The parallels between a drawn-out clash for speaker in 1923 and one in 2023 suggest that not much has changed in Congress over a century.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this articleGive this articleGive this article

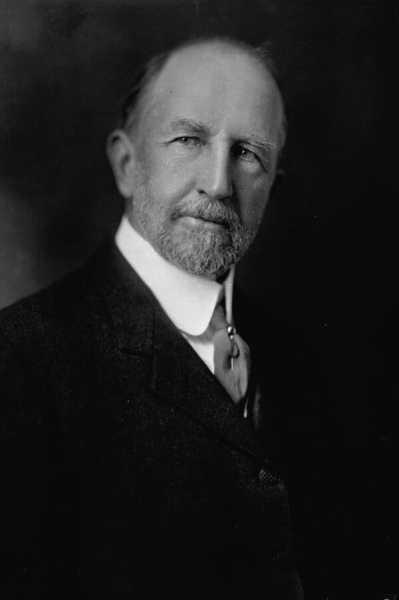

The last time the House required multiple days and repeated votes to settle on a new speaker, Frederick H. Gillett was chosen.

WASHINGTON — The House was in an uproar, unable to settle on its new speaker, forcing roll call vote after roll call vote. The Senate had quietly slipped out of the city while insurgents in the House demanded more power as the nation watched anxiously.

“Radicals Force Deadlock in House as Congress Opens,” blared one national headline.

The year was 1923, almost exactly a century ago, the last time the House required multiple days and repeated votes to settle on a new speaker before this week’s continuing stalemate over the candidacy of Representative Kevin McCarthy, Republican of California.

While it was long before the dawn of Twitter, super PACs and C-SPAN, things really haven’t changed all that much in Congress. In fact, the parallels between then and now are striking, down to the opponents of 1923’s eventual winner, Frederick H. Gillett, Republican of Massachusetts, angling for basic changes in the rules of the House to give them more influence and more top committee slots, just as hard-right adversaries of Mr. McCarthy are doing today.

Unable to overcome the opposition from a band of progressive Republicans, supporters of Mr. Gillett kept pushing the House into adjournment to allow back-room talks about how to resolve the stalemate, another tactic being employed this time around as the vote tallies remain inconclusive.

And the Senate, traditionally viewing itself as the more refined chamber, chose not to hang around for the slugfest in the House. Instead, senators organized without incident and expeditiously vacated the Capitol to let their counterparts across the Rotunda sully themselves alone.

F.A.Q.: The Speakership Deadlock in the House

Card 1 of 7

A historic impasse. Representative Kevin McCarthy of California is fighting to become House speaker, but a group of hard-right Republicans is blocking his bid and paralyzing the start of the new Congress. Here’s what to know:

Why is there a standoff? With Republicans holding a narrow margin in the House — 222 seats to Democrats’ 212 — Mr. McCarthy needs support from his party’s right wing to become speaker. But some far-right lawmakers have refused to back him, preventing Mr. McCarthy from getting to 218 votes.

Who are the detractors? The 20 House Republicans who are voting against Mr. McCarthy include some of the chamber’s most hard-right lawmakers. Most denied the results of the 2020 presidential election, and almost all are members of the ultraconservative Freedom Caucus.

What do they want? The right-wing rebellion against Mr. McCarthy is rooted not just in personal animosity, but also an ideological drive. The holdouts want to drastically limit the size, scope and reach of the federal government, and overhaul the way Congress works to make it easier to do so.

What can McCarthy do? Mr. McCarthy has made several concessions to try to win over the hard-liners, embracing measures that would weaken the speakership and that he had previously refused to support. But so far the concessions have not been enough to corral the votes he needs.

Is there an alternative to McCarthy? A big factor in Mr. McCarthy’s favor is that no viable candidate has emerged to challenge him, but Republicans could coalesce around someone else. Steve Scalise, the No. 2 Republican in the House, is seen by many as the most obvious backup.

