Dear readers,

Welcome to EU Politics Decoded where Benjamin Fox and Eleonora Vasques bring you a round-up of the latest political news in Europe and beyond every Thursday.

This week we look at Giorgia Meloni’s new right-wing government in Italy and assess the likely gap between her Brussels-bashing rhetoric on the campaign trail and the reality of governing in an economic crisis.

Editors take: Nationalism meets the hard reality of the EU recovery fund

This week saw major speeches by two main leaders of the populist right who both frighten and infuriate Europe’s political establishment; Hungary’s Viktor Orban and Italy’s new Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni. Both offered plenty of red meat to their supporters.

“Let us not worry about those who are shooting at Hungary hidden in the shadows, somewhere from the watchtowers of Brussels,” Orban told Fidesz supporters at a rally to mark the anniversary of the Hungarian Uprising in 1956.

For her part, Meloni, who has shared campaign platforms with Orban, defended him in the Italian parliament on Tuesday, claiming instead that by not working on a lower EU gas price, it was Germany which was ‘anti-European.’

But while that rhetoric might work at home, it is now coming up against the hard economic reality that neither government can do without the financial largesse offered by Brussels.

Having voted against the EU recovery fund and demanded the re-write and renegotiation of Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Meloni has changed tack. Instead, she calls for minor changes to be agreed upon with the European Commission to take stock of energy and raw materials price increases.

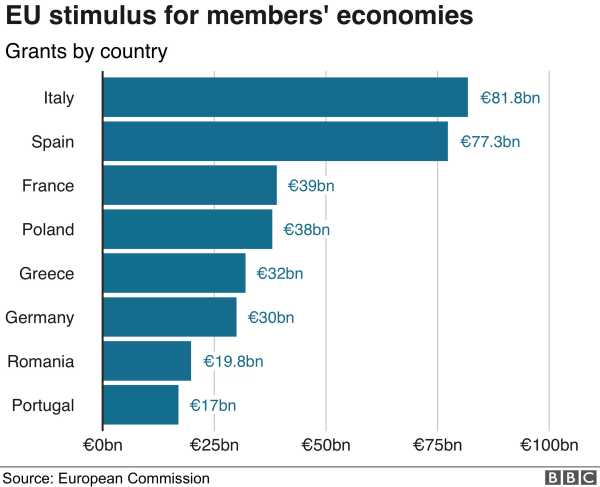

There are 200 billion reasons, the amount that Italy stands to receive in grants and loans, why Meloni has backtracked. Without the recovery fund money, Italy would face massive budget cuts and bond market pressure.

Similarly, Zsolt Nemeth, who chairs the Foreign Affairs Committee in the Hungarian parliament, says that his Fidesz government needs “every penny” of the €27 billion allocated under its recovery plan, which has been stalled because of the long-standing dispute with the EU over the rule of law, and now corruption, concerns.

“It is our money that we are begging for in Brussels,” says Nemeth. That is an arguable point, given that Hungary is a substantial net beneficiary from the EU budget. Besides, purely in realpolitik terms, it does not matter whether it is true or not. The European Commission has control over the disbursement of cash.

After years of bemoaning the propensity for prime ministers to bash Brussels at home but then make nice at EU summits, finally, the EU executive has leverage – in the form of its AAA credit rating that allows it to borrow more cheaply than almost all member states – to compel countries to keep to their treaty commitments.

Italy and Hungary both have BBB credit ratings, while Poland, which has also seen its recovery fund money delayed by disputes over judicial independence, has a marginally better BBB+ rating.

For all their unrelenting criticism of the EU and its institutions and claims of a ‘culture war’ being waged against them, neither Orban nor his ministers have ever entertained the idea of leaving. The obvious conclusion is that they can’t afford to.

_112526484_eu_grants-nc.png

Editor’s take – Meloni’s balancing act

Like every new political phenomenon, Meloni’s government will be in the spotlight for a while, and it is still hard to identify where the experiment is heading.

It is possible to outline some general approaches, like the support for a more intergovernmental EU, her Atlanticism and stances in favour of Ukraine.

However, several ambiguities remain.

The latter lies in the tension and contradictions between her strong ‘populistic nationalism’ and her idea of reliability.

“The politics of announcement, hyper-identitarian and nationalist, of which Giorgia Meloni could make herself the interpreter in the years when her party was a marginal political force, has given way to the politics of reliability,” Marco Damiani, professor of political science at the University of Perugia, told EURACTIV.

“For Fratelli d’Italia, the challenge is to govern while preserving its identity and political position,” he said.

She is now trying to do so, applying two different narratives in Brussels and Rome. A strong nationalism at home and reliable, constructive and cooperative behaviour abroad, in line with the EU establishment.

She is not the first leader to do so, but the differences will be more and more marked in the next months and harder to reconcile. Particularly because of her political alignment with the Hungarian and Polish governments and the possible renegotiation of the recovery plan.

