In arguments in a voting rights case, the new justice said history must inform constitutional interpretation, making a liberal case for an idea often associated with conservatives.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this articleGive this articleGive this article

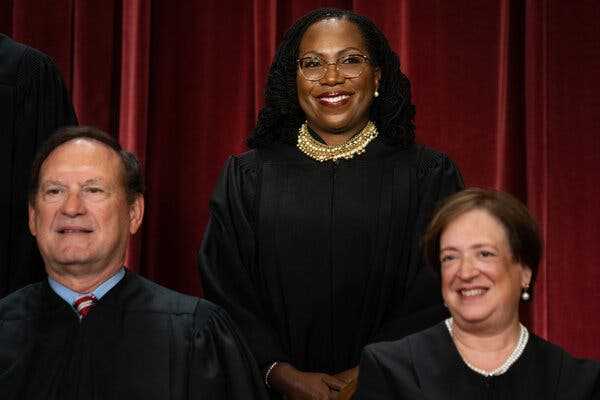

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, center, demonstrated in her second day of hearing arguments on the Supreme Court that she believes originalism can require liberal outcomes.

WASHINGTON — At her confirmation hearings in March, Ketanji Brown Jackson declared herself to be an originalist, meaning, she explained, that she would interpret the Constitution based on how it was understood at the time it was adopted.

“I look at the text to determine what it meant to those who drafted it,” she said.

Conservatives were pleased she had said this, but some wondered whether she had meant it. On Tuesday, during her second day of hearing arguments as a member of the Supreme Court, Justice Jackson demonstrated that she was serious — and that she believes originalism can require liberal outcomes.

She spoke during an argument over the meaning of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a civil rights landmark. The immediate question in the case was whether a congressional map drawn by Alabama lawmakers had violated the act by diminishing Black voters’ power.

But a larger question loomed in the background: Was the act itself in tension with the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, which was adopted after the Civil War?

Many conservatives say the clause forbids the government from drawing distinctions based on race — that the Constitution is colorblind. That was a misreading of the historical evidence, Justice Jackson said, which demonstrated that “the entire point of the amendment was to secure rights of the freed former slaves.”

“I don’t think,” she said, “that the historical record establishes that the founders believed that race neutrality or race blindness was required.”

A week before Justice Jackson’s remarks, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. gave a speech at Catholic University’s Columbus School of Law. His topic was “originalism and the Catholic intellectual tradition,” and he noted that “originalism has often been thought, correctly or incorrectly, to be associated with conservatism.”

Understand the Supreme Court’s New Term

Card 1 of 6

A race to the right. After a series of judicial bombshells in June that included eliminating the right to abortion, a Supreme Court dominated by conservatives returns to the bench — and there are few signs that the court’s rightward shift is slowing. Here’s a closer look at the new term:

Legitimacy concerns swirl. The court’s aggressive approach has led its approval ratings to plummet. In a recent Gallup poll, 58 percent of Americans said they disapproved of the job the Supreme Court was doing. Such findings seem to have prompted several justices to discuss whether the court’s legitimacy was in peril in recent public appearances.

Affirmative action. The marquee cases of the new term are challenges to the race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina. While the court has repeatedly upheld affirmative-action programs, a six-justice conservative supermajority may put more than 40 years of precedents at risk.

Voting rights. The role race may play in government decision-making also figures in a case that is a challenge under the Voting Rights Act to an Alabama electoral map that a lower court had said diluted the power of Black voters. The case is a major new test of the Voting Rights Act in a court that has gradually limited the law’s reach in other contexts.

Election laws. The court will hear arguments in a case that could radically reshape how federal elections are conducted by giving state legislatures independent power, not subject to review by state courts, to set election rules in conflict with state constitutions. In a rare plea, state chief justices urged the court to reject that approach.

Discrimination against gay couples. The justices will hear an appeal from a web designer who objects to providing services for same-sex marriages in a case that pits claims of religious freedom against laws banning discrimination based on sexual orientation. The court last considered the issue in 2018 in a similar dispute, but failed to yield a definitive ruling.

Justice Alito, who wrote the majority opinion in the decision in June overturning Roe v. Wade, raised a series of questions about the meaning and limits of originalism now that liberal justices have said they embraced it.

“Are we really all originalists?” he asked, mentioning one of the liberal members of the court. “Many people, including my colleague Elena Kagan, have said that ‘we are all originalists now.’ Is that true?”

Only to a point, he said. While many judges agree that the Constitution “should be interpreted in accordance with its original public meaning,” he said, “there is a lot of disagreement about how that meaning should be found.”

“To illustrate this, my Exhibit A is Obergefell v. Hodges,” he said, referring to the 2015 Supreme Court decision that said the due process clause of the 14th Amendment guaranteed the right to same-sex marriage.

Justice Alito dissented in that case, and in 2020 he joined a statement from Justice Clarence Thomas saying the Obergefell decision was at odds with the Constitution. In June, in his majority opinion in the abortion case, he said that ruling did not threaten other rights.

In his speech last month, Justice Alito focused on the “blistering dissent” in Obergefell written by “a pioneering originalist,” Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in 2016.

“To him and many other originalists, the decision in Obergefell was the precise opposite of originalism,” Justice Alito said. “In 1868, when the 14th Amendment was adopted, nobody — nobody — understood it to protect a right to same-sex marriage.”

He seemed to take Justice Kagan to task for her vote in that case. “Justice Kagan, who must regard herself as an originalist — she has said ‘we are all originalists now’ — joined the majority in Obergefell,” he said.

Justice Kagan discussed originalism at her own confirmation hearings, in 2010, saying that the framers of the Constitution had different goals in different parts of the document.

“Sometimes they laid down very specific rules,” she said. “Sometimes they laid down broad principles. Either way, we apply what they say, what they meant to do. So in that sense, we are all originalists.”

She elaborated on that statement last month in a public interview at Northwestern University that seemed to anticipate Justice Alito’s criticism.

A specific provision of the Constitution, like the one that says presidents must be at least 35 years old, needs no interpretation, she said.

In other provisions, she said, the framers “knew that they were writing for the ages” and so “wrote in broad terms and in what you might call vague terms.” Interpreting those provisions, she said, requires judgment and attention to contemporary reality.

“They had some understanding,” Justice Kagan said of the framers, “that life would change and that you were supposed to apply these principles — and you had to apply these principles — but to circumstances that they couldn’t imagine.”

In his speech, Justice Alito acknowledged that originalism has limits, particularly in cases that “could not have arisen at the time when the relevant constitutional provision was adopted,” mentioning a case concerning restrictions on the sale of violent video games.

When the case was argued in 2010, Justice Scalia asked what those who ratified the First Amendment thought about depictions of violence.

Justice Alito responded with a quip: “What Justice Scalia wants to know is what James Madison thought about video games. Did he enjoy them?”

Source: nytimes.com