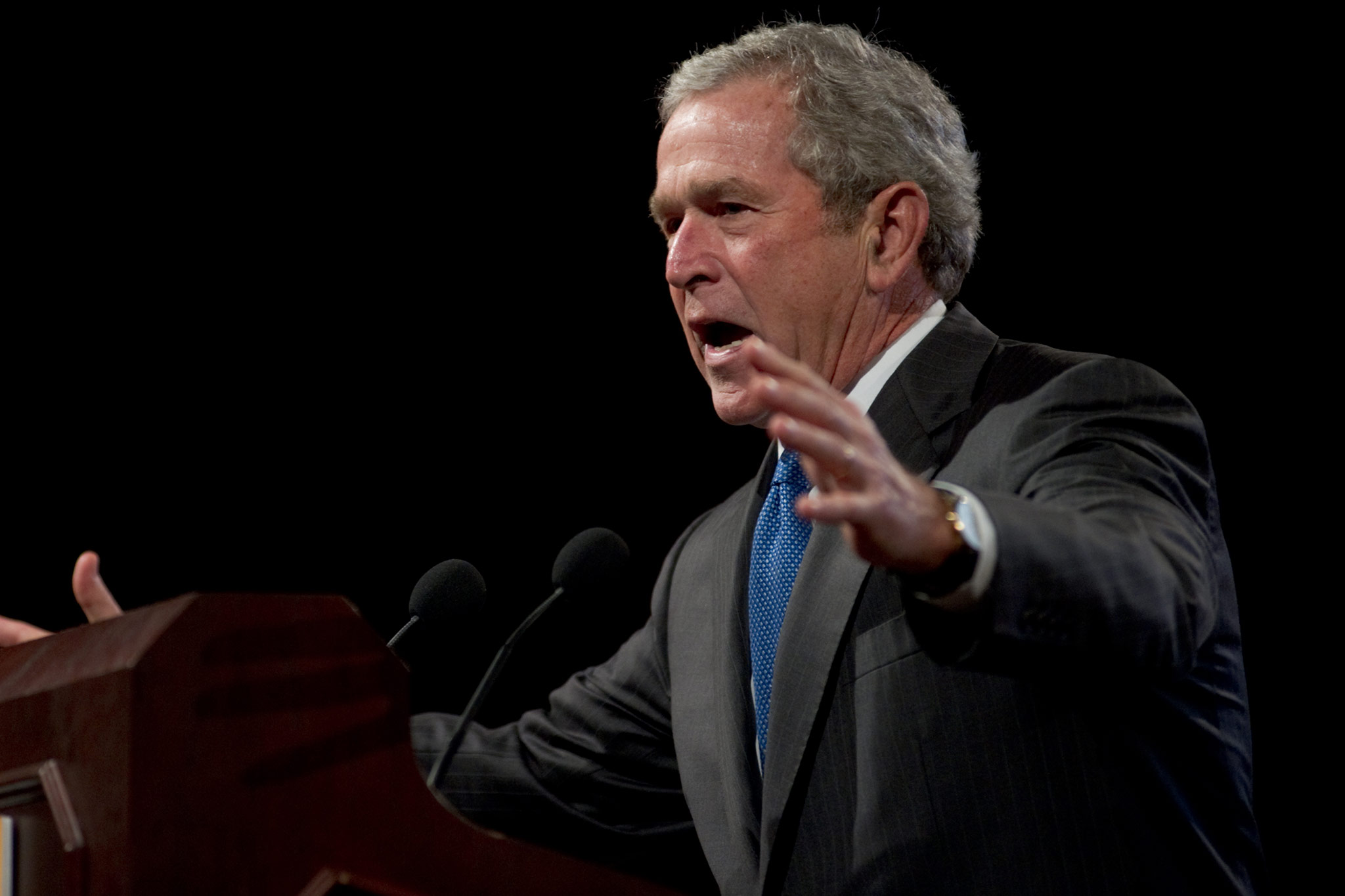

wenty years have passed since the 9/11 attacks in the United States. It was in the immediate aftermath that US President George W. Bush declared his infamous “war on terror” and launched a cataclysmic campaign of occupation in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

In 2001, a US-led coalition invaded Afghanistan to dismantle al-Qaeda and search for its leader, Osama bin Laden, who were harbored by the Taliban government. The presence of foreign troops sent al-Qaeda militants into hiding and the Taliban were overthrown.

