Bosnian football fans fly the flag (Photo: Brad Tutterow)

In June 2022, the European Council announced its possible willingness to upgrade Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) from ‘potential’ to full candidate status, and invited the EU Commission to review BiH’s progress.

The commission having done so, the issue now returns to the leaders’ table in December. Several countries have indicated their support for taking the step. However, it should not be done lightly, as it might well send the wrong message altogether.

-

The dispute and troubled land (Photo: Wikimedia)

Surely, nobody entertain illusions that the council’s aim is anything other than geopolitical. No objective basis exists for going ahead.

After BiH applied for membership in 2016, the commission published a detailed and damning ‘avis’ [judgement] in 2019, failing BiH on all criteria. The commission listed 14 key points — amounting to deep constitutional reform — to address before full candidate status could be granted.

Although the latest avis refrains from drawing conclusions, careful reading shows that precious little progress has happened.

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index for 2021 ranks BiH as a ‘hybrid regime’, the only European country not to merit even the ‘flawed democracy’ label.

Most critical is BiH’s system of ethnic discrimination.

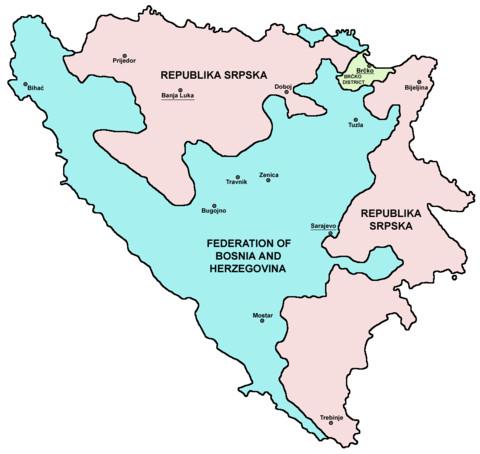

The 1995 Dayton Peace Accords, which have governed BiH since 1995 instituted an elaborate power-sharing system between the three main ethnic groups — Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats.

Belonging to one of these ‘constituent peoples’ is a formal precondition for holding several public offices, including place in the national presidency and the parliamentary upper chamber, and informally determines a person’s prospects for positions in the civil service.

‘Others’

Those citizens outside the three main ethnicities number approximately four pecent of the total population, and are, rather odiously, referred to as ‘the others’.

Such practices was one thing while ending a war in 1995; their continued existence in the 21st century is clearly unacceptable.

In 2009, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) found in favour of two plaintiffs — one Roma, the other Jewish — who argued that the BiH constitution violated their basic human and political rights. The EU froze ratification of BiH’s Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) until the country’s constitution was amended into line with the ECHR ruling (and the EU’s values, as stated in article two of the EU treaties).

Nothing ever happened.

Not that BiH’s constitution is technically difficult to change, because it is not. Rather, the political will is non-existent in a system dominated by ethno-nationalist parties, all of whom benefit from the status quo.

In 2015, after significant lobbying from new member Croatia, the EU decided to ratify the SAA but make the constitutional change a condition for candidate status. That was also the commission’s line in 2019.

The fact remains, though, that the EU has already backed down once on the issue of ethnic discrimination and human rights, and several members of the Council now seem prepared to do so again.

Sign up for EUobserver’s daily newsletter

All the stories we publish, sent at 7.30 AM.

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

One should carefully consider the message that sends. Bosnian ethno-nationalists — who largely retained their power in the recent parliamentary and presidential elections — will achieve a symbolically important and domestically popular victory without meeting the required conditions.

Essentially, the EU will reward defiance of the ECHR. Can it do so again without losing credibility? What will happen, say, when in three years BiH demands actual negotiations, while still maintaining its ethnic quota system?

It is a very slippery slope.

What the EU needs to do before entertaining BiH’s promotion to candidate status is two-fold.

Hungarian ‘bromance’

First, get its own house in order, and put an end to its most irresponsible members undermining the EU’s overall stance. Hungary’s Viktor Orban has developed quite a bromance with Serb leader Milorad Dodik, who looks set to take office as Republika Srpska president despite credible allegations of voting fraud in the recent elections.

Croatia, since 2016 governed by the nationalist HDZ party, has been egging on their BiH sister party in their quest to further divide the country and entrench the ethnicity-based governance system.

This state of mixed messages is clearly untenable. Both countries are major recipients of EU funding, which could be leveraged against them, and bring them back into line with agreed positions.

Second, the EU must bring the Office of the High Representative (OHR) under control. Aside from having extensive decree powers, the OHR can serve as a bully pulpit, and should serve to encourage reform.

Yet, for most of his time in BiH, high representative Christian Schmidt, a German former minister of agriculture, has seemed rather out of his depth, and seemingly reliant on the Croatian government’s advice on Bosnian matters.

In a controversial move on election night, Schmidt made several changes to election laws, which many argued would favour the Bosnian HDZ party.

Whether or not that is so, the biggest problem with Schmidt’s action was the attempt itself to fix or improve a discredited system. By his actions, Schmidt entrenched the system that Bosnia and Herzegovina should seek to move beyond.

The EU will do Bosnia and Herzegovina no favours by moving them forward on a candidacy track that they are not prepared for and itself no favours by abandoning its own values. BiH’s European path has been clear since 2003, but it remains for the country to embrace it.

Source: euobserver.com