He took part in studies that found the widening ideological divide to be the largest since post-Civil War Reconstruction.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

- Read in app

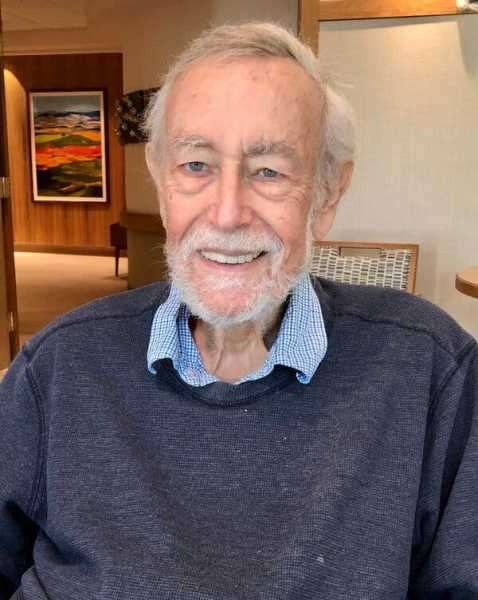

The political scientist Howard Rosenthal in an undated photo. He and several colleagues measured the widening ideological divide in Congress.

Prof. Howard Rosenthal, a political scientist whose pioneering research confirmed quantitatively that Congress is more politically polarized than at any point since Reconstruction, died on July 28 at his home in San Francisco. He was 83.

His son Prof. Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, a professor at the California Institute of Technology, said the cause was heart failure.

There was good news from the algorithm that Professor Rosenthal and his colleagues developed to analyze congressional roll-call votes: The ideological gap between the left and right had grown so great that, mathematically at least, it could not get much worse.

“Professor Rosenthal was a trailblazing figure in political science, who collaborated with economists and drew on game theory and other formal methods to help define the modern subfield of political economy,” said Prof. Alan Patten, chairman of the politics department at Princeton, where Professor Rosenthal taught between stints at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh and New York University.

“With his co-authors,” Professor Patten said, “he was especially known for work measuring and analyzing political polarization, a phenomenon that is of more relevance than ever in contemporary American politics.”

With his fellow professors Keith T. Poole of the University of Georgia and Nolan McCarty of Princeton, Professor Rosenthal systematically calculated the conservatism or liberalism of members of Congress.

In 2002, they concluded that a representative’s votes can generally be predicted on the basis of his or her previous positions on issues regarding race and on government intervention in the economy, like tax rates and benefits for the poor.

Their analysis showed that a legislator’s party affiliation was a much better augur of voting behavior than it had been 25 years earlier.

Moreover, they concluded, from 1955 to 2004 the proportion of unalloyed centrists in the House of Representatives had declined to 8 percent from 33 percent, and the number of centrist senators had dropped to nine from 39.

In 2013, with Professors Poole and McCarty and Prof. Adam Bonica of Stanford, Professor Rosenthal investigated why the nation’s political system had failed to come to grips with growing income inequality.

Among other conclusions, they found a correlation between the changes in the share of income going to the top 1 percent and the level of polarization between the political parties in the House.

The researchers also documented an increase in campaign contributions to Democratic candidates from millionaires listed in the Forbes 400 — as that list included more technology innovators than oil and manufacturing magnates — and a tack in the party’s platform from general social welfare policies to an agenda focused on identities of ethnicity, gender, race and sexual orientation.

In 2014, Professors Rosenthal and Poole and their collaborators wrote in The Washington Post that “Congress is now more polarized than at any time since the end of Reconstruction” in the 19th century

Samuel L. Popkin, a professor emeritus of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who befriended Professor Rosenthal when they were classmates there, said in an email that he was “the instigator or spark for most of the advances” in studying legislatures and voting. He credited Professor Rosenthal with developing new statistical measurements for analyzing data.

Howard Lewis Rosenthal was born on March 4, 1939, in Pittsburgh to Arnold Rosenthal, a businessman, and Elinor (Lewis) Rosenthal, a homemaker.

He received a Bachelor of Science degree in economics, politics and science in 1960 and a doctorate in political science in 1964, both from M.I.T. He was a professor at Carnegie Mellon from 1971 to 1993 and at Princeton from 1993 to 2005, and had been at N.Y.U. since 2005.

His marriage to Annie Lunel ended in divorce. His second wife, Margherita (Spanpinato) Rosenthal, died before him. In addition to his son Jean-Laurent, from his first marriage, he is survived by a daughter from that marriage, Illia Rosenthal; a son, Gil, from his second marriage; a sister, Susan Thorpe; and four granddaughters.

Predicting votes by members of Congress on the basis of statistical models built on previous votes was initially considered controversial. But one byproduct of those predictions, applied to election voters, went a long way toward establishing the model’s credibility.

“Challenged by a detractor to predict the 1994 midterm elections,” John B. Londregan, a political scientist at Princeton and a partner in one project, said in a statement, “we predicted a Republican majority in the U.S. House for the first time in almost 40 years, something that met with incredulity on the part of many colleagues.” They were, of course, right.

Professor Rosenthal was awarded the Duncan Black Prize from the Public Choice Society in 1980, the C.Q. Press Award from the American Political Science Association in 1985 and the William H. Riker Prize for Political Science from the University of Rochester in 2010.

In 1997, he and Professor Poole published “Congress: A Political-Economic History of Roll Call Voting.” With Professor McCarty, they wrote “Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches” (2006).

In 2007, after analyzing 2.8 million roll-call votes in the Senate and 11.5 million in the House, Professors Rosenthal and Poole produced an updated version of their 1997 book, which had predicted “a polarized unidimensional Congress with roll-call voting falling almost exclusively along liberal-conservative ideological lines.”

“We were right,” the authors concluded. “This makes us feel good as scientists, but lousy as citizens.”

Source: nytimes.com