Lawmakers in both parties fear that the rebellion by the extreme right could endanger spending bills and other big legislative initiatives if it persists, shaping the speakership in the most difficult of ways.

- Give this article

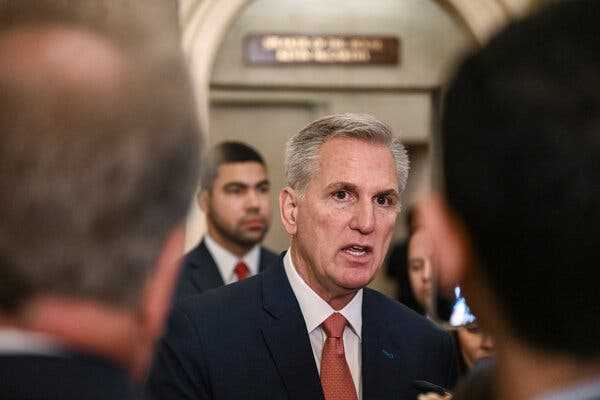

The blowback to the Republican leadership was set off by fury on the right at Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s handling of the debt limit package.

With his right flank in open revolt and keeping a stranglehold on the House floor, Speaker Kevin McCarthy faces two unappealing choices for how to govern.

He can cater to the demands of hard-right members of his conference, pushing through bills that will face a bipartisan legislative buzz saw in the Senate. Or he can steer around them on crucial issues, teaming up with Democrats to pass spending bills and other vital measures, and contend with constant threats to his job from his own party — if not outright removal.

The surprise attack on the G.O.P. leadership this week by nearly a dozen extreme right Republicans shut down the House with no resolution in sight, sidelining the party’s political messaging bill on gas stoves that was never going to become law. But it also created a paralyzing political quandary for Mr. McCarthy that foreshadows much bigger problems.

The right-wing faction’s tool of choice for the rebellion — opposing a routine procedural measure known as a rule that is normally a strict party-line vote — was a reminder that, in a closely divided House, the group could easily wreak havoc with the annual spending bills that are beginning to take shape now that the debt limit crisis is over.

Members of both parties are worried that such tactics could lead to a stalemate over those bills, prompting a government shutdown this fall and an automatic cut in spending next year that they fear would significantly undermine Ukraine in its conflict with Russia and hurt other federal programs as well.

“I’ve got serious concerns as we go into the appropriations process about how antics like this taking down a rule can impact the ability for us to do our basic job of funding the government,” said Representative Steve Womack of Arkansas, a senior Republican member of the Appropriations Committee. “It was already going to be a pretty heavy lift, but it is a lift that is going to be made heavier if this is what we are going to be facing.”

Other major legislative initiatives such as an emerging farm bill, the annual Pentagon policy measure and renewal of Federal Aviation Administration programs could also get swept into the fight, but it is the spending bills that are at the forefront at the moment.

The blowback to the Republican leadership was set off by fury on the right at Mr. McCarthy’s handling of the debt limit package, a compromise he struck with President Biden that passed the House last week with more Democratic than Republican votes. Members of the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus and other Republicans felt betrayed and complained that the agreement fell far short of the spending cuts Mr. McCarthy promised as he fought for the speakership in January.

Some of those critics now say the leadership must commit to enacting deeper cuts through the 12 annual spending measures, holding spending below the limits agreed to in the debt limit deal.

The problem for Mr. McCarthy is that if he capitulates to the hard right on spending, he most likely forfeits any chance of winning Democratic support for the bills, meaning he would have to pass them with only Republican votes when many conservatives reflexively balk at spending bills.

But party-line spending bills that could earn the approval of far-right mutineers — including Representatives Chip Roy of Texas, Ralph Norman of South Carolina and Ken Buck of Colorado — have no chance at all of passing the Democratically controlled Senate. Even leading Senate Republicans see the Pentagon funding agreed to in the debt limit package as far too low and say it must be supplemented to keep Ukraine in the field against Russia.

On the other hand, Mr. McCarthy could try to find consensus with Democrats on the spending bills — historically a bipartisan process — but then face the wrath of conservative Republicans who do not want to see any reaching across the aisle. They say Mr. McCarthy must choose between them or Representative Hakeem Jeffries of New York, the Democratic leader, who gave his blessing for his party to help push through the rule to allow the debt limit agreement to come up when Republicans withheld their votes to try to block it.

“We’re going to force him into a monogamous relationship with one or the other,” Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida, one of the 11 Republicans who tied up the floor this week, said of Mr. McCarthy on the podcast hosted by Stephen K. Bannon.

On Thursday, Mr. Gaetz said some of the insurgents had engaged in “encouraging” talks with Representative Steve Scalise of Louisiana, the majority leader, about resolving the dispute, mainly centered on “how we’re going to think about the appropriations process.”

The fight over the spending bills is especially fraught since the debt limit agreement included a provision that says spending will be cut by 1 percent across the board in 2025 if Congress fails to pass the 12 appropriations bills by Jan. 1. That arrangement was devised as a way to enforce the compromise and hailed as an incentive for Congress to do a better job of considering the individual spending measures, which has not happened in years.

Now, those responsible for writing the spending bills see the autopilot approach as a possibly dangerous outcome, since House conservatives might relish the chance to prompt the automatic cuts, even in defense programs — a prospect alarms Senate military hawks.

“With the debt ceiling issue behind us, the challenge that lies ahead is to have some semblance of a regular appropriations process,” Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the minority leader, said on Wednesday. “It’s going to require a lot of bipartisan cooperation to do what we need to do in the coming months.”

But bipartisan cooperation is exactly what Mr. McCarthy’s far-right wing says it does not want.

On Thursday, Mr. Jeffries flatly ruled out his party supporting any spending bills that come in below the level agreed to in the debt limit legislation but offered to work with Republicans to advance bills that were acceptable to Democrats.

“In terms of the way out,” he said, “House Republicans are going to have to decide whether they’re going to be responsible public policymakers or continue to bend the knee to the extreme MAGA Republicans in their party.”

For Republicans, it is much too early to consider a pact with Democrats. They view the revolt as a temporary distraction they can overcome.

“Governing always has its challenges,” Mr. Scalise said, “and we just work through ’em.”

Carl Hulse is chief Washington correspondent and a veteran of more than three decades of reporting in the capital. @hillhulse

- Give this article

Source: nytimes.com