The French are about to vote on Sunday (19 June) in the second round of legislative elections and could hand the recently re-elected President Emmanuel Macron a victory, but no parliamentary majority and strong opposition from the left.

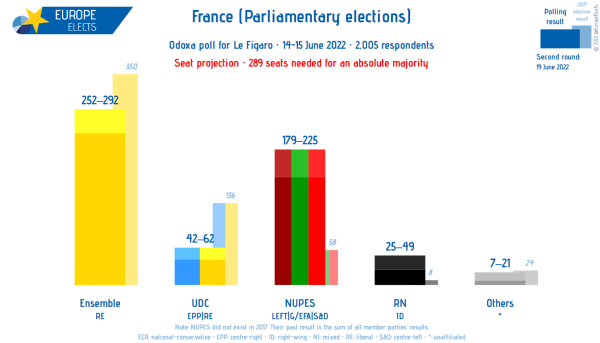

According to the latest projections, the coalition in support of Macron is likely to secure the most seats in the National Assembly, but it may fall short of a majority, forcing the president to govern with other parties or seek a majority on a case-by-case basis.

A strong left

The left alliance, known as NUPES, which has made significant progress in recent weeks, still hopes to reach the threshold of 289 deputies to obtain an absolute majority and thus force Macron to appoint the leader of the radical left Jean-Luc Mélenchon as Prime Minister.

However, most opinion polls suggest that NUPES is unlikely to win more than 220 seats.

FVYzb3XXsAA5VTH [Europe Elects]

That could still deliver five years of volatility with an emboldened left led by Mélenchon’s party on the radical left-wing of the Assembly. The presidency of the Finance Committee is typically held by the opposition and is granted extensive powers, notably in terms of control and hearing the government, promising a rough ride for Macron’s government.

But the future of the left-wing coalition is uncertain: from the outset, the parties that form it have indicated that they will sit in separate groups and have not reached an agreement on certain issues, including foreign affairs, NATO, and secularism.

The Macronist camp could use these levers to divide and weaken the left.

The risk of a ‘cohabitation’ ruled out?

In the event of minority rule for the presidential movement, Macron’s party could find itself struggling to pass laws and initiatives promised by the president during the election campaign.

NUPES should neither propose nor accept a government pact with Macron, Sandrine Rousseau, leader of the radical left-wing of the Greens, told EURACTIV.

Therefore, it is to the right that Emmanuel Macron and Elisabeth Borne could turn for the reforms they are considering. The Les Républicains group – expected to have between 40 and 70 deputies – could become a key ally for the government. However, these would still be historically low numbers for the centre-right party.

If some have pushed for a government pact with Macron, like the former boss of the Republicans, Jean-François Copé, others like Rachida Dati say that the right will evaluate and vote “on a case by case basis” on government proposals.

Proposals such as the extension of the legal retirement age to 65 or investments in nuclear energy could therefore still be adopted despite the absence of an absolute majority.

There is no doubt that, if necessary, negotiations will begin the day after the vote, though their outcome is impossible to predict.

But, much more than in 2017, Macron will also have to deal with his allies: the confederation “Ensemble!” brings together several movements and parties, including Renaissance (ex-La République en Marche), the centrist party MoDem and the centre-right movement Horizons led by former Prime Minister Edouard Philippe.

With a weakening of the Renaissance group – which is expected to lose many MPs – the influence of groups from the other parties in the coalition is likely to be much greater than before and could shift President Macron’s policies towards the right in particular.

A stronger far right on a low turnout

These parliamentary elections could also see the emergence of a far-right parliamentary group for the first time since 1988 if Marine Le Pen’s party exceeds 15 elected MPs, which is widely expected. This would give them additional power in speaking time and influence on the parliamentary agenda.

In the first round of voting last Sunday (12 June), fewer than one in two voters cast a ballot. Among the youngest, 70% did not go to the polls, a pattern set to be repeated on Sunday. Apathy and a divided parliament point to a tough second term for Macron.

[Edited by Benjamin Fox]

Source: euractiv.com