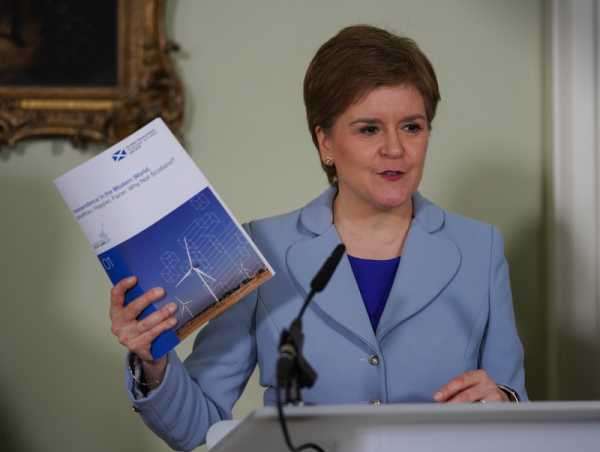

Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon, launching the independence poll plan last week in Edinburgh (Photo: Scottish Government/Flickr)

When Nicola Sturgeon, first minister of Scotland, launched her government’s new campaign for Scottish independence in Edinburgh last week, she sought to re-energise Scotland’s defining debate.

The question of whether Scotland should remain part of the United Kingdom or become a separate state is the cornerstone, however imperfect, repetitive, and consuming, of modern Scottish politics.

That debate never diminished after Scotland’s 2014 independence referendum. Major events — Brexit, the pandemic and now the Ukraine war, among others — become integrated into the constitutional debate. They change the context, but are mainly used to express the same arguments in new ways.

Yet, for the Scottish government and the leadership of Sturgeon’s ruling Scottish National Party (SNP), the subject of independence had been in a form of abeyance since the onset of the pandemic.

No longer. In her launch speech, Sturgeon declared plainly that “it is time to talk about independence.”

It is an unspoken truth that the SNP is somewhat overfond of freshly-minted government publications as ready props. True-to-form, the independence campaign launch featured a new Scottish government report, comparing the UK’s economic and social record with those of other European states — and arguing, unsurprisingly, that Scotland should be independent as a result.

This report is the first of what will be a series addressing core aspects of the independence debate, including currency, trade and EU membership. Together, they are intended to constitute the Scottish government’s new prospectus for realising independence in the post-Brexit world.

Since 2017, and mostly due to Brexit, the Scottish government has argued that a new independence referendum should take place. After last May’s Scottish parliamentary election, the SNP pledged to hold a referendum by the end of 2023. It was suggested last week that it has October 2023 in mind.

Listening to the SNP and the Scottish Green Party, which supports the former in government, the impression is that a new referendum is an immutable certainty and independence a close prospect.

London says ‘no’

In reality, that is only half of the picture. The UK government has opposed the premise of a second referendum for as long as the Scottish government has advocated it. Their dispute seems intractable, and a unilateral campaign launch is not going to generate a resolution.

This referendum impasse raises foundational questions: on the nature of power within the British state, the suitability of an amorphous constitution and the locus of democratic authority for Scotland.

However, regardless of those, the practicalities remain the same. For Scotland to have a viable pathway to independence, both the Scottish and UK governments would have to cooperate closely at every stage. To become a new state, Scotland would need the support of its old one.

That is the fact which some in the Scottish independence movement want most to ignore. Incredulity is the response to any suggestion that Scotland’s future statehood would be subject to the realities of international relations — and the necessity for the UK state to endorse Scottish independence as well.

In 2014, London backed the referendum and both sides agreed to implement its result. Today, that kind of consensus is non-existent. In its absence, the Scottish government has decided to stare down the UK government and, by means unknown, force it to accept a vote.

This referendum strategy is a massive gamble on the part of the SNP.

At the campaign launch, Sturgeon signalled that the Scottish government was prepared to hold a unilateral referendum. She did not set out a plan for reaching agreement with the UK government. Instead of seeking to build bridges with UK prime minister Boris Johnson — the one person whose support is most needed for a referendum — Sturgeon lampooned his democracy credentials.

For now, it is totally unclear how the Scottish government expects to translate its adversarial posture into an endorsement of a referendum by the UK government. The SNP and the Greens could surely help themselves by approaching Johnson more like the foreign leader that they want him to become via independence — with tact, not insults.

The SNP’s leadership feels the impatience within its membership and the wider independence movement for a referendum. If the party entered the next Scottish parliament election in 2026 without having held a referendum, the reception from traditional supporters could be perilously frosty.

The Scottish public remains fairly evenly split on the question of independence, according to polls, with the pro-UK side slightly ahead. If a vote did happen, neither side would start with a commanding lead.

The chances of a bone fide Scottish independence referendum taking place in 2023 remain uncertain. The Scottish government may well refine its approach in the months ahead.

For the moment, however, it is on a collision course with the UK government. It would be in the best interests of all concerned to find an alternative route.

Source: euobserver.com