In declaring his war, Bush gave the international community an unequivocal ultimatum: to either be “with us or against us in the fight against terror.” In 2003, he took this a step further. He leveraged his power and convinced US allies that Iraq was a state sponsor of terror and its president, Saddam Hussein, had developed weapons of mass destruction, which posed an imminent threat. It wasn’t long before the world found out that this narrative was constructed by the White House as the Bush administration was determined to attack Iraq. The results were devastating: hundreds of thousands of Iraqi deaths, the displacement of over 9 million civilians and the political mayhem that continues to this day.

It has been argued that Islam has been conflated with terrorism not only in the media, but also in much of the political discourse. As a direct result of the war on terror, studies show that an attack by a Muslim perpetrator receives 375% more attention than if the culprit was a non-Muslim.

As these patterns grew with time, countries started to employ their deterrence capacity under the guise of the “war on terror,” only to undermine those who were resisting regimes or seeking self-determination. This was seen in countries like Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Even Russian leader Vladimir Putin, in 2001, quickly persuaded Western leaders that his country faced similar threats from Islamists and was dealt a carte blanche to crack down with brute force on insurgents and civilians alike.

The foreign occupation of Afghanistan ended in August 2021. After 20 grueling and miserable years, the US pulled out from Afghanistan amidst a Taliban takeover, setting a range of events into motion. Chaos filled Kabul Airport as scores of people were desperate to leave the country. The IMF suspended Afghanistan’s access to hundreds of millions in emergency funds due to a “lack of clarity within the international community” over recognizing a Taliban government.

The war led to irreparable damages and hundreds of thousands of Afghans paid with their lives. The US spent over $2.2 trillion on the conflict and had thousands of its soldiers returned in body bags. Today, starving families in Afghanistan are selling their babies for money to feed their children and the world only looks on.

To understand how we got here, I spoke to Anas Altikriti, a political analyst, hostage negotiator and the CEO of The Cordoba Foundation, an organization aimed at bridging the gap of understanding between the Muslim world and the West. In this interview, we discuss America’s handling of the occupation and examine Afghanistan’s next steps now that the Taliban has assumed authority in the country.

The transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kholoud Khalifa: Joe Biden has received a certain amount of backlash from both sides of the aisle for withdrawing abruptly from Afghanistan. What do you make of his decision?

Anas Altikriti: Looking from an American perspective, I believe Biden had no choice. We tend to forget that the president who actually signed the agreement to leave Afghanistan was Donald Trump and his deadline was May of this year. Technically, you can state that Biden was carrying out a decision made by his predecessor. However, in reality — and I think that this is what’s important — any American president would have found it extremely difficult and utterly senseless to carry on a failed venture. Afghanistan and Iraq were utterly horrendous mistakes. If not at the point of conception and theory, the implementation was horrid.

However, from a purely analytical political point of view, Biden had absolutely no choice. The fact that he was going to come in for so much criticism, and particularly from the American right, is no surprise whatsoever. I would like to assume that Biden’s administration had the capacity to foresee that and to prepare for that, not only in terms of media, but also in terms of trying to argue the political perspective. Although in America today, I don’t think that is really useful.

So, generally speaking, I’m not surprised by the fact that he got attacked, because ultimately speaking, on paper, this was a defeat to the Americans. It was a defeat to the Americans on the 20th anniversary of 9/11, the day in which the idea started to crystallize in terms of those who wanted to see American basis spread far and wide, and the whole intermittent 20 years has been nothing but an utter and an abject failure. Thousands of American troops have been killed, but on the other side, probably more than a million of Afghan lives have been absolutely decimated — either killed or having to flee their homes and live as refugees elsewhere. The cost has been absolutely incredible, and for that, I think the Americans can contend with themselves, as history will judge this to be a failed attempt from start to finish.

