The American contractor L3 Harris is said to have cited support from intelligence officials for its effort to acquire NSO, the Israeli spyware company blacklisted by the Biden administration.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

- Read in app

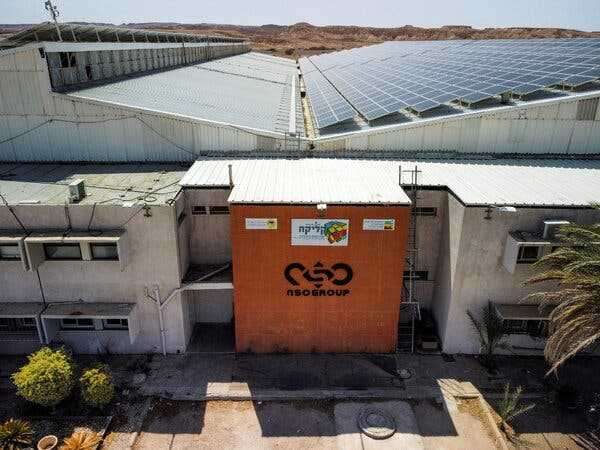

An NSO office in southern Israel. The Biden administration blacklisted the cyber hacking firm, saying it had acted “contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.”

A team of executives from an American military contractor quietly visited Israel numerous times in recent months to try to carry out a bold but risky plan: purchasing NSO Group, the cyber hacking firm that is as notorious as it is technologically accomplished.

The impediments were substantial for the team from the American company, L3Harris, which also had experience with spyware technology. They started with the uncomfortable fact that the United States government had put NSO on a blacklist just months earlier because the Israeli firm’s spyware, called Pegasus, had been used by other governments to penetrate the phones of political leaders, human rights activists and journalists.

Pegasus is a “zero-click” hacking tool that can remotely extract everything from a target’s mobile phone, including messages, contacts, photos and videos without the user having to click on a phishing link to give it remote access. It can also turn the mobile phone into a tracking and recording device.

NSO had acted “contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States,” the Biden administration said in announcing the blacklisting in November, barring American companies from doing any business with the Israeli firm.

But five people familiar with the negotiations said that the L3Harris team had brought with them a surprising message that made a deal seem possible. American intelligence officials, they said, quietly supported its plans to purchase NSO, whose technology over the years has been of intense interest to many intelligence and law enforcement agencies around the world, including the F.B.I. and the C.I.A.

The talks continued in secret until last month, when word of NSO’s possible sale leaked and sent all the parties scrambling. White House officials said they were outraged to learn about the negotiations, and that any attempt by American defense firms to purchase a blacklisted company would be met by serious resistance.

Days later, L3Harris, which is heavily reliant on government contracts, notified the Biden administration that it had scuttled its plans to purchase NSO, according to three United States government officials, although several people familiar with the talks said there have been attempts to resuscitate the negotiations.

Left in place are questions in Washington, other allied capitals and Jerusalem about whether parts of the U.S. government — with or without the knowledge of the White House — had seized an opportunity to try to bring control of NSO’s powerful spyware under U.S. authority, despite the administration’s very public stance against the Israeli firm.

It also left unsettled the fate of NSO, whose technology has been a tool of Israeli foreign policy even as the firm has become a target of intense criticism for the ways its spyware is used by governments against their citizens.

The episode was the latest skirmish in an ongoing battle among nations to gain control of some of the world’s most powerful cyberweapons, and it reveals some of the headwinds faced by a coalition of nations — including the United States under the Biden administration — as it tries to rein in a lucrative global market for sophisticated commercial spyware.

Spokesmen for L3Harris and NSO declined to comment about the negotiations between the companies. A spokeswoman for Avril Haines, the director of national intelligence, declined to comment on whether any American intelligence officials quietly blessed the discussions. A spokesman for the Commerce Department declined to give specifics about any discussions with L3 Harris about purchasing NSO.

A spokesman for the Israeli defense ministry declined to comment, as did a spokeswoman for the Israeli prime minister.

The Biden administration’s decision to put NSO on a Commerce Department blacklist came after years of revelations about how governments had used Pegasus, NSO’s premier hacking tool, as an instrument of domestic surveillance. But the United States itself has also purchased, tested and deployed Pegasus.

In January, The New York Times revealed that the F.B.I. had purchased Pegasus software in 2019, and that government lawyers at the F.B.I. and the Justice Department had debated whether to deploy the spyware for use in domestic law enforcement investigations. The Times also reported that in 2018 the C.I.A. had purchased Pegasus for the government of Djibouti to conduct counterterrorism operations, despite that country’s record of torturing political opposition figures and imprisoning journalists.

A decision by L3 to terminate the acquisition talks would leave NSO’s future in doubt. The company had seen a deal with the American defense contractor as a potential lifeline after being blacklisted by the Commerce Department, which has crippled its business. American firms are not allowed to do business with companies on the blacklist, under penalty of sanctions.

As a result, NSO cannot buy any American technology to sustain its operations — whether it be Dell servers or Amazon cloud storage — and the Israeli firm has been hoping that being sold to a company in the United States could lead to the sanctions being lifted.

