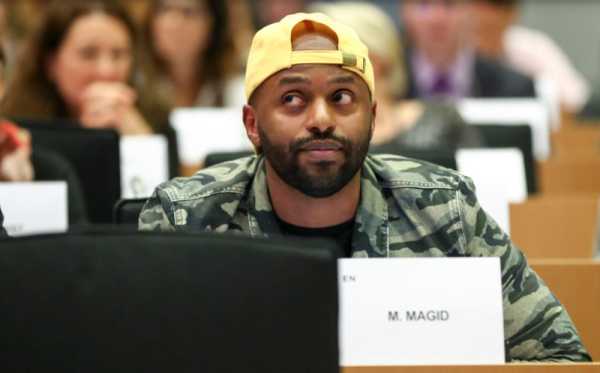

Magid Magid: 'Despite the apparent novelty of the partnerships, they rigidly conform to the broken status quo in the most important respects: being predicated on a loan-based financing system' (Photo: European Parliament)

Unveiled at COP26, the G7-led Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) promised to offer a new model of international cooperation towards decarbonisation — indeed, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, one among the International Partners Group (IPG) of financiers, touted the initial partnership as “a global first [which] could become a template on how to support just transition around the world”.

Yet almost two years on, the sheen has slowly begun to dull on the JETPs, which have thus far been signed by the governments of South Africa, Indonesia, Vietnam and, most recently, Senegal.

-

As the latest green capitalist charm offensive, the JETPs are likely to lead quickly to spiralling 'green' indebtedness, and in turn, 'green' austerity in host countries (Photo: European Community, 2006)

The inaugural signatory, South Africa, is wracked by internal divisions and indecision over the future of their agreement, Indonesia’s plan has been delayed over divisions between the government and financiers, and the Indian government is dragging its feet over a prospective agreement.

And a peek behind the public relations gives good reason to be wary. Despite the apparent novelty of the partnerships, they rigidly conform to the broken status quo in the most important respects: being predicated on a loan-based financing system.

As such, the JETPs represent the messy contradictions at the heart of modern mainstream climate proposals: with IPG members forced to grapple with the reality of climate crisis with one hand, while using the other to rein in the ambitions of climate justice within neoliberal orthodoxies.

South African example

The unravelling of the flagship South African JETP is instructive.

Offered a finance package amounting to $8.5bn [€8.02bn], the JETP centres largely on electricity sector reforms; transitioning away from South Africa’s reliance on coal-generated energy towards privately-generated renewables.

This takes the form of decommissioning coal-fired plants largely in the impoverished Mpumalanga province and ‘unbundling’, or breaking up, the state-owned Eskom electricity company in order to enable greater private energy participation in the system.

Other tenets of the transition include building an electric vehicle industry and developing a green hydrogen sector — in line with recent, and controversial, efforts by European powers to encourage African nations to become exporters of the fledgling fuel source.

Intended as ‘start-up’ finance, the $8.5bn is expected to catalyse further private and philanthropic investment to see through the country’s green transition in the long-term.

To that end, 90 percent of the IPG package is allocated towards the electricity sector reforms in the JETP, largely on infrastructure, while a miserly 0.14 percent ($12m) is allocated to skills development and 0.19 percent ($16m) to social investment and inclusion — raising major questions about the fidelity of the JETP towards its ‘just transition’ objectives.

Yet in May, the South African government moved towards postponing the decommissioning of coal-fired plants to help alleviate chronic rolling blackouts in the country, in the process throwing up question marks over the very viability of the JETP.

Domestic opposition to the partnership has also grown fierce — caused in no small part by the fog of uncertainty that workers in the coal belt face in trying to understand their fates under the JETP.

Sign up for EUobserver’s daily newsletter

All the stories we publish, sent at 7.30 AM.

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

The ruling ANC-led government, meanwhile, has been beset by divisions over the role of coal in South Africa’s economy, with one minister pointedly telling Germany’s vice chancellor that South Africans “didn’t want to be the West’s guinea pig for the global energy transition.”

A closer analysis of the details of the JETP, and South Africa’s implementation plans, should stir anxieties for international observers as much as it has South Africa’s locals.

Some 90 percent of the $8.5bn financing comes in the form of loans, and is largely being disbursed through western development finance institutions whose modus operandi lie in delivering public-private partnerships (PPPs), often alongside their respective national private entities.

The IPG financing itself comes with conditions to restructure policies to enable greater private participation in the energy sector and to build market confidence.

The drive towards privatisation in the JETPs is unmistakable, as are moves to undermine state control over energy assets — reducing the role of the South African state to that of guarantor for private sector adventurism in a new ‘green energy’ sector, and with it, imperilling energy security for the populations most vulnerable to climate change.

In the face of looming climate crises, taking away the ability of states to respond to future crisis-induced energy shortages among their populations stands as remarkably short sighted.

As the latest green capitalist charm offensive, the JETPs are likely to lead quickly to spiralling ‘green’ indebtedness, and in turn, ‘green’ austerity in host countries, threatening to drive a damaging wedge between workers and the energy transition.

The moves towards privatisation in the energy sector are also likely to usher in the attendant risks to workers’ rights, foreclosing meaningful efforts at implementing a ‘just transition’.

It is for this reason that the curious silence of Europe, especially press, workers’ and social movements, on the JETPs stands out as particularly concerning.

The JETPs offer a glimpse into emerging climate policy paradigms, reflecting the many faultlines of modern climate justice — from the battles over the meaning of ‘Just Transition’ to the centrality of solidarity with the Global South — which will soon be fought out nearer to home.

Source: euobserver.com