For the first point, we have to wait for the next summit. Mario Tarchi, professor of political science at the University of Florence, told EURACTIV that she may try to mediate between Orban’s positions and those more aligned with the EU leadership.

However, her loyalty to Orban continues.

During her speech in the Italian parliament on Tuesday, she pointed out that sovereigntists do not rule the EU and accused Germany of not having a pro-European approach towards gas, which she conceded, “I might understand.”

As for the recovery plan, she appears to have changed tack from her position during the electoral campaign. From supporting its complete re-writing, she now wants to rewrite the tenders to adapt them to higher raw material prices.

It is not clear what she means in practical terms, but it is unlikely Meloni will have much leverage in renegotiations.

Italy is among the biggest beneficiaries of the recovery plan, funds from which will shape investments for the next decade, with the public expecting the money to flow soon.

It is hard to explain to non-Italians the evolution of right-wing parties with roots in Italian fascism. Firstly, there has been more than one period and type of fascism in the country. Secondly, some fascist features survived and entered Italian society rather than being constrained only to political parties and movements.

Professors Tarchi and Damiani say that Fratelli d’Italia has accepted the democratic game within national institutions, and there is no risk of Italy lurching towards authoritarianism.

According to Tarchi, what remains from the fascist period in Fratelli d’Italia is their nationalism, which is always a key part of Meloni’s narrative.

“Fratelli d’Italia will not demonise fascism, but neither will it be apologetic,” says Tarchi.

Meanwhile, Damiani points to the symbolism in Fratelli d’Italia’s logo, a clear reference to the Italian Social Movement, the party formed in the late 1940s by supporters of Benito Mussolini.

“For Fratelli d’Italia to combine past, present and future in a coherent manner will be an arduous task,” says Damiani.

Across the capitals

Meloni changes tack on Europe

New Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni told the Italian parliament that her government will be a ‘reliable partner’ in the EU; in a speech that sought to assuage concerns from Italy’s EU neighbours that she will run a eurosceptic and far-right government, Meloni told Italian lawmakers that “Italy is fully part of Europe and the Western world,” and would “continue to be a reliable partner of NATO in supporting Ukraine.”

Sunak’s coronation

After the collapse of Liz Truss’s six-week stint in Downing Street, her successor Rishi Sunak became the UK’s fifth prime minister since the Brexit referendum, uncontested after Boris Johnson and Penny Mordaunt both pulled out of the Conservative party leadership contest.

Sunak inherits a bitterly divided party over 20 points behind the Labour party in opinion polls and faces the prospect of imposing major tax rises and spending cuts in the coming weeks.

Macron faces down no-confidence motions

In Paris, Emmanuel Macron’s government used the constitution to head off a parliamentary vote that could have struck down its budget for 2023, prompting two no-confidence motions by the right and left. Though both motions were comfortably defeated, it points to the fragility of the Macron government, which lacks a majority in the National Assembly and highlights the difficulty it faces in passing bills.

No time for a budget

Bulgaria’s caretaker government will not present a draft 2023 budget to parliament, Finance Minister Rositsa Velkova said on Tuesday (25 October), potentially leaving its successor with the tough choice of either breaching EU fiscal rules or slashing spending.

Velkova told lawmakers that the caretaker government would propose extending the 2022 budget into the new year when a permanent government will hopefully be formed.

Who’s electioneering

The centrist Moderate party is the surprise package of the Danish election campaign ahead of polling day on 1 November. The party led by Lars Løkke Rasmussen has jumped from 2% to 11% over the last month, according to opinion polls, leaving it likely to emerge as the third largest party behind the governing Social Democrats, who are polling at around 25%, and the opposition Liberal party on 13%.

The numbers suggest that the left-wing bloc will fall a handful of seats short of the 90 it needs to form an overall majority, potentially leaving the Moderates as a decisive factor in forming a government.

Inside the EU institutions

Health Union EU health ministers have adopted three new regulations that will form the basis for a ‘European health union’ to improve preparedness for cross-border health threats.

We need EU-Africa treaty

The EU needs to finalise and implement the successor to the Cotonou Agreement governing trade and political relations with the African, Caribbean and Pacific community, say MEPs. The agreement, though finalised over a year ago, has not been ratified, partly because of opposition from the Hungarian government to its provisions on migration.

Energy cap split

Energy ministers are still split about price caps on energy bills following the latest meeting in Luxembourg but have moved closer on the question of joint gas purchasing,

Uber under attack

Uber Files whistleblower Mark MacGann attacked the scale of Uber’s influence over EU policy-making at a European Parliament hearing on Tuesday. The company’s former top EU lobbyist, MacGann, called for new EU law to protect platform workers and to return power from the “powerful to the powerless”.

What we’re reading

Lewis Baston reckons Labour is heading for a Tony Blair-style landslide in the next UK election (Financial Times)

Giulia Bottaro says that Meloni will need to maintain close EU ties (Daily Telegraph)

Source: euractiv.com