The system, in which voters list candidates in order of preference, is gaining popularity around the nation. Nevada will vote whether to adopt it.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this articleGive this articleGive this article

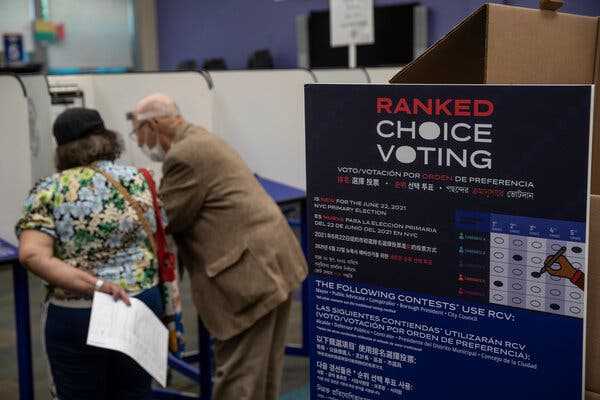

New Yorkers used ranked-choice voting for the first time in a mayoral election last year.

Ranked-choice voting, when voters list candidates in order of preference instead of casting a single ballot, has the potential this election season to continue disrupting the influence of the dual-party system in the United States.

Commonly used by cities — including New York City, for its 2021 Democratic primary for mayor — ranked-choice voting is gaining popularity around the United States as a statewide option. This year, Nevada is deciding at the polls whether to join Maine and Alaska, which adopted ranked-choice in 2021, in using it to conduct future elections.

The benefits of ranked-choice, which is sometimes called instant-runoff voting because people vote only once, are plentiful, proponents say.

By giving voters more selections, ranked-choice aims to diminish the likelihood of voting along party lines, reducing polarization. If voters recognize that their vote would go toward their next choice if their preferred candidate is eliminated, the system ultimately produces a winner who satisfies more of the electorate. And because it removes the binary choice of voting for only one candidate, ranked-choice incentivizes candidates to build broader backing so they could appeal to their rivals’ supporters.

Critics, meantime, point to ranked-choice’s relative unfamiliarity, with experts suggesting that overhauling a voting system can lead to negative consequences like lower turnout, voter confusion or a spike in invalidated ballots.

The State of the 2022 Midterm Elections

Election Day is Tuesday, Nov. 8.

- Final Landscape: As candidates make their closing arguments, Democrats are bracing for potential losses even in traditionally blue corners of the country as Republicans predict a red wave.

- The Battle for Congress: With so many races on edge, a range of outcomes is still possible. Nate Cohn, The Times’s chief political analyst, breaks down four possible scenarios.

- Voting Worries: Even as voting goes smoothly, fear and suspicion hang over the process, exposing the toll former President Donald J. Trump’s falsehoods have taken on American democracy.

Although the mechanics of ranked-choice are nominally the same, states have employed it in different ways.

For example, Alaska in August unveiled a new electoral system approved in a 2020 ballot initiative, which opened primaries to all voters, regardless of their affiliation. Under those rules, voters could choose one candidate, and the four who drew the most votes moved on to compete in a runoff of sorts in the general election, in which voters rank their choices. The preferences are counted until someone secures a majority.

In the initial stage of that experiment, ranked-choice helped Mary Peltola, a Democrat, defeat former Gov. Sarah Palin, her Republican opponent, in a special House election simply because voters had options: Even though more voters at first picked a Republican candidate, many Republican voters, when given a second choice, preferred a Democrat — Ms. Peltola — over Ms. Palin.

Ms. Peltola, who became the first Alaska Native in Congress, is seated only until the term of Representative Don Young — who died unexpectedly in March — ends in January. She will vie with Ms. Palin; another Republican challenger, Nick Begich III; and Chris Bye, a libertarian in a ranked-choice election Tuesday for a full term.

Alaska will also rank candidates for Senate, governor and the state legislature.

In Nevada, voters will determine whether to adopt an electoral system similar to Alaska’s.

Under a proposed constitutional amendment, all registered voters will be permitted to participate in primaries for statewide and federal offices — though not for president — with the top five candidates advancing to the general election. The law currently requires voters to be registered as Democrats or Republicans in order to participate in their parties’ primaries.

During the general election, voters would then list candidates in order of preference. If no candidate receives a majority, the last-place finisher would then be eliminated and his or her supporters’ votes would be reallocated to their second choices until one candidate has at least 50 percent of the votes.

If approved on Tuesday, the measure would be placed on the ballot again in 2024 for voters to decide. The earliest that the changes could take effect would be in 2025.

Source: nytimes.com