Khalifa: What are your thoughts on the Taliban as a political actor in today’s geopolitical landscape?

Altikriti: Well, we’ll wait and see. There is no question that from the military point of view, the Taliban won. They achieved the victory, and they managed to expel the Americans and to defeat them not only on the ground, but also at negotiating. For almost the past 12 years, there had been negotiations between the Taliban and the Americans either directly or indirectly, whilst at the same time, the Taliban had been fighting against the American presence in Afghanistan and never conceding for a moment on their objective that they wanted a full and complete withdrawal from Afghanistan. That, itself, is something to be taught at political science departments across the world, and it has definitely affected my own curriculum that I teach to students.

Negotiations, as well as being backed by real power, are things that have proven to be extremely beneficial and quite successful in this particular time. Now, that might be easy in comparison to catering to a nation of 40 million that have been devastated for almost three generations — from oppressive regimes to conflicts, to wars, to civil war, to occupation, to absolute and utter devastation to the rise of violence, ideological militancy, to all sorts of issues that have ravaged that nation.

Governing Afghanistan is going to be a totally different kettle of fish. It’s not the same as fighting. You can say that actually fighting a war from mountain tops and caves is relatively easy in comparison with the task ahead. Whether they’re going to be successful or not is something that we wait to see, and I hope for the betterment of the Afghan people that they will be.

The reality is the Taliban have won and in today’s world, they have the right the absolute right to govern. Hopefully, within the foreseeable future, the Afghan people will have the choice to either hold them to account and lay the blame for whatever economic failures, for instance, or otherwise.

This struggle between nations and their regimes is a continuous one. Thankfully, where we live, in the West, that struggle is mostly done on a political plane. So, we fight politically and we hold our politicians accountable through the ballot boxes. That is not present in many, many developing countries. Afghanistan is definitely a country that needs to find its own model as to how to govern and how to create that kind of balance between people and regime. I think it is utterly hypocritical from the West to prejudge them and hold them to ransom via mistakes that happened in the past. Every administration commits mistakes of varying sorts. Our own government in the UK is now being investigated by an independent inquiry staff as to how it dealt with COVID and whether some of its decisions led to the death of thousands of people. So, mistakes can happen.

The West needs to contend with why they left Afghanistan after 20 years of absolute misery and suffering no better than when they came to it in 2001. That’s a question that the West, including the UK, need to ask themselves before passing judgment on to the Taliban.

Khalifa: You mentioned something very interesting. You said we’re waiting to see and we cannot judge them right now. Do we see any hints of change? Has today’s Taliban changed from the Taliban of the pre-US occupation? For example, the Taliban issued a public pardon on Afghan military forces that had tried to eradicate them.

Altikriti: Well, the hints are plenty and the hints are positive. The fact that the Taliban, as you put it, issued that decree that there won’t be any military trials or court marshals being held. The fact that from the very first hours, they said that anyone who wants to leave could leave and they won’t stop them, but that they hope everyone will stay to rebuild Afghanistan. I think from a political and PR point of view, that was a very, very shrewd way to lay out the preface of their coming agenda.

The fact that Taliban leaders spoke openly, and I’ll be honest, in quite impressive narratives and discourses to foreign media — to the BBC, to Sky — and, in fact, took the initiative to actually phoning up the BBC and intervening and carrying out long and extensive interviews. This has never happened before. We could never have imagined that they sit with female correspondents and presenters and spoke freely and openly. Also, the fact that they met with the Shia communities in Afghanistan at the time when they were celebrating Muharram and assured them that everything was going to be fine.

I think a big part of whether Afghanistan succeeds or not lies in the hands of the West. For instance, in the first 24 hours of the Americans leaving in such a chaotic manner, which exemplified the chaos of the Taliban as we know it, the IMF said that funds to Afghanistan would be withheld. Therein begins that kind of Western hegemony, Western colonization that I believe is at the very heart of many problems in what we termed the Third World or the developing world.

