They watched, waited and tried to help as the Afghan capital fell to the Taliban last year. “It was traumatic,” one said.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

- Read in app

Aug. 12, 2022Updated 6:42 p.m. ET

A veteran who desperately tried to connect Afghans with Marines at the airport in Kabul as the Taliban took over. A retired ambassador pulled in to lead the embassy. A young foreign service officer who lost her partner in an ambush.

A year after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, a group of Americans who served and worked in the country shared their frustrations, hopes and feelings of helplessness from a two-decade mission that still feels unfinished.

Credit…T.J. Kirkpatrick for The New York Times

“I think about it every day.”

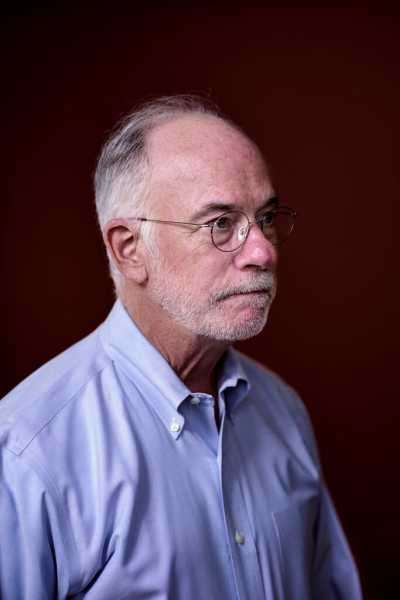

Ross L. Wilson

The Ambassador

On the morning of Aug. 15, 2021, Ross L. Wilson, the acting ambassador at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, received a dire security update from American military commanders. Gunfire was erupting around the Afghan capital as Taliban fighters closed in, and local security forces had abandoned their posts.

At the same time, the Taliban were expected to storm prisons in the area and release thousands of inmates, creating a potential surge of extremists and other criminals headed to Kabul.

It was the last of a steady drumbeat of warnings over the previous month as the Taliban gained strength across Afghanistan, and with it, Mr. Wilson resignedly ordered the embassy closed and the evacuation of about 1,500 Americans and other staff members. Documents were hurriedly burned and equipment destroyed.

“It was traumatic,” Mr. Wilson said, describing the events that led him and thousands of others to flee Afghanistan in late August. “People had to leave things behind — their possessions, their lives incredibly uprooted. And all of them are thinking about their Afghan friends, including colleagues or Afghan employees, but also people that they’d gotten to know and to care about.”

By midafternoon, a U.S. Marine had lowered the American flag from its pole outside the embassy and handed it to Mr. Wilson, who boarded a helicopter bound for the airport on the city’s edge. Left behind was not only the sprawling embassy compound but also a mission that was far from complete even after nearly 20 years of war.

“By that time, there was more than a gigantic question mark about our ability to come back any time in the very near future,” Mr. Wilson said. “It’s obviously a very sad day.”

It was about to get worse.

Most of the embassy’s staff left Afghanistan that night or early the next day. But Mr. Wilson and about 30 other American diplomats stayed on for two more weeks, trying to find and evacuate other U.S. citizens and permanent residents, and foreign allies, among the tens of thousands of panicked Afghans just outside the airport, begging to be rescued.

“They’re having to make choices: ‘Yes, you can come in,’ or ‘No sir, you can’t,’” Mr. Wilson recalled of the diplomats’ work at the airport gate during 12-hour shifts, amid gunfire and explosions, and against the constant roar of the crowd. “And you know, that’s really hard.”

“No one who wasn’t out there really can imagine how awful it was,” he said.

Mr. Wilson was among the four last diplomats to leave Kabul, departing on the final American military plane that flew out shortly before midnight on Aug. 30. The flight headed to Doha, Qatar, where he was taken to a military hospital for tests and was told he had the coronavirus. Few people wore masks during the long and devastating days at the Kabul airport, but Mr. Wilson had assumed the fatigue and other symptoms he had been experiencing were the result of working 20-hour days for five straight weeks.

He flew to his home outside Minneapolis to isolate and formally resigned his post at the end of September. That part had always been the plan: Mr. Wilson had retired from the Foreign Service in 2008 after a 30-year career as a diplomat. But he had never served in Afghanistan before he was asked, to his surprise, to fill in as the chargé d’affaires in January 2020 while the Trump administration and Congress fought over who to send as a permanent ambassador.

“To be honest, my reaction was, they should be asking other people who had served there,” Mr. Wilson said. But once asked, “it was my duty to do it.”

