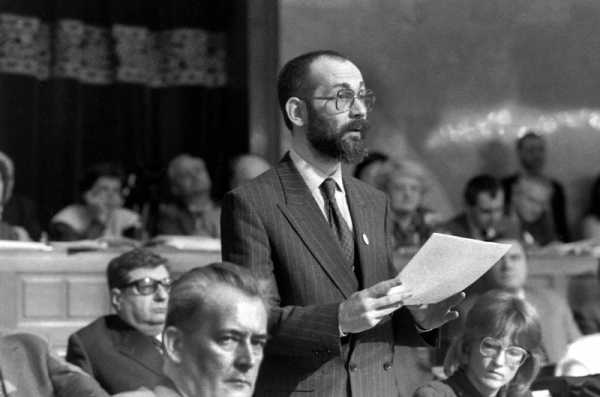

Gáspár Miklós Tamás speaking at the Hungarian parliament in 1990 (Photo: Fortepan / Urbán Tamás)

After the 1989 transition from state socialism to market economy, Hungarians were told — just like the working classes in Western democracies — that there was no alternative to the combination of free market capitalism and liberal democratic institutional politics. But one man, who passed away last month, painted a different path.

Many who had opposed the socialist regimes of Eastern Europe were hopeful that a new free society would arise that could remedy the social and political ills — such as lack of private property, and political rights — of the previous system.

The transition did not realise these hopes.

In many ways, it failed. And by the 2010s the political void left by privatisation and liberalisation of the economy gave rise to a new right-wing hegemony led by Viktor Orbán — the same Orbán who was a young liberal leader in the ’90s.

Back then, Gáspár Miklós Tamás, a Hungarian philosopher, politician, and public intellectual, was often on the same side of the barricades as Orbán. On the 15 January 2023, the day Tamás passed away at the age of 74, the prime minister referred to this shared past when he remembered him as an “old freedom fighter”on social media.

Over time they had shifted to complete opposite ends of the political spectrum. During the first Orbán government in the early 2000s, Tamás foresaw the outlines of an emerging political system, that of post-fascism.

Tamás, who was born in Cluj, Romania and moved to Hungary in 1978, was one of the most recognisable members of the anti-communist opposition in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In fact, he was perhaps the only liberal politician at the time of the regime change who later was able to reflect on the dire socio-economic consequences of the transition itself, the economic and personal traumasit had caused throughout the old socialist bloc.

Leaving professional politics, Tamás eventually returned to academia. And as he turned sharply to the left ideologically, he kept participating in public affairs. He became a subversive polemicist and later a key figure opposing the Orbán regime’s authoritarian measures. He stood up against the racist treatment of refugees and the Roma population and the expulsion of the Central European University to the widespread vilification of homeless people.

Tamás also gave direction to a new generation of left-wing activists and thinkers, who oppose Orbán’s autocratic far-right politics, but also reject the liberal economics and opportunism of many of Hungary’s current opposition, left-wing parties. Without this radical left turn of “TGM” (as he is colloquially referred to) in the early 2000s, a younger generation would not find itself in the same political communities or ideological space where they are today. With his help, we found a political home.

Although he was deeply pessimistic about the future and had a scathing attitude towards current affairs as well as contemporary pop culture, he became the embodiment of the idea that there is an alternative. Even if the institutions of traditional organising are weak, and the real Hungarian left, as he called it, is mostly “informal little groups” lacking in political power, he argued that the possibility of change must be maintained. Not because all those who are active in the left-wing political space in Hungary pursue the exact same aims, but because there is a shared political history and a shared recognition of the challenges ahead.

TGM had a deep personal understanding of what being in left-wing opposition meant: his parents were part of an illegal communist resistance. He knew extensively about the history of the workers’ movement, and he was a selfless teacher spending hours in the last years of his life with young people curious about the struggles of earlier generations of socialists. He was a theorist, but also a historian of the Left. Thanks to him, the contemporary Left must be aware that there have been others who founded left-wing associations under worse circumstances than the current right-wing hegemony in Hungary. Moreover, Tamás was an embodiment of a personal, emotional link to this forgotten past.

He was adamant that the Left should aspire beyond the promises of a traditional welfare state, to struggle for a society beyond the capitalist world-order. However, it was also because of him that we could appreciate that social institutions are not simple facts of our lives. Things like universal health care, social care, or free education (all currently under attack by the Orbán government) are the shared wealth of the Hungarian people for which hundreds and thousands have fought for, and now it is upon us to protect them from market forces and austerity.

Sign up for EUobserver’s daily newsletter

All the stories we publish, sent at 7.30 AM.

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Many will remember his dedication to public life through his journalistic work. Even though he was no less disillusioned than any of us with the political performance of the Hungarian elites, he constantly wrote op-eds confronting the destructive policies of the Orbán-regime as well as the hypocrisy of the opposition, especially the remnants of the old left.

For some it seemed as though he was upholding impossible moral standards in the face of real political developments, while others might have found his way of self-expression dated or elitist. Nonetheless, his work helped connect the fragmented Hungarian left as we all read his essays and listened to his speeches at demonstrations.

The last time I saw him was at an event of Szikra, a new left-wing movement, this summer. We had a cheap canteen lunch and a beer, and then he lectured for about an hour, analysing the historical defeat of socialism. “The left may be defeated, but it’s not dead, as long as there are people who continue to take its cause seriously,” he said.

Perhaps, that’s the best any of us on the Left can do today, to maintain the possibility that there is an alternative.

Source: euobserver.com