The fact that sometimes nations aren’t allowed to progress, they aren’t allowed to rise from the ashes, they aren’t allowed to recover, they aren’t allowed to rebuild, not because of any innate deficiency on their part, but because of the international order that we have today in the world. We have so many restraining legal organizations — from the UN downwards, including the IMF and the World Bank — that hold nations to ransom. Either you behave in a particular way or we’re going to withhold what is essentially yours. It’s an absolute travesty, but unfortunately, this goes across all our radars. There is very little response in terms of saying, hang on, that is neither just nor fair nor democratic.

If you really, really want the betterment of Afghanistan and Afghan people, countries should be piling in, in order to afford help, to afford aid and to make absolutely sure that the Afghan people have everything they need in order to rebuild for the future.

But, unfortunately, the opposite is happening. We’re tying the nation’s hands behind its back and saying, we’re just going to watch and see how you do in that boxing ring, and if you don’t fare well, that will be justification for us to maybe reintervene in one way or another sometime down the line.

Khalifa: After seizing the country, the Taliban promised an inclusive government, with the exception of women. Yet the current government only comprises Taliban members. What are the chances that they deliver on forming an inclusive government?

Altikriti: I’m sort of straddling the line between being an academic and an activist, and I have a foot in both, so it’s sometimes a little bit difficult. However, I would suggest that when the Conservative Party in Britain wins an election, it’s never assumed that they include people from the Labour Party or Liberal Democrats in their next government. The same goes in America: When the Republicans win an election, you can’t reasonably ask or expect of them to include those with incredible minds and capacities from the Democratic Party — you simply don’t.

So, the hope for inclusivity in Afghanistan needs to take that into consideration. The Taliban are the winning party — whether by force or by political negotiations — and therefore, they have the right to absolutely build the kind of government they see fit. For them to then reach out to others would be an incredible gesture.

But I think it’s problematic and hypocritical if the West doesn’t allow the winning party to govern. If after some time it doesn’t manage to, then maybe you’d expect it to reach out to others from outside its own party or from outside its own borders and invite them to come and help out. But that’s not what you expect from day one.

The fact that they haven’t done what many people expected, and I personally have to say I feared would happen, and it hasn’t. So, until we find that media stations closed down, radio stations barricaded and people rounded up — and I hope none of that will happen, but if it does, we hold them to account.

Khalifa: Imran Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan, says the international community must engage with the Taliban, avoid isolating Afghanistan and refrain from imposing sanctions. He says the “Taliban are the best bet to get rid of ISIS.” What’s your view on that?

Altikriti: If we’re looking back at their track record, they were the ones who managed to put an end to the civil war that broke out after the liberation from the Soviet Union. I mean, for about five to six years, Afghanistan was ravaged with a civil war, warlords were running the place amok. I remember an American journalist said the only safe haven in Afghanistan was something like a 20-square-meter room in a hotel in the center of Kabul. The Taliban came in and created a sense of normality, once again in terms of putting an end to the civil war. There remained only one or two factions that were still in resistance, but otherwise, the Taliban managed to actually bring Afghanistan to order.

It was only after 9/11 and the US intervention that returned the country back into a state of chaos. So, if we’re going to take their track record into consideration, then it’s only fair to say that they do have the experience, the expertise and the track record that shows that they can bring some semblance of normality and peace.

Now, obviously, we understand that Afghanistan is not disconnected from its regional map and from the regional politics that are at play, including the Pakistani-Indian conflict. It’s no secret that the Taliban were looked after and maintained by the Pakistani intelligence. I understand from the negotiations that were taking place since 2010 that there was almost always a member of the Pakistani intelligence present at the table. So, it’s not a secret that Pakistan saw that in order to quell the so-called factions that represented the mujahideen, the Taliban were its safest bet.

In that sense and from that standpoint, you would suggest that the Taliban are best equipped. Much of what was going on in Afghanistan was based on cultures, traditions and norms that Americans were never ready to embrace, understand or accept. That’s why they fell foul so many times of incidents, which could have been easily appeased with only a little bit of an understanding and of an appreciation of fine cultural or traditional intricacies and nuances. The Taliban wouldn’t have that issue.

