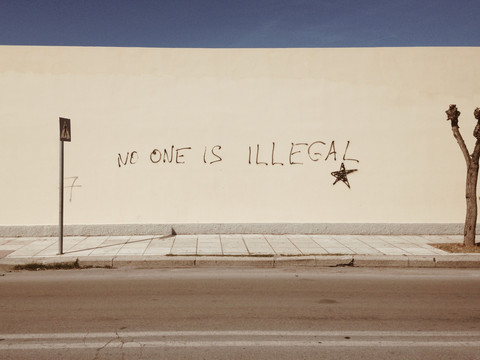

Even before civil society actors started to carry out rescues at sea, state-led rescue operations were ended after being blamed to lead to increased migrant crossings from northern Africa (Photo: consilium.europa.eu)

Whenever I hear the term ‘pull factor’, a sigh escapes my lips. Unfortunately, this occurs several times a day at the moment, given the term’s inflationary use in the many polarised, if not to say hysterical, debates over migration.

The ‘push/pull’ model goes back to the 19th century and the work of Ernest George Ravenstein who sought to develop ‘laws of migration’ that would allow to understand and even predict human migration. Migration scholars have since tried to identify the myriad factors and their relevance in explaining movements between places, including economic, social, demographic, or environmental factors.

-

These days, anything can be constructed as a pull factor. UK prime minister Rishi Sunak recently suggested that children arriving by boat should not be exempted from detention because 'We don't want to create a pull factor…' (Photo: Miko Guziuk)

The problem is that there has never been an agreement on such factors and their specific role in causing migration, prompting geographer Ronald Skeldon to note already in 1990: “The push-pull theory is but a platitude at best.”

As migration scholars Hein de Haas, Stephen Castles, and Mark Miller note in The Age of Migration: “push-pull models are inadequate to explain migration, since they are purely descriptive models enumerating factors which are assumed to play ‘some’ role in migration in a relatively arbitrary manner, without specifying their role and interactions.”

While the ‘push/pull’ model thus fails to capture the complexity of migration projects and dynamics, especially the ‘pull factor theory’ lives on in public discussions over migration where a simplistic theory is further simplified.

These days, anything can be constructed as a pull factor. In the UK, prime minister Rishi Sunak recently suggested that children arriving by boat should not be exempted from detention: “We don’t want to create a pull factor to make it more likely that children are making this very perilous journey in conditions that are appalling.” In, France, a local municipality tried to prevent a charity from installing outdoor showers, fearing they could function as pull factors for migrants.

In Germany, the pull factor discussion took a similarly absurd turn only last week. Friedrich Merz, leader of the Christian Democratic Union, complained about rejected asylum seekers receiving social benefits and getting their teeth fixed in Germany while German citizens were not even able to get dentist appointments.

In the Mediterranean context, pull factor talk has been particularly loud and consequential. Even before civil society actors started to carry out rescues at sea, state-led rescue operations were ended after being blamed to lead to increased migrant crossings from northern Africa. The Italian operation Mare Nostrum fell victim to such pull factor talk in 2014.

In consequence, the rescue gap at sea has widened ever since, with forms of non-assistance becoming systematic, and the death toll rising.

Social media explosion

Once NGO rescuers came onto the scene, pull factor talk exploded.

Pushed by the EU border agency Frontex, many EU member state governments, as well as rightwing groups and trolls on social media, the idea that the presence of rescuers would ‘pull’ people onto these dangerous journeys, and in consequence increase the number of fatalities at sea, took flight.

In order to counteract such accusations, several migration scholars have tried to produce scientific evidence that would show the lack of correlation between NGO presence at sea and figures of migrant departures.

These studies are important and have demonstrated that factors such as the weather and the conditions in countries of departure are much more key in explaining changing migration movements at sea.

Sign up for EUobserver’s daily newsletter

All the stories we publish, sent at 7.30 AM.

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

But still, despite the many attempts to ‘debunk’ them, the pull factor theory proves resilient. Instead of producing further studies to disprove this ‘theory’, we should radically disengage from pull factor talk. Accepting the terms of the debate risks inadvertently legitimising the premise of this ‘theory’.

At the heart of pull factor talk is the denial of agency to those on the move.

It suggests that without rescuers at sea, many would not have migrated in the first place. This could not be further from the truth. For many of those who board dangerous boats, the Mediterranean crossing is only one leg in lengthy and zig-zagging migration journeys during which they are exposed to a variety of harms. They need to decide, again and again, and in unfavourable conditions and changing circumstances, whether to move on, or not.

Those who engage in pull factor talk tend to deny this reality of migration and the subjectivity of people on the move, their own good reasons and needs for taking to the sea and crossing borders, their individual desires and wishes for their futures. In doing so, also the diverse reasons why so many cannot stay where they currently are being denied.

As the scholars Glenda Garelli and Martina Tazzioli note, engaging in pull factor talk is ultimately a trap, a dead end. By reducing migration to seemingly easily discernible factors, it is unable to comprehend the complexity of contemporary migration.

Source: euobserver.com