The US is once again planning to achieve peace through mineral deals. After Ukraine, the focus is on the conflict between Congo and Rwanda, which has been going on for over 30 years. The Democratic Republic of Congo holds the largest cobalt deposit in the world, which is actually controlled by China. For the Donald Trump administration, this is another lever of influence in the global economy. NYT, The Conversation, Reuters, CSIS and BBC have analyzed what started the military conflict in East Africa and how the US is getting involved in the war for resources

Subscribe for 6 issues of Forbes Ukraine with meaningful interviews, ratings and analytics, now with a 50% discount .

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda crossed the finish line in early May 2025 in a peace deal that could change the balance of power in East Africa. The move is the culmination of months of US-brokered talks that seek not only to end the war between them but also to lay the groundwork for massive Western investment in the region, rich in strategic minerals, Reuters reports.

Washington is moving quickly, as it did with the minerals agreement with Ukraine. Its draft has already been submitted to the parties, and US Secretary of State Marco Rubio is preparing to meet with his counterparts in the African capitals of Kinshasa and Kigali for final approval. It is expected that all documents – both the peace agreement and the accompanying economic agreements – will be signed within two months with the participation of Donald Trump.

Popular Category Money Date May 07 “We will be happy if the US earns $350 billion.” 12 awkward questions for Ukrainian negotiators about the Subsoil Agreement. Interview with the team led by Yulia Svyrydenko

The agreement not only provides for an end to hostilities, but also opens the door for billions of dollars in investment by American and Western companies in the mining industry and infrastructure of Congo and Rwanda. This is one of the strategies of the Trump administration, which is being implemented in countries with unresolved military conflicts. A separate line is written about the creation of new mineral processing facilities in Rwanda, which also has resources, although smaller than in Congo.

However, behind the scenes of diplomatic negotiations is a harsh reality.

Fighting continues, and the humanitarian situation worsens with each passing week. The UN and Western governments have directly accused Rwanda of supplying weapons and taking territory in Congo, although Rwanda itself insists that its forces are acting solely in self-defense against the threat posed by the Congolese army. Despite the diplomatic breakthrough, people are dying every day in eastern DRC and hundreds of thousands are fleeing their homes.

War for resources and influence

The war between Rwanda and the DRC has deep historical roots, dating back to 1994. Then one of the most terrible genocides of the 20th century took place in Rwanda: extremists from the Hutu ethnic group killed about 800,000 people, mostly Tutsis – the opposing ethnic group, writes the BBC. After the Tutsi rebels led by the current Rwandan President Paul Kagame seized power, about a million Hutus, including many involved in the genocide, fled to the territory of neighboring DRC (then Zaire).

The Hutu flight to Congo sharply exacerbated ethnic tensions in the eastern regions, where Tutsi communities already lived. Rwanda considered the presence of “genocide” perpetrators on the border a direct threat and twice sent troops into the DRC under the pretext of pursuing perpetrators of the genocide.

In 1996–1997, the Rwandan army supported a rebellion in Zaire that led to the overthrow of dictator Mobutu Sese Seko and the rise to power of Laurent-Désiré Kabila. However, within a year, Kabila broke off the alliance with Rwanda, allowing the Hutu to regain power in the east.

This triggered a second war, with Rwanda and Uganda again invading the DRC, and Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe on the Congo’s side. These two wars became known in the 1990s as “Africa’s World Wars” and resulted in the deaths of millions.

After the wars officially ended in the 2000s, dozens of armed groups remained in the eastern part of the DRC, fighting for control of resources and influence in the region.

Women wash ore at the Kamilomb artisanal copper-cobalt mine near the town of Kolwezi in southeastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Photo: Getty Images

Groups associated with the Tutsi and Hutu ethnic groups were particularly active. Rwanda continued to intervene, citing the need to protect the Tutsi and fight the FDLR (Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda), a militia composed, among others, of genocide participants. Russia used similar methods in 2014 when it began seizing territory in Ukraine under the pretext of “protecting the Russian-speaking population.”

In 2009, a peace agreement was signed between the DRC government and the Tutsi-led rebel movement. However, in 2012, some of the former rebels, dissatisfied with the non-implementation of the agreements, formed a new group, M23. The name comes from the date of signing of the same agreement, March 23.