So, you would suggest that what Imran Khan said has some ground to stand on. It’s a viable theory. But everything that we’re talking about will be judged by what see is going to happen. But before we do that, we need to allow the Taliban the time, so that when we come to say, listen, they fail, we have grounds and evidence to issue such a judgment.

Khalifa: I want to shift to the US. So we know that there was a US-led coalition, and its presence for over 20 years in Afghanistan and in the Middle East led to very little change in the region. You already alluded to that at the very beginning. The US spent trillions of dollars and incurred the highest death toll out of the coalition members. What has the US learned from this experience?

Altikriti: I think that’s the question we should be focused on. I fear that it has learned virtually nothing and that’s very worrying. Just like we were passing pre-judgments on the Taliban, we need to do the same everywhere. If that’s the kind of ruler that we’re using to judge a straight line, it’s the same ruler we need to judge every straight line.

We heard the statements that emerged from Washington, and to be perfectly honest, very, very few were of any substance. Ninety-nine percent, and this is my own impression, were about America looking back and how they let down the translators and the workers in the alliance government and left them at their own fate. The tears were shed, both in the British Parliament as well as the American Congress, which actually shows that these people didn’t get it. They didn’t get it and that is what worries me the most.

If something as huge as Afghanistan and what happened — this wasn’t a car crash that happened in a split second. This was something that was led over the course of the last 17 years and definitely since President Trump signed the agreement with the Taliban in 2020. This should have been a time for politicians and analysts to actually read the situation and read the map properly. But it seems that they never did and they never bothered to see if there was any need or inclination to take lessons from it.

I’m yet to come across a decision-maker, a lawmaker, a politician, a senior adviser to come out and say there were horrendous mistakes carried out by the occupation and by the other alliance governments that led to this, and as a result, we need to learn what to do and not do in future. But there is this arrogance and pride that forbids us from doing so, and as such, they’re inclined to make the same mistake time and time and time again.

Khalifa: Given that the so-called war on terror, and more specifically the occupation in Iraq, was an utter failure, what is the probability in your opinion that America will engage in another foreign intervention?

Altikriti: From a purely political view, I find this extremely far-fetched in the foreseeable future. The reasons being that Americans had to endure bruising at every single level and because of the crippling economic crisis. So, it’s extremely difficult to launch an intervention or military intervention in the way that we saw in Iraq, Afghanistan or Panama in the next two to three years. But the thing is, often, American politics is driven by corporate America.

I mean, we talk about the trillions spent, but like someone said in an article I read in The Washington Post, that those trillions were more than made up by American corporations, by American oil, by getting their hands on certain minerals in Afghanistan. Even the drug trade itself, which Britain and America thought they would quell, it was actually the Taliban who brought it under control, who actually went around and burnt the poppy seed farms. The West reinvigorated that tradeline and stabilized it. Therefore, as a friend of a friend tells me, he says many of those who were scrambling for airplanes in Kabul Airport were poppy seed farmers because they knew that they had absolutely no future under the Taliban.

So, once we count the trillions incurred by the taxpayer, we forget that there is another side that you and I probably don’t even know that is gaining riches at the expense of the Afghans.

The beast now is to try out new weapons. Lockheed Martin and others will always have a vested interest in trying out the new technology, and what’s better than to try it out in real-life situations? If I was to speak to any modern, contemporary, 30-something-year-old military analysts, they’d laugh me off because I’m speaking about a bygone age. We’re talking now about wars where we don’t involve human beings. I mean, in terms of the assailants, they’re flying drones, and there’s an intelligence level to it that I can’t fathom nor understand.

Another aspect that no one is talking about almost is the privatization of militaries. We’re coming now to find brigades, thousands of troops that are mercenaries, people who fight for a wage. Now, this is the new way to fight wars: Why would Britain employ some of its brightest and youngest when it could pay £100 a day to have someone else fight wars on its behalf? And this is now becoming a multibillion-dollar industry. It first started out as a reality in Iraq, when we had the likes of Blackwater who were guarding the airports, presidential palaces and government officials. You’d try to speak to them only to realize they were from Georgia or Mozambique or elsewhere, and they don’t fall under the premise of local law. Therefore, if they kill someone by mistake, you can’t take them to court and that’s the contract you sign. That is where I think the danger lies.

