The movie about the daring mission to rescue American diplomats from Tehran portrayed a single C.I.A. officer sneaking into the Iranian capital. In reality, the agency sent two officers.

- Share full article

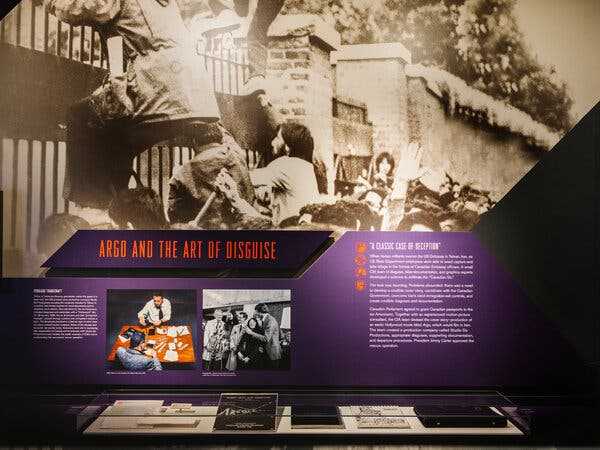

An exhibit about the Argo operation is on display at the museum in the C.I.A.’s headquarters in Langley, Va.

In the midst of the 1979 Iran hostage crisis, the C.I.A. began what came to be noted as one of the spy agency’s most successful publicly known operations: the rescue of six American diplomats who had escaped the overrun U.S. Embassy — using a fake movie as the cover story.

“Argo,” the real-life 2012 movie about the C.I.A.’s fake movie, portrayed a single C.I.A. officer, Tony Mendez, played by Ben Affleck, sneaking into Tehran to rescue the American diplomats in a daring operation.

But in reality, the agency sent two officers into Tehran. For the first time on Thursday, the C.I.A. is releasing the identity of that second officer, Ed Johnson, in the season finale of its new podcast, “The Langley Files.”

Mr. Johnson, a linguist, accompanied Mr. Mendez, a master of disguise and forgery, on the flight to Tehran to cajole the diplomats into adopting the cover story, that they were Canadians who were part of a crew scouting locations for a science fiction movie called “Argo.” The two then helped the diplomats with forged documents and escorted them through Iranian airport security to fly them home.

Although Mr. Johnson’s name was classified, the C.I.A. had acknowledged a second officer had been involved. Mr. Mendez, who died in 2019, wrote about being accompanied by a second officer in his first book, but used a pseudonym, Julio. A painting that depicts a scene from the operation and hangs in the C.I.A.’s Langley, Va., headquarters, shows a second officer sitting across from Mr. Mendez in Tehran as they forge stamps in Canadian passports. But the second officer’s identity is obscured, his back turned to the viewer.

ImageEd Johnson, right, receiving the C.I.A.’s Intelligence Star from John N. McMahon, the agency’s deputy director for operations at the time, in a photo provided by Mr. Johnson’s family. Mr. Johnson was the long-unidentified second C.I.A. officer in the rescue of six American diplomats from Tehran.

The agency began publicly talking about its role in rescuing the diplomats 26 years ago. On the agency’s 50th anniversary, in 1997, the C.I.A. declassified the operation, and allowed Mr. Mendez to tell his story, hoping to balance accounts of some of the agency’s ill-fated operations around the world with one that was a clear success.

But until recently, Mr. Johnson preferred that his identity remain secret.

“He was someone who spent his whole life doing things quietly and in the shadows, without any expectation of praise or public recognition,” said Walter Trosin, a C.I.A. spokesman and co-host of the agency’s podcast. “And he was very much happy to keep it that way. But it was his family that encouraged him, later in life, to tell his side of the story because they felt there would be value to the world in hearing it.”

After Mr. Trosin heard Mr. Johnson and his family were visiting C.I.A. headquarters early this summer, he arranged to meet them. At the meeting, Mr. Trosin and his podcast co-host saw how much the C.I.A.’s recognition of Mr. Johnson’s work meant to his family and started looking for a way to tell the story on the podcast.

Mr. Johnson, 80, was unavailable to discuss his career on the podcast or with The New York Times because of health issues. Undeterred, Mr. Trosin dived into the agency’s classified archives.

Soon after dangerous operations, the C.I.A. often records secret interviews with the participants, to capture so-called lessons learned for its own, classified histories. In addition, for many storied officers, the C.I.A. records classified oral histories at the end of their careers. C.I.A. historians had done one such oral history with Mr. Johnson.

“We found out there was this prior interview,” Mr. Trosin said. “And at least portions of which could be made public.”

Thanks to the “Argo” movie, the C.I.A.’s role in the rescue of the diplomats, who were being sheltered by the Canadians, has become one of the agency’s best-known operations.