Nearly a year later, Mr. Wilson remains in touch with American diplomats who were with him during the final weeks in Kabul, many of whom he said were still shaken. The brutal memories have, in some cases, overshadowed the silver lining of an evacuation mission that spirited more than 124,000 people from Afghanistan.

He remains wary of the Taliban movement and cautions against recognizing its power as a legitimate government, even as he encourages the United States to continue working with, and helping, the Afghan people.

“There were lots of people left behind,” Mr. Wilson said. “And that’s on the burden side of the ledger for all of us.”

“It’s fair to say that everybody is carrying around a big set of burdens over decisions that were made, or that they were involved in; over actions they took and actions that weren’t taken, either individually or as a country,” he said.

“We all think about that. I think about it every day.”

— Lara Jakes

Credit…T.J. Kirkpatrick for The New York Times

“Use the Abbey Gate.”

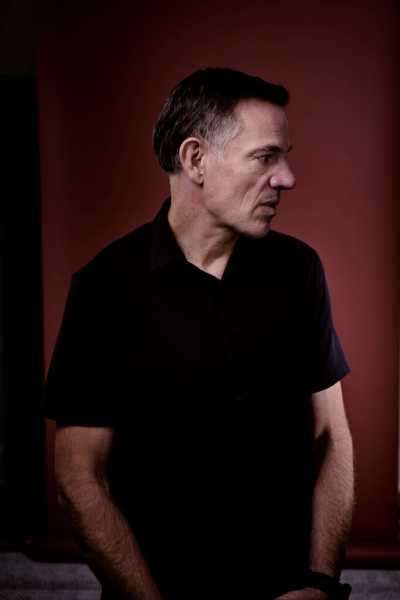

Jeff Phaneauf

10 Turbulent Days

Jeff Phaneuf was getting dressed for a wedding rehearsal dinner in northern Massachusetts when the call came that would change his life.

It was four days after the fall of Kabul, and on the line, from a gate at Hamid Karzai International Airport, was a fellow Marine. Mr. Phaneuf, who had left the Corps in early 2021, could hear chaos and gunfire in the background.

The situation at the airport was even worse than the news showed, his anguished friend told him. Marines were having to turn away thousands of Afghans who did not have paperwork. These were people who had helped American troops over the past 20 years, begging to be let in. There had to be a better system to get things moving.

So, Mr. Phaneuf set out to find one. One year later, he is still trying.

Mr. Phaneuf spent a turbulent 10 days desperately trying to connect Afghan allies with Marines at the airport’s Abbey Gate who could help them. He says he slept around 30 minutes a day, working the phones. He was on Twitter, issuing advice and telling people how to navigate Taliban guards: “Use the Abbey Gate,” read one tweet, at 3:32 p.m. on Aug. 23. “The canal entrance avoids TB checkpoints.”

When a suicide bomber attacked at the airport on Aug. 26, essentially shuttering all of the gates, Mr. Phaneuf shifted his attention to getting people out via other routes. By bus to Pakistan? Sure. By charter, sent from Qatar? OK.

He was attending Stanford University business school but was unable to focus on anything but his list of Afghan translators, fixers, drivers and families. “It’s pretty hard to focus on accounting when people’s lives are at stake and they’re asking you for help,” he said.

One night, Mr. Phaneuf was with friends at a party when he received a call about a breakthrough in one of his cases. “It was really surreal to be standing next to people playing beer pong, while I’m talking to someone who just boarded a plane and was waiting for it to take off.”

In March, he left Stanford. There would be time to go back to business school. A job had opened up, at No One Left Behind, a group that advocates for Afghans who helped Americans during the war.

On the day of this interview, Mr. Phaneuf was working on the case of the Afghan who was an interpreter for the Army’s 173rd Airborne Brigade, whose passport was burned by the American Embassy in Kabul when diplomats were rushing out. With no passport, the Marines at the gate could not help the man.

Fearing for his life, the interpreter fled to Pakistan, where, one year later, he was still waiting for an American Embassy to give him a visa.

— Helene Cooper

Credit…T.J. Kirkpatrick for The New York Times

“Terribly sad for the Afghan people.”

Kay McGowan

Loss, Pain and Hope

Kay McGowan still clearly remembers her first, thrilling months in Afghanistan.

Arriving at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul in 2003 as a young foreign service officer from Texas, she worked with a team charting the country’s post-Taliban future by devising a new Afghan Constitution.

“It was just an incredibly exciting, dynamic time,” Ms. McGowan recalled. She still remembers small things, like the absence of women’s bathrooms in Afghan government buildings. (The Taliban did not allow women to work outside their homes.) She took special pride in her efforts to ensure women would be represented in the new Afghan Parliament.

