The Biden administration recently secured the release of two Americans convicted of criminal charges in Russia, but even fabricated charges of spying can raise the stakes.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

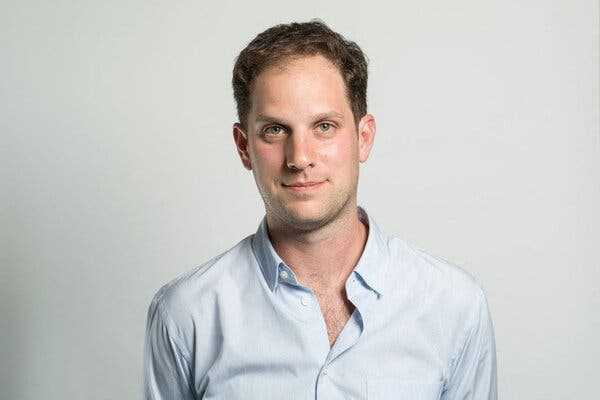

Evan Gershkovich, a Wall Street Journal reporter, is accused by Russia of trying to gain illicit information about the country’s “military-industrial complex.”

WASHINGTON — Freeing any American who has been imprisoned in Russia is a daunting challenge, but the espionage charge leveled against a Wall Street Journal reporter detained there this week will make efforts to secure his release particularly difficult.

The Russian authorities have accused the reporter, Evan Gershkovich, of trying to gain illicit information about the country’s “military-industrial complex.” In the Kremlin’s eyes, experts say, that puts him in a special category of prisoners — one quite different from that of two Americans whom Russia has released since the start of the war in Ukraine.

Both of those Americans, the W.N.B.A. star Brittney Griner and the former U.S. Marine Trevor Reed, were being held on standard criminal offenses — Ms. Griner on drug charges, Mr. Reed on charges of assaulting police officers — when the Biden administration negotiated their releases, trading them for Russians who were serving criminal sentences of their own in American prisons.

“Let him go,” President Biden told reporters on Friday when asked what his message about Mr. Gershkovich was for the Kremlin.

But the allegations against Mr. Gershkovich, which he denied in a court appearance on Thursday and which his employer adamantly rejects, could signal a higher Kremlin asking price than in those earlier cases.

That is the lesson to date in the case of yet another American accused of spying and imprisoned by Russia, Paul Whelan. The corporate security executive and former Marine was arrested at a Moscow hotel in December 2018, charged with espionage, and given a 16-year prison sentence. Mr. Whelan has denied the charges against him, and U.S. officials insist that he was not conducting espionage — a claim supported by intelligence experts who do not find the notion credible.

People familiar with Mr. Whelan’s case say that Russia has insisted on what would amount to a fair trade if the charges against him were legitimate — a spy for a spy, in other words. Russia officials “continue to insist on sham charges of espionage,” Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken said in December, “and are treating Paul’s case differently.”

That helps explain why Mr. Whelan has remained in a bleak Russian prison months after Mr. Reed and Ms. Griner returned home. The United States is not known to be detaining a Russian spy, and even if it were, the Biden administration would be reluctant to make a purported spy trade that lent credibility to false Kremlin allegations of espionage.

U.S. officials say Russia has demanded to trade Mr. Whelan for Vadim Krasikov, a Russian assassin serving a life sentence in Germany for murdering a Chechen fighter in a Berlin park. The United States says it cannot make a bargain involving a prisoner held in Germany.

Clear signs have already emerged that the Kremlin was motivated by a potential spy swap. Pro-Russia commentators started speculating about the possibility almost immediately, even as they posited that Mr. Gershkovich would first need to be tried and sentenced.

Speaking on a state television talk show Thursday, one commentator, Igor Korotchenko, said the Biden administration needed to “accept the situation” and “work on thinking through possible trades that could happen after this U.S. citizen gets his sentence.”

Daniel Hoffman, a former C.I.A. operative who was stationed in Moscow for five years, called the arrest a cynical ploy by President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia.

“Putin essentially takes American citizens hostage because he wants to use them as leverage,” Mr. Hoffman said. “The charges he brings are just going to reflect how he sees the endgame. So if he brings espionage charges, he’s going to want to get one of his own spies back.”

Mr. Hoffman said Mr. Putin could be seeking the release of Sergey Cherkasov, a man who U.S. officials say is a Russian undercover operative who posed as a Brazilian student to study in the United States before getting a job at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. Mr. Cherkasov was deported last April from the Netherlands to Brazil, where he was arrested, prosecuted and sentenced to 15 years in prison. But it was only last week that the U.S. Justice Department charged Mr. Cherkasov as a Russian intelligence agent, leading Mr. Hoffman and others to think Mr. Putin might have been motivated to respond.

Several accused Russian agents have been arrested by Western nations in recent months, including six people detained by Polish authorities in mid-March and accused of planning sabotage operations, and a couple sentenced to prison by a Swedish court in January for a decade of spying for Moscow. But U.S. officials have said that, as in the case of Mr. Krasikov, they cannot instruct allies to release prisoners for America’s benefit.

For the Kremlin, the arrest of Mr. Gershkovich serves other purposes. It is also a chance to show that Russia is prepared to take ever more drastic steps in confronting what Mr. Putin frequently refers to as “Western hegemony.”

At the same time, the Kremlin’s propaganda machine has used the case to press its narrative of Western subversion. An evening news broadcast on state television referred to Mr. Gershkovich as “the wolf of Wall Street,” and asserted that he had been spreading “anti-Russian, pro-Ukrainian propaganda” in his articles.

Just days before Mr. Gershkovich’s arrest, he wrote an article on the toll that Western sanctions against Russia have begun to take on the country’s economy.

“This is a dark day for journalism and for information about what’s happening in Russia,” said Fiona Hill, a former National Security Council official for Russia matters in the Trump White House.

Mr. Gershkovich would face up to 20 years in prison if convicted. Acquittals in espionage cases in Russia are virtually unheard-of.

If recent precedent is a guide, he is likely to spend more than a year in a high-security prison in almost complete isolation awaiting the end of a lengthy investigation and trial, according to two Russian lawyers who have worked on similar cases.

A Moscow court on Thursday ordered Mr. Gershkovich jailed until May 29. But according to Ivan Pavlov, a Russian lawyer who has defended Russian clients in espionage and treason cases, the proceedings might take up to two years.

During that time, details of the case will most likely be shrouded from the public, he said.

Russia’s state media reported that after he was detained in Yekaterinburg, a city in the Ural Mountains, Mr. Gershkovich was transferred to Moscow’s infamous Lefortovo prison, once used by the K.G.B. to hold Soviet dissidents.

ImageMr. Gershkovich was transferred to Moscow’s Lefortovo prison after being detained in Yekaterinburg.Credit…Evgenia Novozhenina/Reuters

Ms. Griner was freed in December in a trade for the notorious Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout, who was serving a U.S. federal prison sentence for aiding terrorists. Mr. Reed was traded last April for a Russian pilot convicted of drug smuggling charges. U.S. officials have reported no recent progress in their efforts to win Mr. Whelan’s freedom.

On Thursday, a Russian deputy foreign minister, Sergei A. Ryabkov, said it was too soon to discuss a swap for Mr. Gershkovich. According to the Russian news agency Interfax, he noted that recent exchanges had occurred only after the accused had been convicted.

Source: nytimes.com