How does this end? House precedent dictates that members continue to take successive votes until someone secures the majority to prevail. Until a speaker is chosen, the House is essentially a useless entity. It cannot pass laws or even swear in its members.

“What the Senate really did,” The New York Times of Dec. 4, 1923, reported knowingly, “was to show respect for public opinion and its own dignity by not resorting to wrangling about the election of the president of the Senate. But in the House of Representatives the progressive bloc preferred to advertise itself and its insatiable passion for more places on the committees.”

The 118th version of the Senate did the same this week, convening for a celebratory induction of new members and the swearing in of re-elected senators on Tuesday, then quickly fleeing the capital for three weeks to allow the House to occupy the political stage alone.

While never common, stalemates over the speakership requiring repeated votes to resolve did occur with some frequency in the early days of Congress, almost all before the Civil War when party labels were not so firmly affixed. According to the archives of the House, there have been at least 14 cases of a speaker being chosen through multiple ballots, with the record being 133 in 1856.

But before this year there have been none since Mr. Gillett’s contest, primarily because the two-party system has become so deeply entrenched. Members of the party that won control of the House would typically consider it foolhardy to risk their power and image by engaging in such a risky internal power struggle. Speakers Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat, and John A. Boehner, a Republican, had their challenges in recent elections, but never had to go beyond a single ballot to secure the post.

Plus, Democrats held rock-solid control of the House for four decades before 1994 with their large majorities, allowing the certainty of who was speaker to be settled long before the pro forma vote on the House floor. And while the speaker is theoretically the constitutional officer for the whole House, the position has in reality evolved into the political and legislative leader of the majority party, making it the majority’s privilege to bestow.

To many, the mess on the House floor the past few days has been the best illustration yet of Republican dysfunction, a potential inability to govern and an unfortunate political tendency for the party to devour its leaders. But as they held out against Mr. McCarthy, his Republican opponents sought to portray the return to the days of speaker uncertainty as healthy and a move away from ingrained party power.

“We are making history in this process and we are showing the American people that this process works,” said Representative Scott Perry, Republican of Pennsylvania and a leading McCarthy opponent. “Is it going to be painful? Is it going to be difficult? Yes, it probably is. That’s why it took 100 years.”

John James, a newly elected Republican from Michigan, pointed out on Thursday that the differences that forced the House into a two-month, 133-vote marathon before the election of Nathaniel Banks of Massachusetts as speaker in 1856 were much more consequential than those holding up the speakership of Mr. McCarthy.

“Without question, the issues that divide us today are much less severe than they were in 1856,” Mr. James, who is Black, said in nominating Mr. McCarthy for a seventh round of indeterminate voting. “The issues today are over a few rules and personalities, while the issues at that time were about slavery and whether the value of a man who looks like me was 60 percent or 100 percent of a human being. It was a long, drawn-out, painful process, but it had to happen.”

“On that day long ago the good guys won,” he said. “The leading Republican nominee won then, and the leading Republican nominee will win again.”

In the 1923 fight, the voting stretched over three days — the current deadlock hit three days on Thursday — and Mr. Gillett finally prevailed over Finis J. Garrett of Tennessee by a vote of 215 to 197 on the ninth ballot. That was a quicker conclusion than this year’s version, which saw its 11th ballot end on Thursday without a winner.

Ultimately, concessions made by Mr. Gillett and his supporters swung the bloc of progressive Republicans who had been supporting alternative candidates behind him while Democrats remained united behind their candidate — another familiar scenario.

“The organization of the House proceeded after the speakership election,” The Times of Dec. 6, 1923, reported with an almost palpable sigh of relief.

There was a note of optimism added that might cheer whoever comes out of the current leadership strife.

“Even with his diminished powers,” the newspaper noted, “the speaker is in a position to exercise great influence upon legislation.”

But the whole ordeal may have been too much for Speaker Gillett. The next year he ran for the Senate — and won.

Source: nytimes.com