The judge, an appointee of President Donald J. Trump, indicated she was prepared to grant Mr. Trump’s request for an arbiter, or special master, to review the documents seized by the F.B.I.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

- Read in app

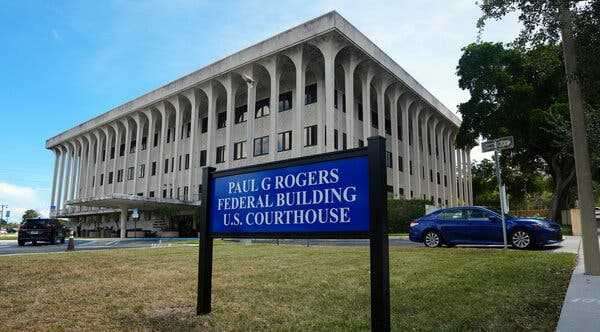

Judge Aileen M. Cannon set a hearing for arguments in the matter for Thursday in the federal courthouse in West Palm Beach, Fla.

A federal judge in Florida gave notice on Saturday of her “preliminary intent” to appoint an independent arbiter, known as a special master, to conduct a review of the highly sensitive documents that were seized by the F.B.I. this month during a search of Mar-a-Lago, former President Donald J. Trump’s club and residence in Palm Beach.

In an unusual action that fell short of a formal order, the judge, Aileen M. Cannon of the Federal District Court for the Southern District of Florida, signaled that she was inclined to agree with the former president and his lawyers that a special master should be appointed to review the seized documents.

But Judge Cannon, who was appointed by Mr. Trump in 2020, set a hearing for arguments in the matter for Thursday in the federal courthouse in West Palm Beach — not the one in Fort Pierce, Fla., where she typically works.

On Friday night, only hours after a redacted version of the affidavit used to obtain the warrant for the search of Mar-a-Lago was released, Mr. Trump’s lawyers filed court papers to Judge Cannon reiterating their request for a special master to weed out documents taken in the search that could be protected by executive privilege.

Mr. Trump’s lawyers had initially asked Judge Cannon on Monday to appoint a special master, but their filing was so confusing and full of bluster that the judge requested clarifications on several basic legal questions. The notice of intent by Judge Cannon was seen as something of a victory in Mr. Trump’s circle.

Takeaways From the Affidavit Used in the Mar-a-Lago Search

Card 1 of 4

Takeaways From the Affidavit Used in the Mar-a-Lago Search

The release on Aug. 26 of a partly redacted affidavit used by the Justice Department to justify its search of former President Donald J. Trump’s Florida residence included information that provides greater insight into the ongoing investigation into how he handled documents he took with him from the White House. Here are the key takeaways:

Takeaways From the Affidavit Used in the Mar-a-Lago Search

The government tried to retrieve the documents for more than a year. The affidavit showed that the National Archives asked Mr. Trump as early as May 2021 for files that needed to be returned. In January, the agency was able to collect 15 boxes of documents. The affidavit included a letter from May 2022 showing that Trump’s lawyers knew that he might be in possession of classified materials and that the Justice Department was investigating the matter.

Takeaways From the Affidavit Used in the Mar-a-Lago Search

The material included highly classified documents. The F.B.I. said it had examined the 15 boxes Mr. Trump had returned to the National Archives in January and that all but one of them contained documents that were marked classified. The markings suggested that some documents could compromise human intelligence sources and that others were related to foreign intercepts collected under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

Takeaways From the Affidavit Used in the Mar-a-Lago Search

Prosecutors are concerned about obstruction and witness intimidation. To obtain the search warrant, the Justice Department had to lay out possible crimes to a judge, and obstruction of justice was among them. In a supporting document, the Justice Department said it had “well-founded concerns that steps may be taken to frustrate or otherwise interfere with this investigation if facts in the affidavit were prematurely disclosed.”

The judge’s action came a day after the Justice Department released a redacted version of the warrant affidavit. A different federal judge, Bruce E. Reinhart, a magistrate judge in West Palm Beach, had ordered the unsealing of the document, albeit with large portions blacked out.

The affidavit said, among other things, that the Justice Department wanted to search Mar-a-Lago to ensure the return of highly classified documents that Mr. Trump had removed from the White House, including some that department officials believed could jeopardize “clandestine human sources” who worked undercover gathering intelligence.

Special masters are not uncommon in criminal investigations that include the seizure by the government of disputed materials that could be protected by attorney-client privilege. A special master was appointed, for example, after the F.B.I. raided the office of Mr. Trump’s longtime personal lawyer Michael D. Cohen in 2018 and took away evidence that Mr. Cohen and Mr. Trump claimed should have been kept from investigators because of the nature of their professional relationship.

In the case of the search of Mar-a-Lago, Mr. Trump’s lawyers have argued that some of the documents taken by the F.B.I. could be shielded not by attorney-client privilege, but rather by executive privilege, a vestige of Mr. Trump’s service as president. But legal scholars — and some judges — have expressed skepticism that former presidents can unilaterally assert executive privilege over materials related to their time in office once they leave the White House.

In December, for example, a federal appeals court in Washington ruled that, despite his attempts to invoke executive privilege, Mr. Trump had to turn over White House records related to the attack on the Capitol to the House committee investigating the Jan. 6 riot.

In her notice of intent, Judge Cannon gave the Justice Department until Tuesday to file a response to Mr. Trump’s request. The judge also instructed prosecutors to send her under seal “a more detailed receipt” specifying the items that were seized by federal agents during the search of Mar-a-Lago on Aug. 8. As part of their initial request, Mr. Trump’s lawyers had asked for a complete inventory of what was taken, arguing that the receipt the F.B.I. had given them was insufficient.

Source: nytimes.com