failed to produce maps, punting the process to the state Supreme Court, which approved new maps this week. In Ohio, the Republican-led legislature ignored the state’s redistricting commission and drew an aggressively gerrymandered map all but certain to cement G.O.P. control for a decade.

In Michigan, by contrast, no politicians or legislators sat on the 13-member commission; members were volunteers drawn at random. And any map approved required an overall majority as well as the support of at least two independents, two Democrats and two Republicans.

Ms. Wang, of Voters Not Politicians, said Michigan could serve as a model for others to follow.

“My hope is that, as a package, as a whole process, people can see Michigan and us having gone through this entire cycle and having come out the other end so successfully,” she said, “that there are going to be pieces of our model that get adopted in other states.”

Source: nytimes.com