To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Media caption,

Watch: Ukraine's recapture of Kherson, in under a minute

By Paul KirbyBBC News

When Vladimir Putin sent up to 200,000 soldiers into Ukraine on 24 February, he thought he could sweep into the capital Kyiv in a matter of days and depose the government.

Russian forces quickly captured big stretches of territory but failed to encircle Kyiv.

Yet in the coming months they were forced into a series of humiliating retreats, first in the north and now in the south. To date, they have lost more than half the territory seized at the start of the invasion.

What was Putin's original goal?

Even now, Russia's leader describes the biggest European invasion since the end of World War Two as a "special military operation" rather than the full-scale war that has left millions of Ukrainians displaced inside their country and beyond.

Sending troops into Ukraine from the north, south and east on 24 February, he told the Russian people his goal was to "demilitarise and de-Nazify Ukraine". His declared aim was to protect people subjected to what he called eight years of bullying and genocide by Ukraine's government – claims which have no basis in evidence. It was framed as an attempt at preventing Nato from gaining a foothold in Ukraine. Another objective was soon added: ensuring Ukraine's neutral status.

High on the agenda was toppling the government of Ukraine's elected president. "The enemy has designated me as target number one; my family is target number two," said Volodymyr Zelensky. Russian troops made two attempts to storm the presidential compound, according to his advisor.

It didn't add up

Repeated Russian claims of Nazis and genocide in eastern Ukraine were completely unfounded but they have formed part of a narrative repeated by Russia since its proxy forces seized parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions in the east of the country in 2014, triggering a war with Ukrainian forces. "It's crazy, sometimes not even they can explain what they are referring to," complained Ukraine's foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba.

An opinion piece by Russian state-run news agency Ria Novosti in early April made clear that "denazification is inevitably also de-Ukrainisation" – in effect erasing the modern state of Ukraine.

It was published as details emerged of war crimes committed by Russian forces against civilians in Bucha, near Kyiv. An independent report later accused Russia itself of state-orchestrated incitement to genocide.

As for joining Nato, even before the invasion Ukraine reportedly agreed a provisional deal with Russia to stay out of the Western defensive alliance. Russia does not want its neighbour to join Nato, as it fears this would encroach too closely on its territory.

By March, President Zelensky had publicly accepted joining Nato would not happen: "It's a truth and it must be recognised." Ukraine offered to become a non-aligned, non-nuclear state, but negotiations broke down.

- In Kherson: Joy, tears and talk of justice

- Medics in the line of fire

How Putin changed his war aims

A month into the invasion and it was clear Russia's campaign was not going to plan. Vladimir Putin dramatically scaled back his ambitions, declaring the first phase largely complete.

The military pulled back from around Kyiv and Chernihiv and regrouped in the north-east. The main goal was now the "liberation of Donbas" – broadly referring to Ukraine's two industrial regions in the east of Luhansk and Donetsk.

The reason for the withdrawal was a failure to appreciate the agility of Ukrainian forces or to secure supply lines. An early symbol of Russia's poor logistics was a 64km (40-mile) armoured convoy that ground to a halt near Kyiv.

Russia's most recent retreat from the southern city of Kherson on 11 November was also down to destroyed supply lines and disrupted command systems, according to Ukraine's commander in chief, General Valeriy Zaluzhny.

Image source, OLEG PETRASYUK/EPA-EFEImage caption, President Volodymyr Zelensky (R) visited Kherson within days of Ukrainian forces liberating it from Russian occupation

Russian proxy forces had already seized a third of Donbas in 2014 in a war that had since turned into a largely frozen conflict. By late March they had claimed most of Luhansk but little more than half of Donetsk.

Capturing the devastated port city of Mariupol in Donetsk in mid-May gave Vladimir Putin one of his few big victories and provided Russia with a much-needed land corridor from the border to Crimea, the Ukrainian peninsula seized by Russia in 2014.

Russian forces still had hopes of seizing further territory in the south. A leading general had previously talked of land grabs along the Black Sea coast beyond Odesa towards a breakaway region of Moldova. "Control over the south of Ukraine is another way out to Transnistria," said Maj Gen Rustam Minnekayev.

By early July, Russia's leader was also able to claim full control of Luhansk, as Ukrainian forces lost as many as 50 to 100 soldiers a day to Russia's overwhelming firepower.

- Tracking the war in maps

Putin on the backfoot

But the arrival of Western artillery, particularly American Himars missiles, soon took its toll on Russia's logistics hubs and arms depots in the east and an anticipated Ukrainian counter-offensive in the southern region of Kherson was also under way.

In September, Vladimir Putin announced a "partial mobilisation" of some 300,000 troops with the aim of bolstering a 1,000km (620-mile) front line in the east. Russians fled the call-up in droves as the war came closer to home.

On the backfoot, he declared that the two eastern regions and two others in the south – Kherson and Zaporizhzhia – were being annexed, even though none was fully under Russian control. They would be part of Russia forever, he said.

Image source, Getty ImagesImage caption, Vladimir Putin addressed crowds in Moscow, with the words "Together forever" at the top of the screen

Weeks later, Russia retreated from Kherson city, the only regional capital seized in its 2022 war.

Under a newly appointed commander, Gen Sergei Surovikin, Russia switched its strategy in October to destroying Ukraine's civilian infrastructure, destroying or damaging 40% of its power system with air raids across the country. It had failed on the battlefield, so now the Kremlin's aim was to target civilian morale.