Khalifa: In 2010, you appeared on Al Jazeera’s “Inside Iraq” alongside the late Robert Fisk and Jack Burkman, a Republican strategist. Burkman described Arabs and Muslims as a “bunch of barbarians in the desert” and the Bush administration as the savior bringing change. With its failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, has the US perceptions of Arabs and Muslims changed, and if so, how?

Altikriti: I’d love to have a chat with Jack right now to see what he thinks 11 years on. To answer your question, it saddens me to say that yes, it’s changed, but only because America and American society are so polarized and so divided. It only took Donald Trump to become president or 50% of Americans to defy everything that Trump said. Being anti-Trump meant standing up for Muslims when he issued the Muslim ban for flights. So, people from their standpoint of being anti-Trump said, no, Muslims are welcome. It’s absolutely the wrong way to go on about it. That’s not how we recognize, for instance, that racism is wrong or evil.

However, the fact is that in the past, anti-Muslim sentiments were everywhere and the feelings that Jack Burkman expressed so horribly in that interview were widespread. I personally believe they still remain because 9/11 has become an industry and that industry has many facets to it. Part of it is ideological, part is media, part is educational and obviously part transpires into something that is military or security-based.

We still have Guantanamo. Why is it that the American people aren’t talking about Guantanamo to the extent that they should be? This is something that is on the conscience of every single American citizen — it is paid from their own taxes. Why no one talks about it is simply because no one dares touch the holy grail — the industry of 9/11. It’s a huge, huge problem.

I still believe that those sentiments expressed by Jack back then are still prevalent, but like I said, they were mitigated by the advent of Trump and by his declaration against Arabs and Muslims. This, as well as the highlighting of certain issues by the left in America, such as the gross crimes committed by the Saudi regime and that’s helped in two ways. Firstly, you expose the crimes committed by Saudis, but it’s also cemented that view that Arabs are barbarians.

Khalifa: Afghanistan wasn’t the only country that suffered. Iraq suffered more dire and devastating consequences from the so-called war on terror. What does a future look like for Iraq now that the US has withdrawn?

Altikriti: Oh, very grim, very, very grim. The Americans haven’t withdrawn — they’re less visible. There are current negotiations regarding the next Iraqi government in the aftermath of the elections that we’ve just had, which shows that the Americans are heavily involved.

Iraq is the playground of Iran. So, therefore, any policy of America or Britain or Europe that involves Iran has to have Iraq in the middle.

There are still about three or four American military bases, and from time to time, we hear the news that certain militias targeted this base or that base where Americans lie. Now, the personnel who are there within the bases might carry ID cards as construction workers, advisers, legal experts, bankers or whatever. But ultimately, they’re all there to represent the best interests of the United States. So, America is still there.

However, Iraq is in dire straits. I think the indices that go around every year that show us levels of corruption, levels of transparency, levels of democracy, levels of happiness of people and satisfaction — Iraq is regarded as one of the 10 worst countries on every single level. I think that shows what’s been done to Iraq and what’s been done to the Iraqi people.

The fact is that we have at least 30% of the Iraqi people living as refugees, either within Iraq or outside of Iraq. The fact that in an election only 20% of the people choose to take part.

You have to ask serious questions. You have to say, OK, so when the Americans accused Iran — and I’m a believer that Iran is the worst of all players in Iraq. But you have to ask: So you occupied the country, why did you allow it to happen? So, you can’t just brush it off and say, well, the Iranian militias and its people and its proxy agents in the sun. Well, what were you doing there? So, I think that, again, what has been done to Iraq and to all Iraqis — regardless of their faith, regardless of their sect, regardless of their ethnicity — all of what has happened is a stain. A huge, huge one on the consciousness of everyone in Britain, America, Spain and all the countries that signed up for this and took part in this, everyone has a responsibility to answer.