For more than a decade, Israel has treated NSO as a de facto arm of the state, granting licenses for Pegasus to numerous countries — including Saudi Arabia, Hungary and India — with which the Israeli government hoped to nurture stronger security and diplomatic ties.

But Israel has also denied Pegasus to countries for reasons of diplomacy. Last year, Israel rejected a request by the government of Ukraine to purchase Pegasus to use against targets in Russia, fearing that the sale would damage Israel’s relations with the Kremlin.

The Israeli government also makes extensive use of Pegasus and other locally made cyber tools for its own intelligence and law enforcement purposes, giving it further incentive to find a way for NSO to survive the American sanctions.

During the discussions about the possible sale of NSO to L3 Harris — which included at least one meeting with Amir Eshel, the director general of the Israeli defense ministry, who would have to approve any deal — the L3Harris representatives said they had received permission from the United States government to negotiate with NSO, despite the company’s presence on the American blacklist.

L3 Harris’s representatives told the Israelis that U.S. intelligence agencies supported the acquisition as long as certain conditions were met, according to five people familiar with the discussions.

One of the conditions, those people said, was that NSO’s arsenal of “zero days” — the vulnerabilities in computer source code that allow Pegasus to hack into mobile phones — could be sold to all of the United States’ partners in the so-called Five Eyes intelligence sharing relationship. The other partners are Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. A senior British diplomat declined to comment on questions about the degree of knowledge British intelligence had about a possible deal between L3 and NSO.

Such a plan would have been highly unusual had it been finalized, since the Five Eyes countries usually only purchase intelligence products that have been developed and manufactured within those countries.

Israeli defense ministry officials were open to this arrangement. But following heavy pressure from the Israeli intelligence community, it balked at another request: that the Israeli government allow NSO to share the computer source code for Pegasus — which allows it to exploit the vulnerabilities in the phones it targets — with the Five Eyes countries. They also did not agree, at least not in the first phase, to allow L3’s cyber experts to come to Israel and join NSO’s development teams at the company’s headquarters north of Tel Aviv.

Representatives of the defense ministry also insisted that Israel retain its authority to grant export licenses for NSO’s products, but said they were willing to negotiate over which countries received the spyware.

Over the course of the discussions, there were numerous issues that would have required the approval of the United States government. L3Harris representatives said that they had discussed the issues with American officials, who had agreed in principle, according to the people familiar with the discussions.

To help negotiate the sale of NSO, L3Harris hired an influential lawyer in Israel with deep ties to Israel’s defense establishment. The lawyer, Daniel Reisner, is the former head of the International Law Department at the Israeli Military Prosecutor’s Office and acted as a special adviser on the Middle East peace process to former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

In the months since the Biden administration announced the blacklist in November, and as the Israeli government pressed for a way to keep NSO from going under, the Commerce Department in Washington sent a list of questions to NSO and another Israeli hacking firm that had been blacklisted at the same time, about how the spyware works, who it targets and whether the company has any control over how its nation-state clients deploy the hacking tools.

The list, reviewed by The Times, asked whether NSO maintained “positive control over its products” and whether Americans overseas were protected from having NSO’s products deployed against them.

Another asked if NSO would “shut down access to its products if the U.S. government informs them that there is an unacceptable risk of the tool being used for human rights abuses by a particular customer?”

Separately from the proposed NSO and L3 Harris deal, Israeli officials negotiated unsuccessfully with the Commerce Department about getting NSO removed from the American blacklist in advance of President Biden’s trip to Israel in the coming week.

News last month of L3Harris’s talks to purchase NSO seemed to blindside White House officials. After the website Intelligence Online reported on the possible sale, a top White House official said such a transaction would pose “serious counterintelligence and security concerns for the U.S. government” and that the administration would work to ensure that the deal did not happen.

The official said that an American company, particularly a defense contractor, should have been aware that any transaction “would spur intensive review to examine whether the transaction process poses a counterintelligence threat to the U.S., government and its systems and information.”

Last week, in response to questions from The Times, another U.S. official said “after learning about the potential sale, the IC did an analysis that raised concerns about the sale’s implications and informed the administration’s position.”

While not a household defense industry name like Lockheed Martin or Raytheon, L3Harris earns billions each year from American government contracts at both the federal and state level. According to the company’s most recent annual report, more than 70 percent of the company’s revenue in fiscal year 2021 came from various U.S. government contracts.

USAspending.gov, a website that tracks government contracts, indicates that the Defense Department is L3Harris’ biggest government client.

The company once produced a surveillance system called Stingray that was used by the F.B.I. and local American police forces until the company discontinued production. In 2018, the company purchased Azimuth Security and Linchpin Labs, two Australian cyber firms that Vice reported had sold zero day exploits to the Five Eyes countries.

In 2016, the F.B.I. enlisted Azimuth to help break into the Apple phone of a terrorist who had carried out a deadly shooting in San Bernardino, Calif., killing more than a dozen people, according to a report in the Washington Post.

Azimuth’s work for the F.B.I. ended a standoff between the bureau and Apple, which had pointedly refused to help the F.B.I. unlock the phone in the San Bernardino case. The tech giant argued it had no backdoor to allow the F.B.I. access to the phone, and were loathe to create one because it would weaken the iPhone’s security features it promotes to its customers.

Susan C. Beachy contributed research.

Source: nytimes.com