The C.I.A. museum, which has a tendency to dwell on the agency’s failures, features a display on the operation. Among the artifacts is a copy of the script — or at least treatment — of the fake movie complete with the Hollywood-esque tagline “A Cosmic Conflagration.” Also displayed are the business cards of the fake production company used as part of the cover story and the concept art for the movie, which featured drawings from Jack Kirby, the celebrated comic book artist who helped create the Marvel universe.

Like the painting, the museum display did not identify Mr. Johnson.

ImageA painting depicting a scene from the operation hanging in the C.I.A.’s headquarters shows a second officer sitting across from Tony Mendez as they forge stamps in Canadian passports while in Tehran but does not show his face.Credit…Jason Andrew for The New York Times

But C.I.A. officials said Mr. Johnson, an expert in languages and extracting people from tricky places, was invaluable to the operation.

At the time of the hostage crisis, Mr. Johnson was based in Europe, focusing his Cold War work on learning how to get in and out of countries that were not always hospitable to Americans.

When Iranian revolutionaries overran the American Embassy and took 52 diplomats hostage, six Americans working in the consular office escaped. They eventually ended up under the protection of Kenneth D. Taylor, Canada’s ambassador to Iran, and the C.I.A. began working on a plan to sneak them out of the country.

Mr. Mendez, who had worked with Hollywood experts to hone his tradecraft, came up with the plan to use a fake movie, which he named “Argo” after the story of Jason and the Argonauts, the ancient Greek heroes who had undertaken the arduous mission to retrieve the Golden Fleece.

While some C.I.A. extraction operations at the time used single officers, the agency decided that for the rescue of the six diplomats, two officers would be needed, said Brent Geary, a C.I.A. historian who has studied the agency’s history in Iran.

Mr. Johnson was fluent in French, German, Spanish and Arabic. He did not, however, speak Persian, the predominant language in Iran.

Dr. Geary said the agency had Persian speakers, but could not risk sending in someone who might be known to current or former Iranian officials. The belief was also that someone fluent in the local language could draw questions, and what was critical to the mission was having people with Mr. Mendez’s and Mr. Johnson’s skill sets.

“They had trained to get in and out of tight spots,” Dr. Geary said.

Even without Persian, Mr. Johnson’s languages came into use. Soon after arriving, Mr. Mendez and Mr. Johnson mistakenly ended up at the Swedish Embassy, across the street from the U.S. Embassy, which was occupied by the Iranian revolutionaries.

ImageTony Mendez, a master of disguise and forgery, was played by Ben Affleck in “Argo.”Credit…Mark Makela/Corbis, via Getty Images

Outside the embassy, Mr. Johnson discovered that both he and the Iranian guard spoke German, and the two began talking. The guard then hailed a taxi and wrote the address of the Canadian Embassy on a piece of paper and sent the two fake movie producers off.

“I have to thank the Iranians for being the beacon who got us to the right place,” Mr. Johnson said in his oral history.

In the “Argo” movie, Mr. Affleck, portraying Mr. Mendez, is shown swiping Iranian forms that were needed to enter and exit the country. But in reality, it was Mr. Johnson who performed the sleight of hand to steal the documents. (Mr. Affleck did not respond to a request to comment.)

In his oral history, Mr. Johnson said the “biggest thing” was to persuade the diplomats that they could pull off the movie team cover story.

“These are rookies,” Mr. Johnson recalled in the recorded session. “They were people who were not trained to lie to authorities. They weren’t trained to be clandestine, elusive.”

But Mr. Johnson recounted that the six diplomats pulled it off, putting aside their nervousness and adopting the persona of a happy-go-lucky film crew.

The climax of the real movie — spoiler alert for a film that has been out for more than a decade — involves Iranian government officials reacting skeptically to the cover story, then realizing the “film crew” were American diplomats and chasing the plane down the runway. None of which happened.

In reality, there was simply one last security check as the group left the departure lounge.

“A couple of young Iranians, they’re patting people down as they went through,” Mr. Johnson recalled, noting that the diplomats were leaning into their parts, cracking jokes as they approached the checkpoint.

With that, the diplomats, Mr. Mendez and Mr. Johnson were through the last checks. In the oral history, Mr. Johnson recalled boarding and seeing the plane’s name painted on the side. It was named Aargau, and Mr. Johnson thought to himself, “What the hell?”

“After a bit, I forget when, I picked up The Herald Tribune and did the crossword puzzle,” Mr. Johnson said. “And one of the one of the clues was Jason’s companions … Jason and the Argonauts.”

In the C.I.A. podcast, Mr. Trosin said the name of the plane and the crossword were simply coincidences.

“To be clear,” Mr. Trosin said, “this is not C.I.A. officers with excess free time just planting clues.”

Julian E. Barnes is a national security reporter based in Washington, covering the intelligence agencies. Before joining The Times in 2018, he wrote about security matters for The Wall Street Journal. More about Julian E. Barnes

- Share full article

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Source: nytimes.com