Incumbent French President Emmanuel Macron is within reach of re-election in the second voting round on Sunday, but his far-right rival, Marine Le Pen, cannot be dismissed as the French seem more divided than before.

On Sunday, France will choose between the two starkly different projects offered by Macron, qualified as an elitist liberal, and the populist Eurosceptic Le Pen. The stage is the same as in 2017, but the voters appear more divided now, overshadowed by weariness and disillusionment.

Macron favoured, but Le Pen’s win still possible

Voting intentions indicate an advantage for Macron, albeit with a much smaller gap than in 2017 when he also faced off against Le Pen. Back then, he benefited from novelty and did not attract as much criticism as he does today.

At the time, Le Pen still struggled with a very negative image, perceived as the torchbearer of the French far-right and the heiress to her father, Jean Marie Le Pen.

In the meantime, she has moderated her more radical views and vowed not to take France out of the EU if elected but to change the bloc “from within”.

By focusing her campaign more on the theme of purchasing power, the primary concern of the French, she has gained even more ground among the working classes.

Also, the arrival of anti-immigration extreme-right candidate Éric Zemmour into the political landscape has completed the ‘de-demonisation’ of Le Pen and her party in the eyes of many French people.

Interviewed on France Inter this week, Brice Teinturier, political scientist and deputy director-general of the Ipsos France polling institute, said that “there is an undeniable advantage” for Macron. But he cautioned that “a very large victory for Macron [as in 2017] is very unlikely”.

“Kingmaker” voters

Unlike in the previous election, a victory for Le Pen remains possible, and this prospect sends shivers through the corridors of EU power in Brussels and most of Europe.

The leaders of the Spanish, Portuguese, and German governments took a rare step to pen an open letter on Thursday urging French voters to re-elect Macron, EURACTIV’s partner EFE reported, breaking with the long-standing tradition of not interfering in domestic elections of another country.

Teinturier identified three conditions for Le Pen to have a chance of being elected.

First, the voters who abstained in the first round, nearly 13 million people, chose to cast their ballot in the second round and do so “more for Marine Le Pen than for Emmanuel Macron”.

Second, if Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters ignore his advice “not to vote for the far-right” and split their votes between Macron and Le Pen.

At this stage, about a third of those who voted for Mélenchon say they will vote for Macron, with one in five for Marine Le Pen. For the moment, the remaining half wish to abstain or vote blank.

This is a notable difference from 2017 when half of the radical left-wing voters went for Macron in the second round, and less than one in ten chose Le Pen.

The third condition is a lower mobilisation of Macron’s voters, which would benefit his opponent.

Therefore, Teinturier concluded, “the victory of Marine Le Pen is not to be excluded”.

The tactics of the two camps

Macron and Le Pen adopted two very different strategies in the aftermath of the first round.

Macron chose direct contact with citizens by travelling on the ground – a stark contrast to his low-key campaign in the first round.

Le Pen sought to “presidentialise” her image through long thematic press conferences to seduce voters who still doubted her ability to run the country.

After the second round, a “third round”?

But Sunday’s vote is just the first half of the French electoral reshuffle. All political parties already have their eyes on the June legislative elections, which could complicate the political balance of power in the country and have already been labelled by some pundits as a “third round” of the presidential election.

This is when the table could turn if the French choose a majority in the Assembly hostile to the new head of state. If this were to happen, the elected president’s power would be severely diminished.

What is the state of mind of the French?

What is certain is that this election is creating tensions within society.

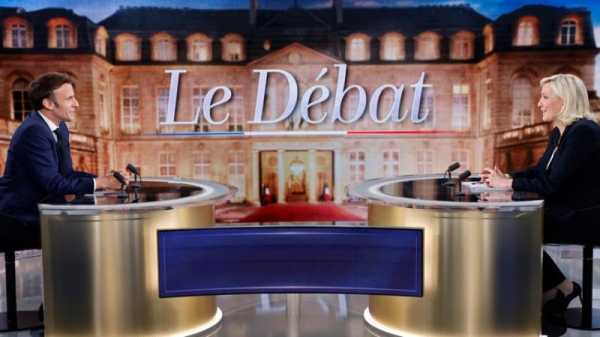

After a televised debate between the two candidates on Wednesday, Adrien, a sixty-year-old who knows the left-wing circles well, summed up his concerns: “I hear around me many people who see Macron and Le Pen back-to-back, who say that it is the same thing to vote for one or the other. This saddens me because it is not true”.

And to those who reproach Macron for being “arrogant” or “right-wing”, he retorted: “Yes, it’s less serious to be arrogant than to be a fascist […], and yes, it’s less serious to be right-wing than extreme right-wing” as Le Pen is, he asserted.

Victor, a Parisian artist and Mélenchon voter who listened to the debate, disagreed. While he would like to “block” Marine Le Pen, “the character and the neoliberal and Eurobait ideology” of Macron makes it difficult for him to give him his vote. The “absence of mea culpa” from Macron is also a determining factor.

Victor, therefore, hesitates between voting for Macron and casting a blank vote but warns that he does not want to “confirm Macron in his authoritarian drifts of the last five years, where he has not stopped flirting with the extreme right”.

Between the liberal and pro-European candidacy of Macron and the populist and Eurosceptic candidacy of Le Pen, some have defined this election as a confrontation between “France from above” and “France from below”.

This distinction partly explains the hesitations of a significant part of an electorate that, without being far-right, is angry with Emmanuel Macron, guilty of having neglected, or even worsened, the issues of social justice and global warming while at the same time being aware of the danger and risks that the arrival of Marine Le Pen at the Elysée could provoke.

(Davide Basso | EURACTIV.fr – Edited by Zoran Radosavljevic, Alice Taylor)

Source: euractiv.com