A Times reporter who covers Guantánamo Bay tracked down military photographs of the early days of the U.S. detention center there.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

- Read in app

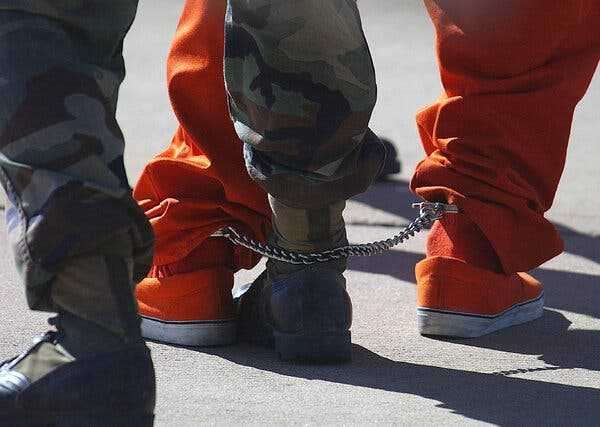

One of the first detainees was processed at the Guantánamo Bay detention on Jan. 11, 2002.

Times Insider explains who we are and what we do and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.

GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba — Like so many articles, our project in Sunday’s newspaper on the once-secret Pentagon photos from the earliest days of U.S. detention operations here, in 2002, started out with a tip.

Somewhere inside the Pentagon was a trove of pictures taken by photographers from the elite Combat Camera unit, someone who had worked at the prison told me last year. The military photographers spent months documenting the goings-on at Guantánamo Bay in the first year after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

The pictures had been taken for senior leaders at the Pentagon — especially for Donald H. Rumsfeld, the defense secretary who took a personal day-to-day interest in the detention center. And they were definitely not meant for the public to see.

I thought back to the day the first prisoners arrived from Afghanistan at this remote base, on Jan. 11, 2002. I was among a group of journalists who were allowed to watch from a rise above the airstrip as the prisoners were led off a steel gray cargo plane — manacled, masked and in matching orange uniforms. Nearby, my colleague from The Miami Herald, the photographer Tim Chapman, paced around our vantage spot in frustration — he had not been allowed to bring his cameras to document the moment. To his dismay, he spotted military photographers down on the airstrip, the place he wanted to be.

The world would glimpse the work of one of those photographers, Petty Officer Shane T. McCoy of the Navy, about a week later, when the military released five of his pictures, including one that came to symbolize Guantánamo Bay: 20 men on their knees inside a chain-linked enclosure on opening day.

And nearly 20 years later, I was learning that many more photos from that time had been sent from Guantánamo to the Pentagon. On a winter day in Washington, the hunt for those images began.

One office in the Department of Defense sent me to another.

Some people pointed me to the Library of Congress. Others were certain some photos had landed at the National Archives, and that turned out to be true.

I submitted a series of requests under the Freedom of Information Act, followed up with calls and emails and in time learned of various collections with Guantánamo material, much of it classified.

Then one day earlier this year, an archivist sent word that some material had already been declassified. A zip file arrived in my email and photos of men in orange uniforms splashed onto my computer screen.

Some of what I saw in those images of the first year, which are published in The Times, I understood because I had been reporting at the base then. But other things puzzled me and required digging.

I explained what I had to Marisa Schwartz Taylor, a photography editor for The Times in Washington. We looked at the photos together and agreed that this was something special — the kind of FOIA return that does not end a reporting task, but rather begins one. She made an initial edit, asked many questions and set me on my path. She enlisted Rebecca Lieberman, a digital news designer for The Times, and the teamwork began.

With the three of us in different locations — Rebecca in New York, Marisa in Washington and me mostly in Miami Beach or at Guantánamo — we pored over the images and decided that we needed more information to put them into context. Rebecca drew up a design that would annotate the photos, offering a guide to readers of what they were seeing.

I reached out to retired military members who had worked at the prison from the start. Many people I wrote or called were intrigued. A few snubbed me; they would not talk about the early days of a military mission that for some had soured across the years.

The Dallas-based photographer Jeremy Lock, now retired from the Air Force after a celebrated career with Combat Camera, was excited when I contacted him. He wondered when the world would ever get to see his work from that day.

Carol Rosenberg has reported from the U.S. naval base and military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, since 2002. She joined The New York Times in 2019.

Source: nytimes.com