“We were at the center of creating a new nation-state. There was so much enthusiasm. Americans were so welcomed. The momentum was amazing.”

Ms. McGowan fell in love with the country — and with a man she met there: Steven MacQueen, a British citizen with a background in microfinance who worked for Afghanistan’s rural development ministry. By March 2005, she was expecting the birth of their daughter in a few weeks. On March 7 of that year, Mr. MacQueen was shot dead during an ambush in Kabul, less than a week before he planned to depart the country. Afghan authorities attributed his killing to a botched kidnapping attempt, but details were murky.

Ms. McGowan’s personal life was shattered, but she held out hope for Afghanistan. She continued to focus on the country, including as an adviser to the U.S. Agency for International Development. She watched the American withdrawal with “extreme frustration.”

“We really failed in our commitment to our Afghan partners,” Ms. McGowan said. “And all these women who bought into our vision for them are basically prisoners in their homes.”

She said it was particularly galling to hear senior U.S. officials suggest that Afghanistan’s security forces, who surrendered to the Taliban in large numbers in the spring and summer last year, had not fought hard. “I have never known people who lost more or fought longer,” she said.

After Kabul fell, Ms. McGowan worked frantically to assist Afghans who wanted to leave the country. “So many deserving people are still there,” she added.

A year later, Ms. McGowan feels some relief that, with the end of the war, Afghanistan has become a far less violent place. The air campaign during the Trump administration “was really brutal and devastating,” she said. “So I’m glad on one hand that at least the bloodletting for the most part has stopped. But I’m still terribly sad for the Afghan people — especially those who had worked hard and prepared for a different life.”

— Michael Crowley

Credit…T.J. Kirkpatrick for The New York Times

“I just cried with them.”

Lisa Maddox

Two Battlegrounds

Lisa Maddox came to the war late.

She had been serving as a diplomat for the State Department in New Delhi in 2012, working with the Indian government on security issues. The negotiations and conversations with her counterparts — a cerebral, stressful game of chess, she called it — often turned to Afghanistan.

When her India tour was over in 2014, Ms. Maddox returned to Langley, Va., to lead teams of analysts working on Afghanistan. Like many intelligence professionals, her career had touched on Afghanistan, but she believed that her experience in the region had given her a special perspective.

Drafting intelligence reports for the president and other senior leaders, Ms. Maddox would engage with the Afghanistan experts in the U.S. government.

“It was really intimidating to work the issue because what could you possibly offer when you had these longstanding experts that knew every angle to the story, knew the long, complicated history, with so many different nooks and crannies to it,” she said.

Ms. Maddox came in deciding to challenge old assumptions.

“A lot of people thought my questions were dumb, to be honest,” she said. “But sometimes my dumb questions sparked good discussions and new ideas.”

While there was a literal battleground in Afghanistan, there was a figurative one in Washington. The military and intelligence community had differing views of the American war effort. Intelligence analysts were pessimistic about the Afghan army and the Afghan government. The military saw progress.

“I saw more dissents in those finished intelligence reports on Afghanistan than any other subject I had worked on throughout my career,” Ms. Maddox said.

While in Washington, Ms. Maddox volunteered to go to Afghanistan, though the timing and length of her deployment remain classified.

As she studied the war, she was struck by the mission creep. The end goal for the United States, and how it intended to get there, was not clear. The fight had shifted from Al Qaeda to the Taliban. Well-intentioned projects had sucked up billions of dollars. The economy had been completely built around Western aid — and had become a corrupting force. The United States, she said, had “created a monster.”

“You kind of get cross-eyed at some point,” Ms. Maddox said. “And you ask, how does this end, where are we going with this? And when I studied the fight from an intimate perspective, I came to the conclusion this really looks unwinnable.”

When the collapse came, Ms. Maddox was not surprised, but she was overwhelmed by feelings of sadness and helplessness. By then, she had left government.

Ms. Maddox helped form a group to help Afghan families coming to America. She has continued to work with a pair of families, counseling them, listening to them, registering their children in school; assisting them with the basics of starting a new life.

“It was awful to hear what they had been through and the families they left behind,” Ms. Maddox said. “I talked to them and listened to their stories, honestly, I just cried with them.”

— Julian Barnes

Credit…T.J. Kirkpatrick for The New York Times

“Where are the women?”

Nicolette Waldman

A Return to Afghanistan

Upon returning to Afghanistan this spring after more than a decade away, Nicolette Waldman sensed a “very somber vibe” on the streets of Kabul, the capital.