The M23 quickly seized large areas of territory, including the strategically important city of Goma. They were accused of war crimes, and Rwanda was accused of supporting the militants with weapons, logistics, and even direct command. Under pressure from the international community, the M23 was driven out of the country in 2013, with some of the militants integrating into the DRC army.

After several years of relative silence, M23 reactivated in 2021, accusing the DRC government of failing to keep promises to protect the Tutsi. In 2022, the group launched a new offensive, and in 2024–2025, with the support of thousands of Rwandan soldiers, it captured the key DRC cities of Goma and Bukavu, as well as the country’s strategic mineral-producing areas, according to the UN and Western governments.

M23 controls a large part of the border with Rwanda, through which coltan , gold and other valuable resources are smuggled to finance the war. The UN estimates that up to 120 tons of coltan, a component needed to make smartphones, are exported to Rwanda every month.

The current conflict between the DRC and Rwanda is not only a matter of ethnic hatred, but also a struggle for control over reserves of cobalt, copper, coltan, gold, and lithium.

The US, China and the EU are competing for influence in the region, as these resources are critical to a future green economy, writes CSIS. Despite attempts to conclude a peace agreement brokered by the US, fighting continues and the humanitarian situation is critical, adds Reuters.

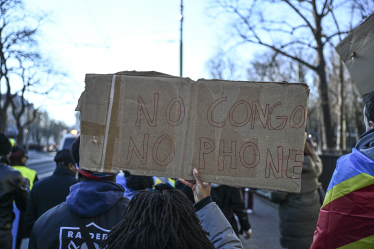

A protester holds a sign reading “No Congo – No Phone” during a demonstration in The Hague, Netherlands, February 1, 2025. The marchers were demanding justice for the ongoing genocide in Eastern Congo, which many attribute to Rwandan intervention. Photo: Getty Images

Mineral jackpot

The Democratic Republic of Congo is the world’s largest producer of cobalt, a key metal for electric car batteries and green energy. Congo accounts for 70% of the world’s cobalt production, The Conversation reports. These resources are a major reason why the US, China and the EU are competing for influence in the region.

China has built a veritable resource empire in Congo over the past 20 years. Through “infrastructure for resources” deals, Chinese companies have gained control of most of the major mines.

In 2016, the American Freeport-McMoRan sold one of these – Tenke Fungurume – to the Chinese company China Molybdenum, and this became one of the biggest strategic defeats of the US in Africa, adds CSIS.

Today, China owns or controls stakes in 15 of the largest mines in the DRC, and 65% of the world’s cobalt for batteries is processed in Chinese factories.

Trucks haul ore from a quarry at the Tenke Fungurume mine, one of the world’s largest copper and cobalt mines, owned by the Chinese company CMOC, in the southeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Photo: Getty Images

The US is trying to change the situation: the Donald Trump administration is offering the Democratic Republic of Congo large-scale investments and security guarantees in exchange for access to resources. Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi directly compares the situation to the war in Ukraine, because it is not only about territory, but also about the future of global supply chains. As in the case of Ukraine, the US acts as a mediator and potential security guarantor, and the issue of peace is closely linked to transparency, reforms and the involvement of Western capital.

However, the DRC’s mineral wealth does not translate into prosperity for the population. More than 74% of the country’s residents live in poverty. The proceeds from mineral extraction are concentrated in the hands of the elite, while the lives of local communities are not improving, writes The Conversation.

Much of the mining industry is artisanal, involving child labor and corruption, and the policies of the Congolese government could directly impact the future global supply chains for batteries and electric vehicles.

In 2022, the DRC government temporarily halted exports from the largest mine, owned by a Chinese company. This immediately cut 10% of global cobalt production, The Conversation adds. Local elites are able to realign international players according to their own interests, and even local elections in mining towns can affect global markets.

As in the case of Ukraine, issues of peace and development are closely linked to access to strategic resources and a country’s ability to defend its interests in the global marketplace.

But for Congo, the situation is more complicated due to China’s influence on mineral extraction, pressure from M23 and Rwanda, and the poverty of mining regions. The country will either become another victim of geopolitical games or become a key player in the global energy revolution, CSIS comments.