The changes outlined by the senators are intended to prevent a repeat of the effort on Jan. 6, 2021, to overturn the presidential election in Congress.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

- 50

- Read in app

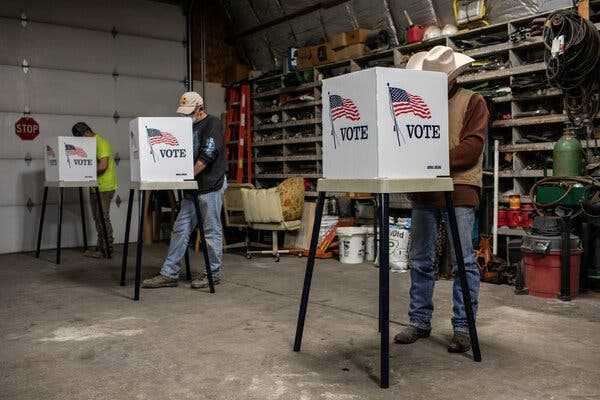

Voters in Story County, Iowa, in 2020. The new legislation focuses mainly on the handling of electoral votes and does not incorporate wider voting protections.

WASHINGTON — A bipartisan group of senators proposed new legislation on Wednesday to modernize the 135-year-old Electoral Count Act, working to overhaul a law that President Donald J. Trump tried to abuse on Jan. 6, 2021, to interfere with Congress’s certification of his election defeat.

The legislation aims to guarantee a peaceful transition from one president to the next, after the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol demonstrated how the current law could be manipulated to disrupt the process. One measure would make it more difficult for lawmakers to challenge a state’s electoral votes when Congress meets to make its official count. It would also clarify that the vice president has no discretion over the results and set out the steps to begin a presidential transition.

A second bill would increase penalties for threats and intimidation of election officials and encourage steps to improve the handling of mail-in ballots by the Postal Service.

Alarmed at the events of Jan. 6 that showed longstanding flaws in the law governing the electoral count process, a bipartisan group of lawmakers led by Senators Susan Collins, Republican of Maine, and Joe Manchin III, Democrat of West Virginia, has been meeting for months to try to agree on a rewrite.

“From the beginning, our bipartisan group has shared a vision of drafting legislation to fix the flaws of the archaic and ambiguous Electoral Count Act of 1887,” 16 senators said in a joint statement. “Through numerous meetings and debates among our colleagues as well as conversations with a wide variety of election experts and legal scholars, we have developed legislation that establishes clear guidelines for our system of certifying and counting electoral votes for president and vice president.”

Key Revelations From the Jan. 6 Hearings

Card 1 of 8

Making a case against Trump. The House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack is laying out evidence that could allow prosecutors to indict former President Donald J. Trump, though the path to a criminal trial is uncertain. Here are the main themes that have emerged so far:

An unsettling narrative. During the first hearing, the committee described in vivid detail what it characterized as an attempted coup orchestrated by the former president that culminated in the assault on the Capitol. At the heart of the gripping story were three main players: Mr. Trump, the Proud Boys and a Capitol Police officer.

Creating election lies. In its second hearing, the panel showed how Mr. Trump ignored aides and advisers as he declared victory prematurely and relentlessly pressed claims of fraud he was told were wrong. “He’s become detached from reality if he really believes this stuff,” William P. Barr, the former attorney general, said of Mr. Trump during a videotaped interview.

Pressuring Pence. Mr. Trump continued pressuring Vice President Mike Pence to go along with a plan to overturn his loss even after he was told it was illegal, according to testimony laid out by the panel during the third hearing. The committee showed how Mr. Trump’s actions led his supporters to storm the Capitol, sending Mr. Pence fleeing for his life.

Fake elector plan. The committee used its fourth hearing to detail how Mr. Trump was personally involved in a scheme to put forward fake electors. The panel also presented fresh details on how the former president leaned on state officials to invalidate his defeat, opening them up to violent threats when they refused.

Strong arming the Justice Dept. During the fifth hearing, the panel explored Mr. Trump’s wide-ranging and relentless scheme to misuse the Justice Department to keep himself in power. The panel also presented evidence that at least half a dozen Republican members of Congress sought pre-emptive pardons.

The surprise hearing. Cassidy Hutchinson, a former White House aide, delivered explosive testimony during the panel’s sixth session, saying that the president knew the crowd on Jan. 6 was armed, but wanted to loosen security. She also painted Mark Meadows, the White House chief of staff, as disengaged and unwilling to act as rioters approached the Capitol.

Planning a march. Mr. Trump planned to lead a march to the Capitol on Jan. 6 but wanted it to look spontaneous, the committee revealed during its seventh hearing. Representative Liz Cheney also said that Mr. Trump had reached out to a witness in the panel’s investigation, and that the committee had informed the Justice Department of the approach.

Though the authors do not have the minimum 10 Republican senators needed to guarantee the legislation could make it past a filibuster and to final passage, they hope to round up sufficient backing for a vote later this year.

The legislative effort began after the Jan. 6 attack, which unfolded as Congress met for the traditionally routine counting of the electoral ballots that is the last official confirmation of presidential election results before the inauguration.

In the run-up to the riot, Mr. Trump tried unsuccessfully to persuade Vice President Mike Pence — who presided over the session in his capacity as president of the Senate — to unilaterally block the tally, citing false claims of election fraud.

The new legislation focuses mainly on the handling of electoral votes and does not incorporate wider voting protections sought by Democrats after some states instituted new laws seen as making it more difficult for people to vote following Democratic victories in 2020. Senate Republicans have previously blocked those voting measures.

There is widespread sentiment in Congress that some steps need to be taken to bolster the Electoral Count Act, though there may be disagreement on the specific provisions.

“The Electoral Count Act does need to be fixed,” Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the minority leader, told reporters on Tuesday, saying he was “sympathetic” to the aims of those working on the legislation.

Under the proposal to overhaul the vote count, a state’s governor would be identified as the sole official responsible for submitting the state’s slate of electors following the presidential vote, barring other officials from doing so.

In an effort to prevent frivolous efforts to object to a state’s electoral count, a minimum of one-fifth of the House and Senate would be needed to lodge an objection — a substantial increase from the current threshold of one House member and one senator. Objections would still have to be sustained by a majority of the House and Senate.

Following a standoff over the presidential transition in 2020, when Trump administration officials initially refused to provide President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. the funding and office space to begin preparations for assuming power, the legislation would allow more than one candidate to receive transition resources if the outcome remained in dispute.

After the push by Mr. Trump and his allies to get Mr. Pence to manipulate the electoral count in Mr. Trump’s favor, the legislation would stipulate that the vice president’s role is mainly ceremonial and that “he or she does not have any power to solely determine, accept, reject or otherwise adjudicate disputes over electors.”

Besides Ms. Collins, the other Republican members of the bipartisan group backing the overhaul are Senators Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia, Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Rob Portman of Ohio, Mitt Romney of Utah, Ben Sasse of Nebraska, Thom Tillis of North Carolina and Todd Young of Indiana.

In addition to Mr. Manchin, the Democrats are Senators Benjamin L. Cardin of Maryland, Chris Coons of Delaware, Christopher S. Murphy of Connecticut, Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire, Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Mark Warner of Virginia.

Source: nytimes.com