Consumers, despite seeing benefits in the rollout of AI, had low trust in the use of AI systems respecting their personal data and were concerned it could manipulate their decisions (Photo: Jonathan Kemper)

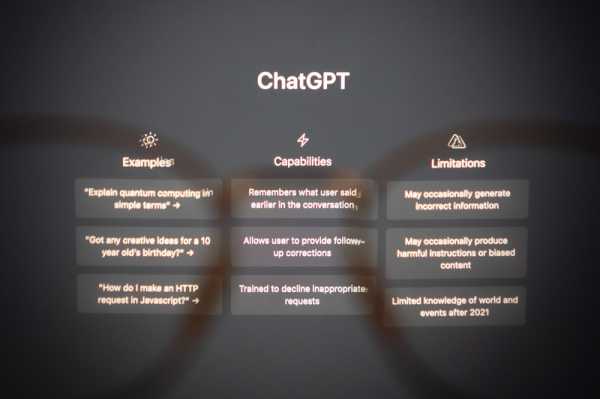

In the last few weeks, the world has been gripped by a remarkable artificial intelligence tool. ChatGPT can generate all types of texts such as essays, media articles, and even poems. It is both fun and fascinating. And yet ChatGPT is also raising difficult questions, with its potential for disinformation giving legislators a headache.

Brussels is currently at a crossroads for dealing with the enormously important questions about the role we see for AI in our society and, importantly, where we need to draw red lines.

-

Consumers also generally don't trust authorities exerting effective control over AI systems (Photo: Jonathan Kemper)

It has been almost two years since the European Commission published draft legislation to regulate AI systems, and discussions in the EU institutions are now reaching the critical stage. The European Parliament will finally set out in the next few weeks what it thinks the AI Act should do.

MEPs have to get it right and protect people from harmful uses of AI systems which could significantly impact our lives as citizens and consumers, and our society as a whole. So far, neither the commission nor national governments have done enough. MEPs must think carefully about how we want to use AI technology in our society, and how we don’t.

Consumers in the hands of AI?

That is because AI systems will soon be doing much more than writing fun or elegant texts the way ChatGPT does.

In the rental accommodation market, Airbnb has already patented AI software that can supposedly predict a person’s traits and their actions based on data it holds on them, for example from social media.

Such an AI system would determine how much a consumer pays, or whether they would even be able to access particular accommodation.

It begs the question of how the consumer could ever know if they were being discriminated against and what criteria were being used to reach this decision. In particular, we should be asking if we want to be subjected to social scoring by businesses at all.

AI is increasingly being used across the insurance industry to calculate how much a premium for car or home insurance will cost, or whether the customer should be offered a policy at all.

The vast datasets that these systems will be able to rely on and analyse at ever faster speeds are likely to lead to more and more personalised prices without us being able to know which factors are taken into account for this personalisation, or to contest the AI’s decision.

AI could have a devastating impact on some people’s personal finances if the data is incorrect or there are negative biases in the algorithm’s reasoning.

In 2021, Frances Haugen revealed how Facebook’s algorithms were causing physical and psychological harm to teenagers by forming addictions and habits. TikTok is being investigated in the US for similar concerns.

These algorithms need greater public scrutiny, and public authorities must reassert control over them if a company doesn’t take remedial action.

The solution: regulate where harm can likely occur.

Sign up for EUobserver’s daily newsletter

All the stories we publish, sent at 7.30 AM.

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Our own survey from 2020 showed that consumers, despite seeing benefits in the rollout of AI, also had low trust in the use of AI systems respecting their personal data and were concerned it could manipulate their decisions. Consumers also generally don’t trust authorities exerting effective control over AI systems.

Over the next few weeks, the European Parliament must step up its ambition and push for effective consumer protection in the AI age.

First, parliament should ban AI systems which carry an unacceptable risk of harm for consumers.

Social scoring by companies, where consumers are commodified as much as the product or service, surely has no place in a society where we value an individual’s right to privacy, autonomy and dignity.

Facial recognition by businesses in publicly accessible spaces, where our faces and every move are detected and scrutinised, should also be forbidden. The commercial value of companies knowing what we do and where we go might be high, but we should be free to go where we want without a company’s cameras and sensors following us. Respect for the fundamental rights of privacy and autonomy must prevail over so-called innovative business ideas.

Secondly, the EU parliament needs to make sure that the scope of high-risk AI systems under the law is broader.

Systems which can cause consumers harm should be included in that category so that they have to meet specific obligations. Content recommender systems, home assistants, smart meters, all retail insurance which uses AI systems, and any AI likely to be used by children, need to be considered high risk.

Thirdly, all other types of AI systems must respect certain broad principles such as fairness, transparency and accountability which are integral to our society. ChatGPT should be no exception. The EU’s AI Act must be a flexible, future-proof, piece of regulation that can also address risks as they arise.

Finally, a technology of this complexity and reach cannot be rolled out without giving strong rights to the people who will be affected by it. Such rights must include a right to object to a decision by an AI system and to receive an explanation, but also to seek redress from the company in case its AI system has caused harm. Importantly, it has to be possible for consumers to go to court as a group to seek collective redress.

The ball is now in the camp of the European Parliament. This new AI law is a great opportunity for the EU to foster and lead on socially valuable innovation. It should ban technology which can cause serious harm. It should put consumers, citizens, and democracies at the front and centre in the AI age. ChatGPT isn’t the only AI application coming our way.

Source: euobserver.com