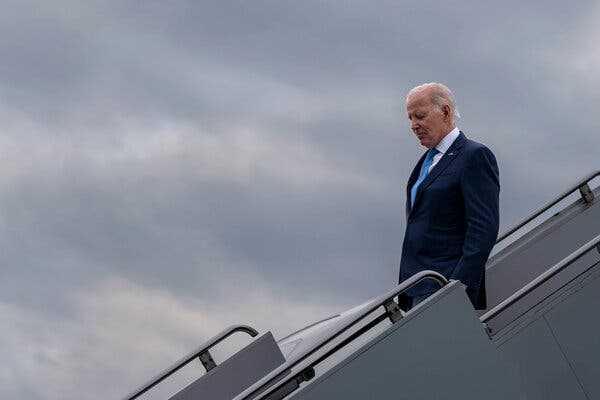

President Biden partly built his political identity around organized labor, which was crucial to his 2024 victory. But changes in union membership mean that he still has work to do.

- Give this article

President Biden’s 2024 re-election campaign is being endorsed by a labor movement that is far younger and more diverse than it has been during his decades in politics.

The public image of President Biden’s “Union Joe” persona rests largely on his longtime affiliations with labor unions representing police officers, firefighters and building-trade workers.

But the modern labor movement that is gathering Saturday in Philadelphia to endorse Mr. Biden’s 2024 re-election campaign is younger, more diverse and has far more women than the union stereotype Mr. Biden has embraced during the decades he was building his political identity.

“You think about it as the dude with a cigar, and it’s just not that,” said Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers. “I’m sure there’s still dudes with cigars, but there’s lots and lots and lots of other people in a multigenerational, multiracial cacophony of people that are unified by a zealous fight for a better life.”

While today’s labor movement is demographically more in line with the Democratic Party, increasing the share of young people and people of color means that union members may be less familiar with — and more skeptical about — Mr. Biden’s record.

The Biden campaign and the labor leaders endorsing it — the A.F.L.-C.I.O. and 17 other unions — celebrated the early backing as a triumph of labor unity for the president.

Julie Chávez Rodríguez, the Biden campaign manager, called it “an unprecedented show of solidarity and strength for our campaign.”

Coming less than two months after Mr. Biden launched his re-election bid, the endorsement reflects not only Mr. Biden’s popularity among the unions’ leaders, but also the reality that a large part of the union membership doesn’t associate Mr. Biden with the union-friendly legislation he has signed into law.

“There is a disconnect between all the Biden-Harris accomplishments and what information is landing on the ground in communities,” said Liz Shuler, the president of the A.F.L.-C.I.O. “It is such an inside-the-Beltway thing to do to talk about policies and talk about legislation and regulations. It’s up to us to decode that and connect the dots back to what is happening in Washington.”

Before he was president, Mr. Biden was a regular at Labor Day parades — especially in Pittsburgh, home of the largely male and white steelworker unions that built much of western Pennsylvania, and where he kicked off his 2020 campaign.

That run followed a defection of large numbers of union workers to Donald J. Trump’s 2016 campaign, which had reoriented the Republican Party in opposition to international free trade accords championed by Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton.

That helped Mr. Trump shave off traditionally Democratic union voters. When Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 presidential election, she won just 51 percent of votes from union households, while Mr. Trump won by huge margins among white working class voters, according to exit polls at the time. Four years later, Mr. Biden took 56 percent of votes from union households, and union voters made up a slightly larger share of the electorate.

“The labor movement is changing, no question. We are having a younger and more diverse work force,” said Lee Saunders, the president of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. “We are seeing a revitalization among young people and people of color who see that they’re being mistreated and they don’t have a true seat at the table.”

Mr. Biden and his administration have been more vocal than his Democratic predecessors in encouraging union organizing. Mr. Biden has welcomed to the White House the millennial Amazon and Starbucks organizers who unionized parts of those companies.

Martin J. Walsh, Mr. Biden’s first labor secretary who is now the executive director of the pro hockey players’ union, said the early endorsements from organized labor were clear attempts to give union leaders more time to press Mr. Biden’s case to their members.

“Having so many unions coming out so early in the process tells you that the unions are solidifying their membership early and working their members early, so they don’t have a repeat of what happened in 2016,” Mr. Walsh said.

Among the youngest labor leaders is Roland Rexha, the secretary-treasurer of the Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association, which represents maritime workers including employees of the Staten Island Ferry. Mr. Rexha, who at 41 is the youngest member and the only Muslim on the A.F.L.-C.I.O.’s executive council, said it can be difficult to sell Mr. Biden to a group that was about three-quarters white men — a group with whom Mr. Trump has drawn majority support.

“Most labor unions do a good job of trying to explain to the members why they need to support the people that support them,” Mr. Rexha said. “It’s something that as leadership, we have had a hard time sometimes relaying to them.”

The broad union endorsements for Mr. Biden Saturday mask some discontent for the president among organized labor. The United Auto Workers has withheld an endorsement over concerns about the electric vehicle transition the White House has championed. There was significant grumbling among labor groups that on the day Mr. Biden launched his campaign, he spoke to the building trades union — a group whose members are seen within the labor world as less reliably Democratic.

And then there is the fact that Mr. Biden’s much-touted infrastructure legislation will largely benefit construction workers — a group far more likely to be male and to vote Republican than the rest of the organized labor universe.

“There is some real progress, ironically, for construction workers, probably half of whom voted for Trump twice,” said Larry Cohen, a former president of the Communications Workers of America who has long been an adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

“The messaging is as good as it’s ever been in 50 years or more, but there needs to be results.”

Reid J. Epstein covers campaigns and elections from Washington. Before joining The Times in 2019, he worked at The Wall Street Journal, Politico, Newsday and The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- Give this article

Source: nytimes.com