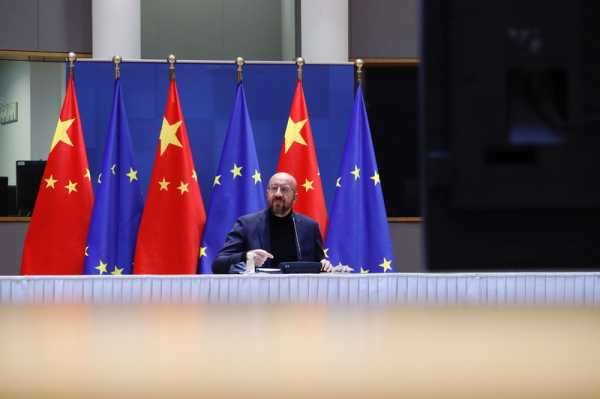

Beijing's tacit endorsement of Russia's unprovoked aggression, has changed the calculation in Brussels (Photo: consilium.europa.eu)

The West’s pivot to the Indo-Pacific, aimed at countering expanding Chinese influence, has won consensus among decision-makers in Washington, Paris and London over recent years. But Vladimir Putin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine has triggered a reassessment of the policy. A more nuanced picture is now emerging.

According to a recent Bloomberg report, the Biden administration’s National Security Strategy, due to have been published in January, is being rewritten to reflect a growing recognition of the intertwined nature of the challenges posed by Russia and China.

-

In comparison to his combustible predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte (picture), Philippines president-elect Bongbong Marcos is someone Europe can do business (Photo: Wikimedia)

The Kremlin’s isolation, and Beijing’s tacit endorsement of its unprovoked aggression, has changed the calculation.

In Europe, the recalibration of priorities towards a more integrated Eurasian strategy of containing both Russia and China will be welcomed — not least by countries on Nato’s eastern flank. But it should also prompt reflection among EU policymakers about the continent’s approach to countering Chinese influence as a strategic competitor.

The growing alignment between China and Russia means that Beijing’s rising influence in the Indo-Pacific has a direct impact on the many security challenges in Europe emanating from Moscow.

A Russia more dependent on Chinese support will find its ability to wreak havoc in Europe increasingly dictated by whether China is emboldened in its own backyard.

Even as war flames in Ukraine, therefore, Europe cannot neglect to compete with China for global influence. No longer can it be considered a concern primarily for the US and Western partners in the Indo-Pacific region. The question then becomes a simple one: how can the EU support the West’s wider containment strategy, especially in the Indo-Pacific?

As much as military muscle, the answer lies in trade. The EU is the most powerful trade bloc in the world, with economic might its most significant strategic asset. Its ability to impose crippling sanctions against the Russian economy has demonstrated the geopolitical weight that brings.

In the Indo-Pacific, Brussels must place its economic strength at the heart of its efforts to build influence in the region. A renewed policy of trade diplomacy with ASEAN nations is required.

In truth, the continent has been comparatively slow off the mark in responding to China’s aggressive economic and diplomatic outreach to ASEAN nations with economic advocacy of its own.

The Biden administration’s recent launch of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), while limited in substance, is a useful blueprint for proactive engagement with some of the fastest growing economies in the world.

Ambition in strengthening relationships will be key. Despite facing significant hurdles due to the differing stages of development among south-east Asian economies, an EU-ASEAN trade deal must be the goal.

Europe should look to establish long-term economic partnerships which go beyond trade in commodities and goods, and advance cooperation in technology, skills sharing and the promotion of environmental and safety standards.

There are already strong foundations to work with. Over the course of four decades both the EU and ASEAN nations have benefited from deepening trade and economic relations.

Indonesia — ‘sleeping giant’

Bilateral trade deals with Singapore and Vietnam are already in place. A renewed effort must now take place to push forward partnership agreements with ASEANs two largest countries by population: Indonesia and the Philippines.

As the largest Muslim economy in the world and the largest of the ASEAN economies, Indonesia is the sleeping giant of the region. A fact that was long overlooked and underestimated by Europe, by the West as a whole. Predicted to become the fourth largest economy globally by 2050, it can be the centrepiece of any strategy to balance China’s influence in the region. After the loss of Russia and Ukraine as suppliers of energy and raw materials, Indonesia will play an important role as an exporter of gas and raw materials in particular for Europe and the West.

This is one reason why carmaker Tesla wants to build its third gigafactory in Indonesia due to its high nickel and tin deposits.

The building blocks for cooperation are in place.

In November last year, the EFTA states signed a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement with Indonesia and the EU is already Indonesia’s fifth-largest trading partner.

‘Combustible predecessor’ in Philippines

The Philippines, meanwhile, is already a strategically important partner for Western engagement in the region and holds a mutual defence pact with the United States. The island nation has faced Chinese territorial encroachment in the South China Sea since a 2016 ruling found in favour of the Philippines’ territorial rights in the West Philippines Sea.

The recent election of Bongbong Marcos as the country’s next president represents a key opportunity for European engagement. A Western-educated leader, he has already signalled to European representatives his eagerness to deepen cooperation and a pragmatic openness to areas of mutual cooperation.

In comparison to his combustible predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte, president-elect Marcos is someone Europe can do business with and can certainly put him on the path to improving the human rights or corruption situation and understanding sustainability as a business model for his country.

In the era of strategic competition, deal-making and an ambitious approach to partnerships with ASEAN economies is precisely what is needed.

In turn, bilateral engagement with SE Asia’s giants in Indonesia and the Philippines will strengthen the case for the holy grail of its Indo-Pacific trade diplomacy: an EU-ASEAN trade deal which could and should lead one day in a free trade agreement to boost growth and strength on both sides.

To get there, work must start now. Europe’s core security interests increasingly depend on it.

Source: euobserver.com