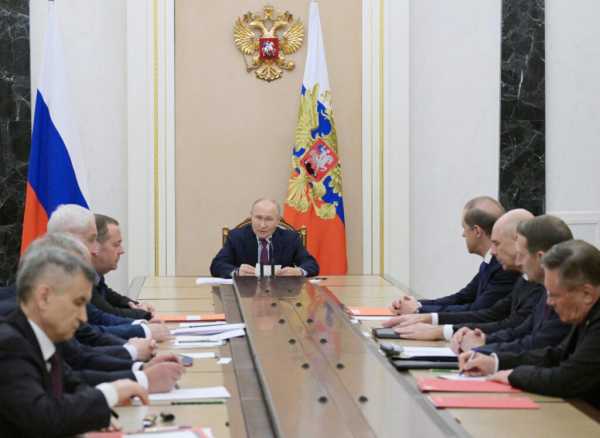

Vladimir Putin has this week proposed changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine that would significantly lower the threshold for the country’s use of nuclear weapons. Addressing a September 25 meeting of senior Kremlin officials, he presented a series of draft amendments aimed at expanding the scope for possible nuclear strikes. Putin emphasized that if these revisions are duly adopted, a conventional attack on Russia by any non-nuclear nation that is backed by a nuclear power would be perceived as a joint attack.

Putin’s televised comments were clearly timed to serve as a direct warning to Western leaders as they continue to debate lifting restrictions on long-range Ukrainian strikes inside Russia. Earlier this month, the Kremlin dictator declared that any attacks on Russian territory using Western-supplied missiles would mean that NATO is “at war” with Russia.

This week’s announcement of revisions to Russia’s nuclear doctrine is the latest in a long line of thinly-veiled nuclear threats made by Putin since he launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. As Russian tanks first rolled across the border in February 2022, Putin indicated that any attempts at Western interference would be met with a nuclear response. Three days later, he hammered home the point by placing Russia’s nuclear forces on high alert.

These early examples of nuclear saber-rattling have set the tone for the invasion, with Putin and other senior Russian officials regularly resorting to nuclear blackmail in an obvious bid to undermine Western support for Ukraine. During one particularly notorious incident in September 2022 as he prepared to “annex” four partially occupied regions of Ukraine, Putin directly referenced his country’s vast nuclear arsenal and vowed to use “all means at our disposal” to defend Russia’s conquests. “This is not a bluff,” he declared.

So far, Russia’s nuclear intimidation tactics have had little discernible impact on decision-making processes in Kyiv. On the contrary, Ukraine’s leaders have repeatedly demonstrated their willingness to call Putin’s bluff.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, the Ukrainian military has liberated entire regions claimed by the Kremlin, sunk or damaged around one-third of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, and conducted a comprehensive bombing campaign of Russian military and energy infrastructure, all without provoking a nuclear response. In August 2024, Ukraine crossed the reddest of all Russian red lines by invading Russia itself. Rather than reaching for his nuclear briefcase, Putin chose to downplay the invasion.

Ukraine’s boldness is striking but not entirely surprising. After all, Russia has made no secret of its intention to extinguish Ukrainian statehood and erase Ukrainian identity. Faced with the existential challenge of Russia’s genocidal invasion, most Ukrainians see no real alternative to military victory and are committed to confronting the Kremlin.

The same cannot be said for all of Ukraine’s partners, however. While countries located closer to Russia such as the Nordic and Baltic nations, the Poles, and the Czechs, have been notably inclined to dismiss talk of red lines, many leading Western countries have allowed themselves to be intimidated by Putin’s relentless nuclear threats. This fear of escalation has enabled the Kremlin to reduce arms deliveries to Kyiv, and has led to the imposition of absurd restrictions on Ukraine’s ability to defend itself. As a result, the Ukrainians find themselves fighting for national survival against a military superpower with one hand tied behind their backs.

It is easy enough to understand why so many in the West seem preoccupied by the idea of avoiding a potential nuclear war. Nevertheless, this readiness to fold when confronted by Russia’s nuclear ultimatums is shortsighted in the extreme and risks plunging the whole world into a dark new era of nuclear brinkmanship.

If Putin’s nuclear blackmail succeeds and enables him to achieve his imperial ambitions in Ukraine, this would set a disastrous precedent with the potential to completely transform the role of nuclear weapons in the international arena. A triumphant Putin would be sorely tempted to use the same tactics elsewhere, while other authoritarian regimes would draw the obvious conclusions for their own expansionist agendas.

Meanwhile, front line democracies from Finland and Poland in the west to South Korea and Japan in the east would be forced to urgently rethink their own non-nuclear status. Stunned by the West’s collective failure to stand up to Russia’s nuclear bullying in Ukraine, many governments would likely decide that the only way to safeguard their national security was by acquiring a nuclear arsenal of their own. The ensuing arms race would undo decades of nuclear nonproliferation progress and dramatically increase the chances of nuclear war.

The only way to avoid this nightmare scenario is by stopping Russia in Ukraine. But for that to happen, the West must first abandon its present zero tolerance approach to nuclear risk and adopt a much more resolute posture toward Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling. Among other things, this would require far firmer public and private messaging that spells out the catastrophic consequences for Russia if Moscow dares to follow through on its nuclear threats.

More than two and half years since the start of Russia’s invasion, it should now be abundantly clear that Vladimir Putin will continue escalating his nuclear blackmail until it stops working. So far, Putin’s ability to intimidate the West has been his greatest success of the entire war, allowing Russia to retain the initiative and set the boundaries of Western support for Ukraine. Unless this changes, nuclear bullying will be legitimized on the international stage and the world will become a far more dangerous place.

Peter Dickinson is editor of the Atlantic Council’s UkraineAlert service.

Source: euractiv.com