“There was a real absence of women outside — and that was something that, I think, is increasing,” said Ms. Waldman, a human rights investigator for Amnesty International. “There was kind of a feeling of, ‘Where are the women?’ And that was very eerie.”

Ms. Waldman had last been in Afghanistan in 2012, when the nation’s women and girls were finding ways to go to school, work, influence politics and, generally, enshrine their rights in a society that had been largely closed to them during the Taliban rule of the 1990s.

Much of that progress has been reversed since the Taliban’s return to power last year. Women have been detained and beaten for attending protests, sent home from their jobs and forced out of shelters for victims of domestic violence, according to a report released by Amnesty International in late July.

It also concluded that women and girls increasingly were being arrested for appearing in public without a male relative, and that girls as young as 13 were being forced into arranged marriages.

Ms. Waldman was among the report’s researchers and helped interview some of the 90 women across the country about living anew under Taliban rule.

None of the people interviewed were identified in the report by their real names, a security precaution that Ms. Waldman said was allowed more liberally than Amnesty International usually permits. “This kind of sense of ‘everybody’s watching, everybody knows there’s nowhere to hide’ is real,” she said. “That, to me, seems like a real shift as well.”

As pervasive as the violence directed at Afghan women is the sense that the loss of liberties will reverberate for generations. In one case, Ms. Waldman noted, the Taliban fired a school principal whose salary had helped support her family. The other women at the school also were “dismissed and replaced by men,” Ms. Waldman noted. The setbacks, she said, were like “out of a dystopian novel.”

But Ms. Waldman also said the Taliban did not stop or try to censor her research, and she urged the international community to engage more with officials in Kabul to ensure that Afghan women continue to be heard.

She also sensed a resilience among Afghan women and girls “to push for that.”

“So many said, ‘We’re not the women of 20 years ago and we’re not going to stand for this,’” Ms. Waldman said. They conveyed “a sense of deep loss and depression,” she said, “but also so much momentum as well.”

— Lara Jakes

Credit…T.J. Kirkpatrick for The New York Times

“What was that all worth?”

Mercedes Elias

Waiting for News

At the veterans-run bank where Mercedes Elias works, the televisions are usually turned to business shows. But they were switched to cable news when the Pentagon accelerated its withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Ms. Elias, who had served in Afghanistan as a Marine captain, watched quietly with her colleagues as Afghan men and women streamed onto the tarmac at Kabul’s international airport, desperate to flee their country as the Taliban took over the city.

A year later, Ms. Elias is still bothered by what she saw.

“We all sat and kind of watched in horror at pictures of these people that are trying to throw their babies to Marines to give their kids a better life, people that are clinging on to a plane as it’s flying off the tarmac because they know the horror that is going to await them after the Americans leave,” she said. “All of us watched in dismay, and afterward we all internalized it in different ways based on where you’re at and how long you’ve been out, and what kinds of coping mechanisms you’ve developed since that time.”

On a companywide phone call later that day, Ms. Elias described what she and her colleagues had seen. She said that they were waiting for the roster of Marines killed that day to be released, hoping not to see the names of anyone they knew. She asked everyone to focus on what they could do, such as helping the families of the slain Marines.

Ms. Elias had served in Helmand Province, where she spent the first half of her deployment supplying a growing number of small outposts in the region — and the second half reversing course and directing the flow back to major logistics hubs like Camp Dwyer and Camp Leatherneck.

When she returned home in April 2012, it appeared to Ms. Elias that the war in Afghanistan was essentially over. That America’s full withdrawal 10 years later appeared so haphazard and unorganized seemed unconscionable to her, given that there had been so much time to plan.

“We were told that we were there to change the hearts and minds of the Afghani people, and especially important for me: that we were helping to liberate the women of Afghanistan and help get them better opportunities for education and freedom,” Ms. Elias said. “To see that, seemingly to us, nothing had changed, no progress had been made in 10 years, was just extremely frustrating and upsetting because you think about all the friends that you lost in-country or when you got back to suicide or addiction and things like that, it makes you think ‘What was that all worth?’”

Ms. Elias plans to discuss the anniversary of Kabul’s fall with her colleagues.

“You never really know where people are at in their coping and recovery process,” she said. “But the more you can talk about things that are upsetting like this, and that seem to have no path to resolution, maybe the more it will help more people kind of cope with it.”

— John Ismay

Credit…T.J. Kirkpatrick for The New York Times

“An overwhelming sense of loss.”

Laurel Miller

The Abandoned Embassy

Laurel Miller sometimes thinks about how the giant American Embassy compound in Kabul, built at a cost of around $800 million, now lies deserted.