I mean, obviously, when we spoke about Afghanistan, we didn’t speak about the crimes, the actual crimes that were committed. The one that we come to recognize and know about is the crimes committed by the Australians, where they actually trained the young cadets to shoot at people and kill them to be acknowledged as soldiers. We didn’t talk about that because there are so many of those that were committed. To speak not of Arab and Muslim barbarity, but of Western barbarity — that’s something I think should be discussed.

Khalifa: In Egypt, it was a military coup in 2013 that overthrew a democratically elected government led by the Muslim Brotherhood. In Tunisia, a constitutional change led to the fall of Ennahda, an Islamist party. In Morocco, it was the people who voted out the Justice and Development Party, which ruled the country for 10 years and suffered a massive defeat in September; they went from having 125 seats to only 12. To juxtapose this, in Afghanistan, the Taliban conquered the country overnight from the US, the most powerful country in the world. What message does this send to Islamist parties in the Muslim world?

Altikriti: Only yesterday, I was discussing this with a group of colleagues, and someone repeated a statement that was sent to me by a fellow of Chatham House. He said to me something quite interesting. He said: “Don’t you see that many around the world, particularly young Muslims, will be looking to Afghanistan — and three months ago in Palestine and what happened there — and think to themselves that the way forward is to carry guns.” I said: “Listen, my friend, you’re saying it. I’m not.”

But in reality, it’s unfortunate that many of my own students are saying, “It’s been proven.” I mean, they say, “you academics, you always talk about empirical evidence. Well, here it is: Politics doesn’t work. Democracy doesn’t work. The ballot box does not work. What does work? There you go, you have Taliban, you have the militias. So go figure.” Unfortunately, that is the kind of discussion that I think will dominate the Muslim scene, particularly the political Muslim scene.

For the next few years, I believe, whilst we analyze political Islam and Islamic parties, whether in Egypt, Morocco or Tunisia, that will be the question. Is it a viable argument to say that these parties will have absolutely no chance, either immediately in the short run or in the long run? In Tunisia, they were allowed to run for about 10 years. In Morocco, they were in government for about 10 years. Before that, they were in opposition and they were thriving. But in Egypt, they weren’t allowed to stay for more than a year. So, ultimately, the end is inevitable. So, is it the need to shift and change tactics? It’s going to be quite an interesting and, at times, problematic discussion, but it’s a discussion you need to have.

And last, by the way, on this particular point, the West did not allow democracy, particularly in Egypt and in Tunisia, to exist. We spoke of democracy, we spoke of human rights, we spoke of freedoms, but when they all came to be crushed, the West did absolutely nothing, which told the others well, you know what? They don’t care, there are no consequences, and that is why it is that many, many Muslim youth today will say, well, there’s only one way to go there.

Khalifa: And lastly, what do you believe are the core causes for Islamic extremist groups, i.e., Daesh or al-Qaeda, to still have a foothold in the region, and in your opinion, what is the best way to combat these groups?

Altikriti: Their biggest arguments, and which works well for them, is the fact that democracy failed and that they got nothing from buying into Western values of how to run their societies.

Their biggest argument now will be the Taliban and how they won. So, those are the main standpoints [for] these extremist groups; they lie on people’s frustrations and their feelings that there is no other way out. That’s essentially the argument. I’ve seen it in groups where someone is trying to recruit for that idea. Their bottom line is it doesn’t work. There is no other way — that’s their only argument.

It’s not theological, by the way. People think they are basing it on these Quranic verses or on hadiths [sayings of Prophet Muhammad], but they absolutely do not, because on that particular front, they lose, they have no ground to stand on. [For them,] it’s the fact that, in reality, it doesn’t work — democracy doesn’t work. Human rights doesn’t work. Because ultimately, your human rights mean nothing to those in power. So, killing us is as easy as killing a chicken. It’s nothing. That is their argument.

So, it’s going to be a struggle, it’s going to be a big, big, big struggle for people who want to advocate democracy, want to advocate civil society and diversity. It’s a struggle we can’t afford not to have, we can’t afford not to be in there, because the outcome, the costs will be so hefty on every single part and no one will be excluded.