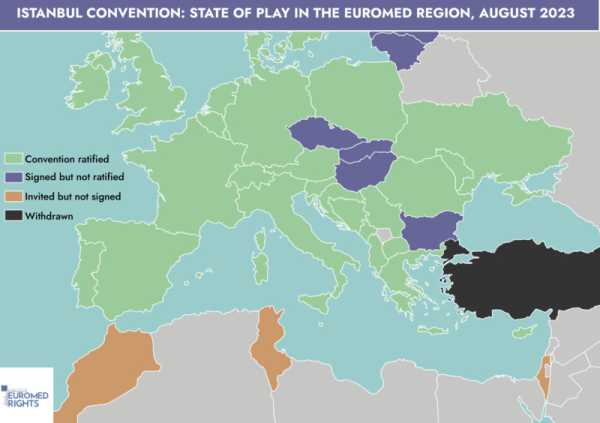

All 27 EU member states have signed the convention — however, only 21 have ratified it (Photo: EuroMedRights)

Tuesday (1 August) is the ninth anniversary of the entry into force of the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, colloquially known as the Istanbul Convention, and with the rise of anti-gender campaigns and movements in the Euro-Mediterranean region, we reiterate the importance of this convention, especially in the current climate of backlash to gender equality in the Euromed region.

Entering into force on 1 August 2014, this convention represents the most advanced international legal instrument to set out binding obligations to prevent and combat violence against women, addressing all forms of gender-based violence against women and girls in all their diversity, including domestic violence. It also offers practical insights on how citizens and NGOs can bring about real change.

The convention uses the term “gender” to reinforce that gender inequalities, stereotypes and violence do not originate primarily in biological differences, but from harmful prejudices about women’s attributes and roles in society.

The growth of anti-gender narratives and campaigns, with far-right parties and movements repurposing the term “gender” to divide and roll back women’s rights and LGBTQI+ advances, is observable across the Euro-Mediterranean region, as reported in our gender backlash map, a tool developed by EuroMed Rights to monitor backlashes to gender equality in the Euro-Mediterranean region.

In the midst of these developments, the Istanbul Convention finds itself, in every sense, ‘caught in the middle’.

In the EU, all 27 member states have signed the convention. 21 have ratified it, however among them, in 2020, the governing political party in Poland (PiS) declared the possibility of withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention entirely to protect children and traditional family values.

Hungary and Turkey refuseniks

In the six member states that have signed but not yet ratified the convention — Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Slovak Republic — some have cited similar arguments to qualify this decision.

Hungary, for example, refused to ratify the convention on the grounds that it promotes a “dangerous gender ideology”, while the Tribunal Court of Bulgaria stated that its ratification would be anti-constitutional.

The clearest enactment of this discourse was the government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s withdrawal of Turkey from the Istanbul Convention in July 2021, claiming that it had been “hijacked by a group of people attempting to normalise homosexuality” and undermine the country’s social and family values.

Tunisia and Israel also

On the southern shore of the Mediterranean, Morocco, Tunisia and Israel have been invited to sign the Istanbul Convention.

However, current governments in Tunisia and Israel have already said that they will not pursue the signature and ratification process.

In the last universal periodic review in 2022, the Tunisian government took note of the recommendations by several countries to ratify the convention, highlighting, however, that the convention contained terms like “gender” or “sexual orientation and gender identity” that were not consistent with the Tunisian reality.

The Israeli government declared in December 2022 that it will not approve the country’s accession to the Istanbul Convention, being concerned about clauses granting asylum to victims of domestic violence.

On this 1 August and in a world where gender-based violence affects one-in-three women in their lifetime, EuroMed Rights reiterates that violence against women and girls is one of the most devastating human rights violations and that the Istanbul Convention remains the most comprehensive legally binding tool to protect and prevent this phenomenon.

Source: euobserver.com