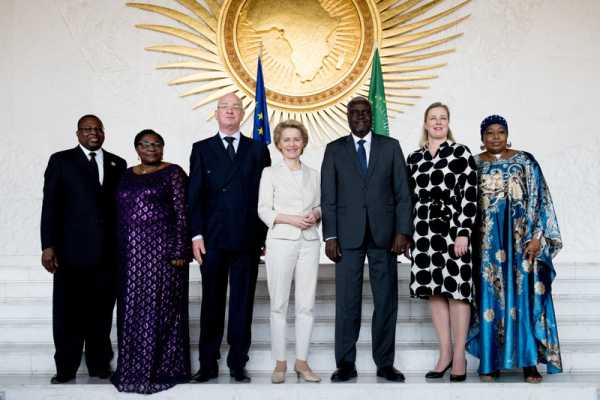

EU Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen (centre) at a previous EU-AU summit in Addis Ababa in 2020 (Photo: European Commission)

This weekend (17-18 February), African leaders will meet in Addis Abada for their 37th African Union summit. European leaders should pay serious attention, in particular those who put the relation with Africa on top of their foreign and development policy, such as Georgia Meloni and Ursula von der Leyen.

At the end of January, over 40 leaders from the African continent met in Rome with the hope to learn more and shape the Italian investment approach to Africa, or “Mattei Plan”.

Italy’s relation with Africa has become Meloni’s largest international foreign policy project and will be the litmus test of her international credibility in 2024.

To her credit, Meloni has elevated this relation to the highest political level. Given the scale of the development challenges faced by African societies, this is exactly the right level to build the political consensus and mandate for much-needed action.

However, little at the scale, quality and inclusivity needed to face the challenge was achieved in Rome. This was certainly only the beginning of an ambitious endeavour, but a lot more remains to be done.

The African Development Bank estimates a gap of over $100bn [€93bn] per year in infrastructure investment in the African continent. At the same time high debt levels, increasing debt service costs and high-interest rates are limiting the investment capacity of African countries for vital social and climate needs.

Since 2010, public debt in sub-Saharan Africa has skyrocketed to $1.3 trillion, private creditors are taking out greater amount than they are investing and the poorest countries in the world — most of which are in Africa — paid $89bn in debt-servicing costs alone in 2022.

None of this daunting reality was recognised by Meloni.

Italy’s offer to mobilise €5.5bn over the next years, overwhelmingly in already-allocated loans and guarantees, pale in comparison to the volumes and reforms needed for the financing challenges faced by Africa. Only an EU-wide coordinated financial offer can credibly respond to African needs.

Italy however has a second chance throughout the year to turn words into action. A major opportunity to increase financial means African nations need hinges on the replenishment of the International Development Association (IDA), one of the most concessional forms of financing of the World Bank whose main beneficiaries are African countries. Upholding and enhancing its grant element and at least sustaining the current level of grants will be crucial.

The Italian G7 presidency of 2024 — which takes place 80 years after the creation of the Bretton Wood Institutions — is another major opportunity for Italy to set out its vision to make the international financial system fit for a fast-warming and still largely unfair world.

Debt moratorium

Supporting debt reforms, a debt moratorium — as asked by the African Union — and mechanisms to increase the fiscal space for productive investment will be key. Again, Italy will need to work with its European allies to provide the scale and depth needed, the more so in a scenario of a US retrenchment under Donald Trump.

Next to debt, the other elephant in the room — as highlighted by Kenyan president William Ruto — is the quality of energy investment.

While recognising the need to address the climate-energy nexus in Africa, Meloni has remained too ambiguous about the nature of energy investment she will support. The summit was a missed opportunity to spell out by both Italian and African leaders how they intend to uphold the COP28 Dubai declaration of transitioning away from fossil fuels.

The powerful influence of the Italian O&G company Eni, the second-largest producer of oil and gas and the third-largest developer of new oil and gas in Africa, cannot be ignored. The more Italian diplomacy and politics remain entangled with O&G industry’s plans misaligned with a science-based transition, the less credibility Italy will gain on the international stage.

Sign up for EUobserver’s daily newsletter

All the stories we publish, sent at 7.30 AM.

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

By supporting new gas projects incompatible with climate, security and development goals, Italy will fail to credibly support a sustainable growth path for African people, who benefit the least from new fossil fuels projects, such as in the case of Mozambique, and to address climate change as a root cause of forced migration.

The World Bank estimates that by 2050 there could be up to 216 million ‘climate migrants’ worldwide, with sub-Saharan Africa affected the most.

Phasing out fossil fuels is a main request of over 70 organisations of African civil society to the Italian and African leaders. However, while the Italian O&G industry representatives enjoyed full access to the summit, there was none provided to civil society nor transparency over the discussions, marking a huge disconnection between public interest and political representatives.

Both in Europe and Africa we need a much more open and inclusive conversation about where the public interest lies in the era of climate change. And how to address the conflict of interests between the fossil fuels industry and decision-making bodies, as it emerged at COP28 and will continue at COP29 in Azerbaijan.

Without accountability, openness and innovation, Meloni’s intention of building a new and fairer relation between nations will fail. There is still time to catch up.

The Italian G7 Summit in June is the next stop which will tell if we are witnessing a real “paradigm shift”, as claimed and hoped by Meloni, or another empty promise.

Source: euobserver.com