Once a rising star of the Democratic Party, he served 13 months in prison for bribery after being targeted in an F.B.I. scam involving a phony sheikh.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

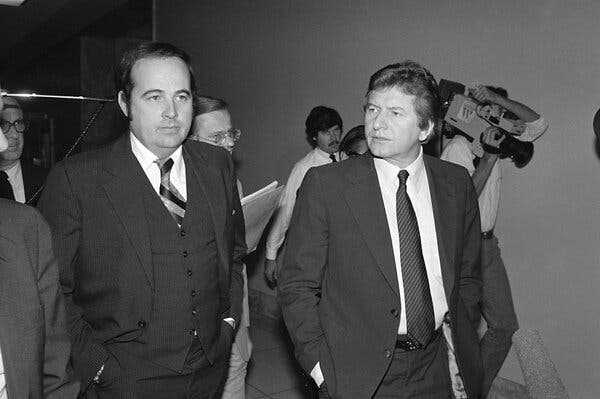

Representative John Jenrette Jr., right, with his lawyer, Kenneth Robinson, outside the House Ethics Committee room in Washington in December 1980. He resigned from the House that month, after being convicted on bribery charges and losing re-election, rather than be expelled.

John Jenrette Jr., a charismatic Democratic Representative from South Carolina who became ensnared in the Abscam investigation of political corruption that also brought down six other members of Congress, died on Friday in Conway, S.C. He was 86.

His death was announced by the Goldfinch Funeral Home. It did not cite a cause.

Mr. Jenrette was in his third term in the House and had a progressive record and a strong reputation for serving his constituents, especially Black citizens, when his political career was ruined by his involvement in Abscam — a two-year sting operation that videotaped politicians and others taking bribes from federal agents pretending to be rich Arabs looking for favors.

A former social acquaintance, John Stowe, got in contact with Mr. Jenrette in 1979, saying that he had found a wealthy investor, sometimes referred to as a sheikh — an invention of the F.B.I. — who was willing to finance the revival of an empty munitions factory, bringing 400 jobs to Mr. Jenrette’s district. To sweeten the deal, Mr. Stowe said, he needed legislation that would let the sheikh emigrate to the United States.

Mr. Jenrette was captured on videotape, during one of his visits to a townhouse in the Georgetown section of Washington in December 1979, discussing a payment he would accept with people said to be lieutenants of the phony sheikh.

To an offer of $100,000, with $50,000 up front, Mr. Jenrette said, ”I have larceny in my blood — I’d take it in a goddamn minute.”

Five envelopes, each containing $10,000, were laid out on a desk.

Despite the urgings of Anthony Amoroso, an F.B.I. agent posing as one of the sheikh’s executives, Mr. Jenrette didn’t take the money. Instead, two days later, Mr. Stowe picked it up. Mr. Jenrette, fearful of appearing to have accepted a direct payoff to help the sheikh, agreed to receive $10,000 from Mr. Stowe as a loan, and received a promissory note for it.

The jury delivered a quick verdict, convicting Mr. Jenrette and Mr. Stowe of one count of conspiracy and two counts of violating the federal anti-bribery statute by promising to introduce legislation to let a fictitious Arab businessman into the United States.

Mr. Jenrette said he believed the conviction was based on the incriminating videotapes of the two men that were shown during the trial.

“Obviously, the videos were all they considered,” he said of the jurors. “I pray that they were not out to get a congressman.” He added, “I can look at my two beautiful children and my gorgeous wife and say, regardless of what those tape say, that I didn’t take any money.”

The case put a great strain on his marriage, which had already been roiled by his womanizing. His wife, Rita (Carpenter) Jenrette soon wrote, with a co-author, an article for The Washington Post with the headline “Diary of a Mad Congresswife,” in which she declared, “I hate my life as a congressional wife” and described Mr. Jenrette’s struggles with alcohol.

A few months later, she posed for Playboy and, in an accompanying article, said that she and her husband had once made love on the steps of the United States Capitol. When she was profiled in 2017 on “CBS Sunday Morning,” she amended that to say that they had simply shared a passionate kiss behind a Capitol column.

The Jenrettes divorced in 1981 after five years of marriage.

In a What’sApp interview with The New York Times on Tuesday, Ms. Jenrette said that her ex-husband’s alcoholism had fueled his participation in the sting. But he also needed money. He was paying substantial alimony to his first wife, Sally (Jordan) Jenrette, as well as child support payments, and he was involved in a money-losing resort development.

“Between our two salaries we were OK but not flush with money,” Ms. Jenrette, now known as Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, wrote from Italy. “This evoked his childhood to him, the poverty, the lack, the uncertainty brought to a child with elderly parents. He drank more, and the rest is history.”

She said she had forced him to go to five rehab centers during their brief marriage.

“He’d be OK for while,” she said in an earlier phone interview, “but it’s hard to overcome it.”

ImageMr. Jenrette with his wife, Rita, in 1976, shortly after they married. Their marriage was troubled and ended after five years.Credit…Associated Press

Mr. Jenrette continued campaigning for a fourth term through his indictment and trial. But a month after his conviction on Oct. 7, 1980, he lost his seat to his Republican opponent, John Napier by 5,190 votes. In December, he resigned his House seat rather than be expelled.

After unsuccessfully appealing his conviction, based in part on the claim that he had been a victim of entrapment, he was sentenced to two years in federal prison.

He was released in 1986 after serving 13 months.

In addition to Mr. Jenrette, Abscam snared a senator, Harrison A. Williams of New Jersey; five other congressmen,; and other public officials, including the mayor of Camden, N.J.

The sting inspired the 2013 movie “American Hustle,” which starred Christian Bale as the operation’s central figure, a con artist based on the real-life Mel Weinberg, a convicted swindler who was a key player in Abscam and portrayed one of the sheikh’s lieutenants who met with Mr. Jenrette. Mr. Jenrette was not a character in the film.

John Wilson Jenrette Jr. was born on May 19, 1936, in Conway, S.C. His father was a farmer and a carpenter who repaired local train stations. His mother, Mary (Herring) Jenrette, sold baked goods and eggs from chickens she raised. The family was poor. John often did not have shoes to wear.

“His family didn’t have a vehicle,” John Clark, a former aide to Mr. Jenrette and the author, with Cookie Miller VanSice, of “Capitol Steps and Missteps: The Wild, Improbable Ride of Congressman John Jenrette” (2017), said in a phone interview. “They had a wagon hitched to a mule. He joked that his house had two bedrooms and a path to an outhouse.”

After graduating from Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C., in 1958 with a bachelor’s degree in political science, Mr. Jenrette earned his law degree at the University of South Carolina School of Law in Columbia in 1962. He served in the South Carolina House of Representatives from 1965 until 1972, when he made an unsuccessful run for a seat in the United States House.

But he won the seat in 1974 and was re-elected twice, the third time without any Republican opposition. He was the majority whip of his freshman class and moved further in the House leadership when he was named the deputy majority whip, under Representative John Brademas of Indiana, in 1977.

Any further ascension into House leadership, however, ended with Abscam.

In the decades after his release from federal prison, Mr. Jenrette worked in various businesses, including real estate development. But he got into further legal trouble in 1989, when he was convicted of stealing a pair of shoes and a tie and altering the price tags on a shirt and a pair of pants at a department store in Fairfax, Va.

He served 20 days in jail and was sentenced to 200 hours of community service.

“I’ve done volunteer work all my life, but this is the first time it’s got so much publicity,” he told reporters during his first day of community service at the Horry County, S.C., public defender’s office.

His survivors include his wife, Rosemary (Long) Jenrette.

Source: nytimes.com