The Texas senator challenged a federal law that put a $250,000 cap on repayments of candidates’ loans to their campaigns using postelection contributions.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this articleGive articleGive this storyGift this article

- Read in app

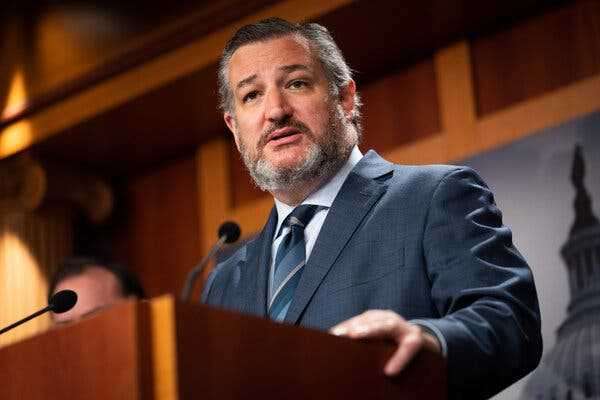

Senator Ted Cruz, Republican of Texas, argued that the repayment cap violated the First Amendment.

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court on Monday ruled in favor of Senator Ted Cruz in his challenge to a federal law that limits how political campaigns can repay candidates for money they lend their own campaigns. The ruling was the latest in a series of decisions dismantling various aspects of campaign finance regulations on First Amendment grounds.

The court split along the usual lines, 6 to 3, in deciding that Mr. Cruz, Republican of Texas, was entitled to be reimbursed using postelection donations for money he had lent his campaign in 2018. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., writing for the majority, said the challenged law “burdens core political speech without proper justification,” violating the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court has said that only corruption or its appearance can justify campaign finance limits. “We greet the assertion of an anticorruption interest here with a measure of skepticism,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote.

In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that the law was squarely aimed at preventing corruption.

“Repaying a candidate’s loan after he has won election,” she wrote, “cannot serve the usual purposes of a contribution: The money comes too late to aid in any of his campaign activities. All the money does is enrich the candidate personally at a time when he can return the favor — by a vote, a contract, an appointment. It takes no political genius to see the heightened risk of corruption.”

The basic dispute was whether contributions to winning candidates to repay personal loans to their campaigns were a form of political speech or a kind of gift with the potential to corrupt.

The challenged law placed a $250,000 cap on the repayment of personal loans from candidates to campaigns using money from postelection donations. Seeking to test the constitutionality of the law, Mr. Cruz lent $260,000 to his 2018 re-election campaign.

A related regulation allows repayment of loans of more than $250,000 so long as campaigns use pre-election donations and repay the money within 20 days of the election. But the campaign did not repay Mr. Cruz by that deadline, so he stood to lose $10,000.

Chief Justice Roberts, noting that the 2018 Senate race in Texas was at the time the most expensive in history, wrote that it was undisputed under the court’s precedents that candidates can spend their own money without limitation on their own campaigns.

The challenged law, he wrote, “inhibits candidates from loaning money to their campaigns in the first place, burdening core speech.”

The chief justice wrote that loans played a special role for candidates challenging incumbents.

“As a practical matter, personal loans will sometimes be the only way for an unknown challenger with limited connections to front-load campaign spending,” he wrote. “And early spending — and thus early expression — is critical to a newcomer’s success. A large personal loan also may be a useful tool to signal that the political outsider is confident enough in his campaign to have skin in the game, attracting the attention of donors and voters alike.”

Chief Justice Roberts added that the usual $2,900 cap on contributions continued to apply under the law, meaning that 86 donations are permitted before reaching the $250,000 limit, undercutting the argument that the law combats corruption.

He said there was no evidence that the law gave rise to corruption, as candidates whose loans are repaid are merely being made whole. “If the candidate did not have the money to buy a car before he made a loan to his campaign,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote, “repayment of the loan would not change that in any way.”

That argument, Justice Kagan wrote in dissent, “altogether misses the point.”

“However much money the candidate had before he makes a loan to his campaign,” she wrote, “he has less after it: The amount of the loan is the size of the hole in his bank account. So whatever he could buy with, say, $250,000 — surely a car, but that’s beside the point — he cannot buy any longer. Until, that is, donors pay him back.”

Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel A. Alito Jr., Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett joined the majority opinion, and Justice Stephen G. Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor joined the dissent.

The case, Federal Election Commission v. Ted Cruz for Senate, No. 21-12, arose from a lawsuit that Mr. Cruz filed against the commission before a special three-judge district court in Washington, arguing that the repayment cap violated the First Amendment.

Judge Neomi Rao, who ordinarily sits on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, wrote for a unanimous panel that the cap amounted to an unconstitutional burden on candidates’ free speech rights.

“Protections for political speech extend to campaign financing because effective speech requires spending money,” Judge Rao wrote, adding that “the loan-repayment limit intrudes on fundamental rights of speech and association without serving a substantial government interest.”

Defending the law in the Supreme Court, the Biden administration noted that Mr. Cruz’s campaign had more than $2 million on hand after the election and could have lawfully repaid him from those funds so long as it did so within 20 days. His injury, lawyers for the administration said, was self-inflicted.

Chief Justice Roberts rejected that argument, saying that Mr. Cruz was entitled to challenge the constitutionality of the law.

When the case was argued in January, Charles J. Cooper, a lawyer for Mr. Cruz and his campaign, said contributors should be able to “exercise the First Amendment right to associate with the winner, and to hope that that will result in the kind of influence and access that support for a candidate begets.”

Source: nytimes.com