Ursula von der Leyen’s unofficial bid to keep the European Commission’s top job started off with the flash of an anti-subsidy probe and a bang of exhortations to bring Ukraine, Moldova and Western Balkan countries into the fold. What she sidestepped was how to find more cash and convince member states to pay up.

Without credible plans to raise more money, the European Union won’t be able to build a strong future.

The war on the bloc’s eastern border has raised the stakes. Midway into the second year of war after Russia’s invasion, Ukraine needs $411 billion in reconstruction funds, according to World Bank estimates, while the Commission sees a 110 billion euro funding gap between now and 2027. It’s unclear where the money will come from. The EU’s 1.8 trillion euro seven-year budget, drawn mainly from national contributions and customs taxes, is already stretched thin.

While the bloc was able to agree on €800 billion in historic joint borrowing during the pandemic, Brussels has so far failed to make its public debt capacity permanent, let alone lining up new sources of revenue. Proposals to raise even a modest amount of new “own resources” – dedicated funds that go straight to the EU coffers – have fallen flat. A trio of measures proposed in December 2021 has gone nowhere and in any case would add only €17 billion of revenue a year, even at full strength. A similarly sized proposal put forward in June appears equally stuck.

Whoever leads the Commission once von der Leyen’s current term ends in mid-2024 will thus face budget woes that, if not addressed, risk putting the entire EU project in jeopardy. Yet budget concerns will be hard to discuss honestly during the byzantine process to pick a head for the powerful EU executive.

The head of the European Commission is not directly elected. Candidates generally need to win the support of their own political party group – be it the Liberals, von der Leyen’s own Conservatives, the Socialists or the Greens – then engage with the European Parliament, which holds elections in mid-2024 across the EU, and wade through member states’ machinations on how the plum jobs get handed out.

Unusually, the 64-year-old von der Leyen owes her first term not so much to her home country of Germany, or even her political party, as to support from French President Emmanuel Macron, who aligns with the EU Liberals. It remains to be seen if he will back her for a second term or push for a national wild card like industrial policy commissioner Thierry Breton, whose brash support for corporate handouts has proven both charismatic and divisive. Further muddying the waters, von der Leyen herself could be in the running to succeed Norway’s Jens Stoltenberg at NATO, whose term has been extended to October 2024 because member countries have not agreed on who should replace him.

Von der Leyen, or her successor, will have to figure out how to pay for enlargement. Ukraine became an official EU candidate alongside Moldova and Bosnia and Herzegovina, joining Montenegro, Serbia, Albania and North Macedonia in the EU’s accession purgatory. Kosovo is waiting in the wings. Turkey and Georgia are also in the accession queue, albeit with lesser prospects. Joining will require new entrants to pledge improvements on core issues like the rule of law, human rights and democratic accountability. It will also cost money.

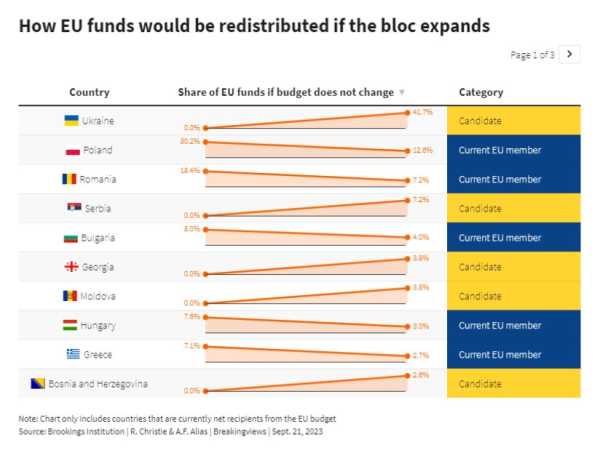

And if the union gets bigger, countries accustomed to being net recipients of EU funds might suffer. A report by the Brookings Institution’s Carlo Bastasin predicted that some EU members would face huge cuts if the newcomers join and the overall budget does not expand. Spain, for example, would see its share of EU financial aid go from nearly 10% to zero. Poland, which receives nearly a third of those funds, would see that portion plummet to 13%.

The EU also needs to finance the transition to a “greener” economy, and to keep up in what could become a global subsidies race with the United States and China. Von der Leyen tapped into trade frustrations with her pledge to investigate and possibly punish Chinese subsidies for car and battery makers. But tariffs can’t close the EU’s investment gap with other major economic blocs, especially given its struggle to match fresh US handouts in last year’s Inflation Reduction Act.

During her first term, von der Leyen succeeded in connecting the EU with bond investors via the €800 billion NextGenerationEU borrowing programme. A former physician and German defence minister, her strategy is generally to stake out a broad policy position while leaving plenty of wiggle room to make concessions to member states. A second term will require even more finesse to convince EU member states to raise money not just from markets, but from themselves.

Of the existing dormant proposals, the most practical one is a revamp of corporate taxation that could raise €4 billion annually and would bring the EU into better compliance with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s global tax deal. The EU hopes its 12 September relaunch will find a path forward if budget needs can convince sceptics like Ireland and the Netherlands to reconsider their longstanding opposition, given that tax matters require unanimous approval from member states.

For more impact, the EU could remove exemptions on aviation and maritime fuel levies, which could have raised €34.2 billion in 2022 alone, according to the clean energy lobby group Transport & Environment. Even if the EU split proceeds with member states, who collect most taxes at the national level, such changes would still bring in substantial new funds.

Enlargement is the biggest carrot in the EU’s neighborhood policy pantry, even if timelines are vague and prone to decades of delay. In addition to considering financial implications, the EU will want to take a tough stand with prospective new entrants on the rule of law, both domestically and with regard to rules set out from Brussels to avoid more standoffs like current battles with right-wing governments in Hungary and Poland.

For any of these accession bids to succeed, existing EU members will need new deals on how decisions are made, how countries stack up to their peers and how on earth Europe will pay for it all. Whether von der Leyen stays or a new leader takes over, they won’t be able to just exhort European values and hope for the best. They will need a plan that brings in money.

Read more with EURACTIV

Osman Kavala wins Europe rights prize, Ankara calls the award ‘unacceptable’The Council of Europe on Monday (9 October) awarded its top rights prize to jailed Turkish philanthropist Osman Kavala, who has come under repeated attack from President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Source: euractiv.com