Cities across Ukraine have been hit, and two people were killed in Poland after a missile landed on a farm close to its border with Ukraine. The incident raised fears of Nato being dragged into the conflict, although the US said it was unlikely the missile had been fired by Russia.

Russia's big failures

The loss of Kherson city and the retreat of 30,000 Russian troops from the right bank of the River Dnipro capped a catalogue of Russian battlefield setbacks that add up to a broad picture of an invasion mired in failure.

The withdrawal from near Kyiv and from Chernihiv in March was followed by a dramatic retreat in early September from the north-eastern Kharkiv region, abandoning the big road and rail hub of Kupyansk and the strategic town of Izyum.

By late September, Ukrainian forces had also liberated another big hub, Lyman, four months after Russia had captured it.

The failures extended beyond the battlefield. Ukraine achieved a symbolic victory with the sinking of the Russian navy's flagship Black Sea battle cruiser the Moskva in April. Weeks later Russian forces were forced to flee the tiny Snake Island outpost in the Black Sea.

Crimea too has seen big Russian setbacks. In early October an explosion badly damaged a bridge across the Kerch Strait, erected after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. That devastating strike on Russian supply lines was later followed by a Ukrainian drone attack on Russia's Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol.

Although President Putin has sought to distance himself from such failures, his own authority appears damaged internationally.

After the drone attack on the Russian fleet, the Kremlin suspended its support for a Turkish-brokered deal for grain ships to sail safely through the Black Sea.

But when the UN and Turkey decided to continue with the shipments regardless, President Putin lifted the suspension. As Germany's foreign minister observed, the international community had refused to be blackmailed.

Has the invasion failed?

By most measures, Russia's war is failing but it still controls all the territory seized in 2014, as well as the coastal corridor from Crimea to the Russian border.

President Putin's partial mobilisation is yet to make a substantial difference on the ground.

For months Russian forces have sought to capture the Donetsk town of Bakhmut and have made some minor gains near by, but it is an indication of the extent to which their ambitions have diminished.

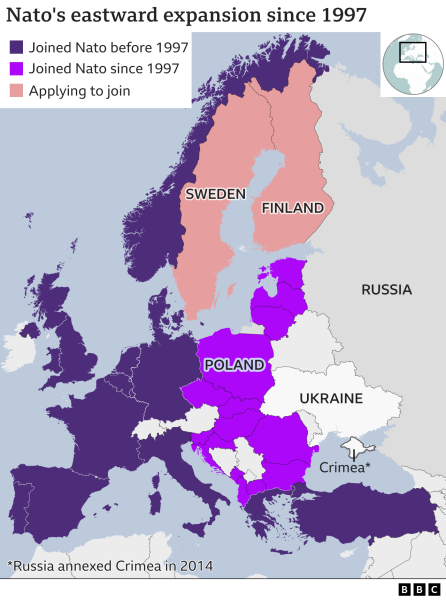

And if the Russian leader's aim really was to push Nato back, that too has failed because Sweden and Finland have applied to join, alarmed by Moscow's military threat.

How Putin's messaging has changed

For years, the Russian president has denied Ukraine its own statehood, writing in a lengthy 2021 essay that "Russians and Ukrainians were one people" dating back to the late 9th Century.

That message was repeated in his two pre-war addresses, in which he accused Kyiv of trying to root out the Russian language and Nato of trying to gain a foothold in Ukraine. He later condemned his neighbour as "anti-Russia".

By September, it was the West that was to blame for trying to "weaken, divide and ultimately destroy our country" while it was Kyiv's fault for its "ambition to possess nuclear weapons".

In reality it was an independent Ukraine that agreed to hand over all the nuclear weapons on its territory when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

Meanwhile, President Putin made a succession of nuclear threats, talking of using all means at his disposal to protect Russia and cling on to its occupied territories.

"We will certainly make use of all weapon systems available to us. This is not a bluff," he warned.

Is Nato to blame?

Nato member states have increasingly sent Ukraine air defence systems to protect its cities as well as missile systems, artillery and drones that have helped turn the tide against Russia's invasion.

But it is not to blame for the war and it was, after all, Russia's invasion that persuaded Sweden and Finland to apply formally to join the military alliance. When Russia said it was annexing four Ukrainian provinces in late September, Ukraine also said it was seeking fast-track Nato membership.

Blaming Nato's expansion eastwards is a Russian narrative that has gained some ground in Europe. Before the war, President Putin demanded Nato turn the clock back to 1997 and remove its forces and military infrastructure from Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Baltics.

In his eyes the West promised back in 1990 that Nato would expand "not an inch to the east", but did so anyway.

- What is Nato and how is it helping Ukraine?

That was before the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, so the promise made to then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev only referred to East Germany in the context of a reunified Germany.

Mr Gorbachev said later that "the topic of Nato expansion was never discussed" at the time.

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Media caption,

Watch: Sweden and Finland formally submit Nato applications

It is Nato's collective defence promise that worries President Putin most. Russian forces first invaded neighbour Georgia in 2008 and then sent troops into Ukraine six years later.

Nato maintains it never intended to deploy combat troops on its eastern flank, until Russia annexed Crimea illegally in 2014.

-

Sweden and Finland's journey from neutral to Nato

- 29 June

-

What sanctions are being imposed on Russia?

- 30 September

-

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline and the crisis

- 29 September

Source: bbc.com