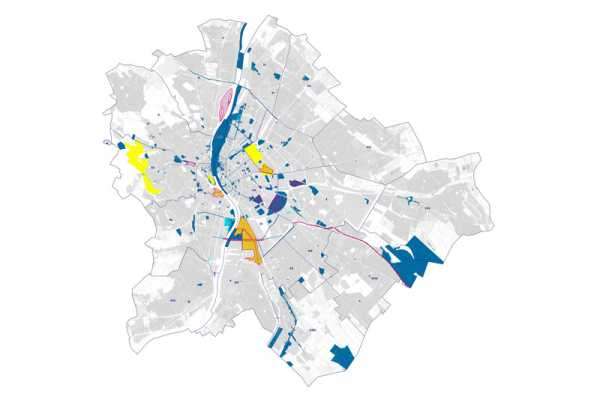

Map of proposed developments in the Hungarian capital, Budapest (see key) (Photo: Budapest Főváros Városépítési Tervező Kft./ City Hall’s urban planning Ltd)

The Hungarian parliament is about to adopt a new law that will transfer the ownership of three central public squares in Budapest from the municipality — to the state.

In return, the state is handing over asset-management rights to the respective city district — which happens to be run by the governing Fidesz party.

-

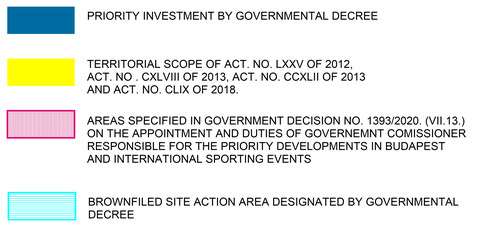

Key to projects on map (Photo: Budapest Főváros Városépítési Tervező Kft. / City Hall’s urban planning Ltd)

(In Budapest’s two-tier municipal system, Viktor Orban’s democratic opposition holds the majority in the City Council, and in 14 of the 23 district councils.)

Trying to explain the reasoning behind the move, pundits have speculated on prospective business property developments, and other possible private gains that the popular Christmas fair and similar public events in these urban spaces can bring to businesses close to the ruling elite.

But this arbitrary takeover is not a stand-alone move.

Green mayor vs hard-right government

Since Gergely Karacsony, the opposition’s green candidate was elected mayor in 2019, Orban’s government has actively worked not only to constrict the city’s budget, and thereby impede its operations, but also to appropriate urban areas and monopolise large-scale development.

It has taken away the local government’s authority for development consent, and has repeatedly side-stepped the democratically elected City Council, public opinion and expert advice.

Using its legislative powers, the government also created a parallel structure of urban mobility planning, and, crucially, exempted a wide range of building projects from regular authorisation and licensing.

These shortcuts serve several purposes.

First, they enable Orban to one-sidedly implement massive investments and define Budapest’s cityscape for decades to come. This way the government can push through its value-laden urban priorities (carbon-heavy prestige investments, national conservative restoration projects, professional sporting facilities) despite a non-supportive city population.

Just as important, the special administrative procedures eliminate obstacles to corruption and allow for the commissioning of government-friendly subcontractors.

Last, the top-down urban planning zeal establishes the political narrative that the central government, not the green mayor, is advancing spectacular development in the capital.

Evidently, not all of the government’s initiatives are equally problematic from the urban improvement perspective, nor are they all objectionable for the City Hall.

Yet, most of these investments are vehemently critiqued by local officials, urban experts and green organisations on grounds of misplaced urban objectives, transparency concerns and a total lack of dialogue at a local level.

‘Consultation’ body barely meets

The government did create a mock negotiation platform, the Council for Public Development in the Capital City (FKT) to coordinate development plans with the City Hall.

This, however, was neither intended nor designed for genuine consultations. Since Karacsony was elected mayor, it has only met five times, not holding a meeting since May 2021.

As for parallel structures, the government established a non-profit state company, the Budapest Development Centre (BFK) as the “professional hub of the government’s development activities in Budapest”.

BFK was a lavishly-funded and well-staffed urban planning centre focusing mainly on large-scale mobility projects.

As such, many of its plans would have normally fallen under the purview of the local government, and ran parallel to the development strategies of the capital city’s own public transport company.

Over the past two years BFK put out a substantive suburban railway strategy without engaging at all with the city, published several grandiose project plans, and took over the long-planned Galvani-bridge project that would connect South Buda and South Pest through the Northern tip of Csepel Island.

After the elections in April 2022, legal amendments were made so that the “state’s responsibilities and obligations with regards to Budapest’s urban development” now apply not only to the non-profit company, but also to the newly established Ministry for Constructions and Investments.

BFK is currently being re-modelled, but the government continues to prioritise autonomous urban planning over the head of the City Council.

Even more alarming are the varied legal exemptions the government uses to circumvent not only the local government, but even its own centralised line of authority.

A key tool in Orban’s hand is a law from 2006, further sharpened during his tenure, on the “easing and hastening of priority investments of national economic relevance”.

Over the past years, investments put under this category included not only high-priority prestige projects such as the new premises of the prime minister’s office on Castle Hill.

The government’s application of the law goes far beyond that scale, and includes by now more than 200 investments (concluded or ongoing) in all of Budapest’s 22 districts. From the refitting of Catholic grammar schools and local sporting venues to the erection of public sculptures, these investments of “national economic relevance” reek of corruption.

In other instances, the government passes separate bills into law that specify certain investments, including their territorial scope, and take them out of normal procedure.

The infamous Liget Project

One such case is the infamous Liget Budapest Project, by now a symbolic point of contention between the city administration and the government.

In 2013 the parliament passed a bill that practically confiscated City Park (Városliget), Budapest’s historic and second-biggest public park, from the municipality of Budapest, and set out to build a modern museum district of five large-scale public buildings in what is according to the government “Europe’s biggest ongoing urban cultural development plan”.

The choice of location and the forced nature of the planning led to public outrage and green activists’ sit-in strikes on the construction site (only to be forcefully dispersed by pro-government skinheads).

The Liget Project was a signature issue in the opposition’s successful municipal election campaign which forced Orban to make some concessions.

After the opposition’s victory he suggested that the government won’t push through investments in Budapest that are not endorsed by the population.

At the same time, the new city administration conceded to the conclusion of the two constructions that were already ongoing at the time, the House of Hungarian Music and Museum of Hungarian Ethnography.

In May 2022 though, at the opening ceremony of the latter, the prime minister interpreted the result of the national elections in April as an endorsement for the continuation of the Liget Project in its original form. He seemed little concerned by the fact that Budapest voted overwhelmingly for the opposition.

The law on City Park is far from being the only legislation that appropriated urban areas in Budapest for the government’s building projects.

Acts on the construction of the Budapest Olympic Centre (2012); on the Normafa Park “historic sporting area” (2013); on the “state’s responsibilities regarding development in Budapest” (2018); a government decision on the appointment of a government commissioner responsible for priority developments (2020) and a government decree on brown field action areas (2021) all specified land where the local government’s normal powers do not apply, and special procedures and “requirements” govern public developments.

Much has been written about democratic decline and the abuse of public funds in Hungary.

Yet, although directly related to EU-law and the principle of subsidiarity, the hollowing out of municipal rights and the diminution of municipal competencies have generated scarce attention in that broader discussion.

Budapest, a large European city with a democratically-minded electorate, and the EU’s only capital led by a green mayor, is being massively developed against its publicly discussed and duly adopted development strategy.

With Viktor Orban’s newly sealed fourth constitutional majority, that tendency will continue.

Source: euobserver.com