Ms. Miller visited the embassy many times while serving as a representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan from 2013 to 2017, and today she is haunted by thoughts of the bleak symbol of America’s failed project.

“I think back to the time I spent on the compound, all the people who lived there, all the bureaucratic effort, not to mention financial commitments, that went into building up that embassy — sustaining it, securing it,” she said. “The endless hours of meetings about it. Some of the residential buildings there had only recently been completed. And then to picture it empty.”

Just as hard to fathom, said Ms. Miller, now director of the Asia program at the International Crisis Group, were the images of Taliban insurgents roaming through the Afghan presidential palace last August, in rooms where she had sat for meetings.

It is not that her experience in the country, which included about 20 visits over nearly two decades, had left her with any illusions. The fall of Kabul, she said, “was a reminder to me that it’s possible to be intellectually completely unsurprised and at the same time emotionally shocked. Because I wasn’t surprised by what happened.”

“By the time I joined the State Department we had already failed on the peacemaking front,” Ms. Miller said. “It was clear that American influence was ebbing, and was going to continue to ebb.”

Today she carries “an overwhelming sense of loss and futility. All those lives, all that effort, all that money — just to return to the status quo ante.”

Yet while the Taliban remain cruel and abusive, especially toward women, Ms. Miller said “there are things about how they’re governing that could be even worse.” The public executions that the Taliban carried out in the 1990s have not resumed, for instance. And she is mildly encouraged that “there is at least some engagement between the Taliban and the international community” that allows foreign governments to press for reforms.

It is also good news that the war’s death toll is over, she said.

But, she added, “it would be naïve to think the violent contest for power has ended for all time.”

— Michael Crowley

Credit…T.J. Kirkpatrick for The New York Times

“That was unexpected.”

Jeffrey Eggers

Questioning the U.S. Mission

In his new job, Cmdr. Jeffrey Eggers was to be the office contrarian, a devil’s advocate.

It was 2008, and Commander Eggers, a Navy SEAL, had started working for Adm. Michael G. Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In his new role, Commander Eggers was expected to raise sharp, fundamental questions about the U.S. approach to Afghanistan just as the United States was considering a far more expansive counterinsurgency plan.

He had fought in Iraq with the SEALs and served on President George W. Bush’s national security staff, work that left him uncertain about whether a counterinsurgency in Afghanistan “was biting off too much.”

Commander Eggers went on to be a key adviser to Admiral Mullen’s pick to be the commander of international forces in Afghanistan, Gen. Stanley McChrystal. Working in Afghanistan, Commander Eggers continued to grapple with questions about America’s approach to the war. His experience reinforced his belief that the U.S. mission should be better defined and more constrained.

War in Afghanistan might have been inevitable after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, but making the Taliban the enemy was not. The group that perpetrated the attacks was, of course, Al Qaeda, and Commander Eggers believed a “right-sized” response would have been a campaign focused only on terrorism.

Getting the enemy wrong in Afghanistan meant that the U.S. strategy was inevitably flawed, overextending the U.S. military and depleting American resources, which might have been Al Qaeda’s goal from the start.

“We found ourselves inadvertently, or perhaps inevitably, in a counterinsurgency campaign, when we should have been in a counterterrorist campaign,” Mr. Eggers said.

Such debates continued through the Afghanistan war — right until the end. In the Obama administration, Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. pushed for a more limited mission, views that influenced his decision as president to end the war and withdraw American forces last year.

When that decision resulted in a Taliban takeover, it was a difficult moment for many veterans.

“For those that were close to the war, and the trajectory of the war, you knew that it was never going to end fully on America’s or NATO’s terms,” Mr. Eggers said. “It wouldn’t have been surprising for the Taliban to end up as a part of the government. But for the Taliban to become the entire government? That was unexpected.”

Mr. Eggers argues that the American public was too little involved in the debate over the war, in part because there was no draft, and in part because technologies like the armored vehicles known as MRAPs appeared to keep casualty rates low, at least later in the war. But many veterans returned home with traumatic brain injuries and other hidden wounds.

Today, Mr. Eggers helps run the Risk and Return Foundation as well as a venture capital fund that invests in projects that bring new capabilities to the military and services to support veterans living with the wounds of war.

“The overall impact and real level of casualties is much larger than what we could see,” Mr. Eggers said. “Because of the nature of war and technology, much of that was hidden from sight. We’re just now starting to understand the true magnitude of what the real casualties of this era of warfare look like.”

— Julian Barnes

Source: nytimes.com