To explain its puzzling rejection of dozens of textbooks, the state released 6,000 pages of comments, revealing an often confusing and divisive process.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

- Read in app

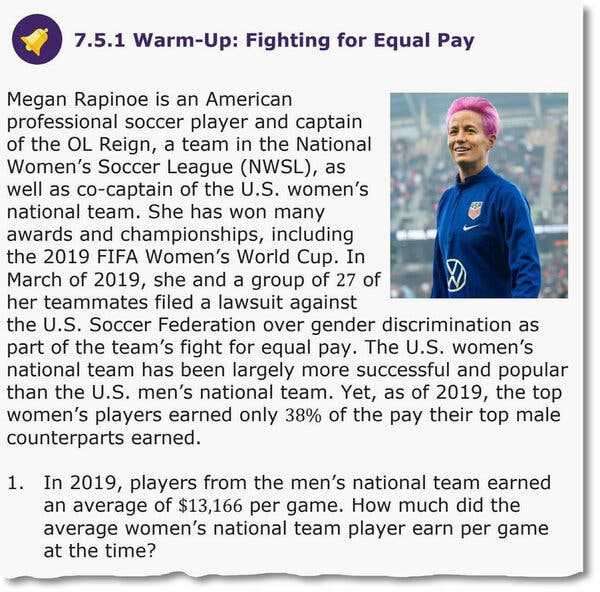

A reviewer flagged this word problem about pay equity that included Megan Rapinoe.

By Dana Goldstein and Stephanie Saul

May 7, 2022, 10:54 a.m. ET

It was the equivalent of: “Show your work.” To help explain its puzzling rejection of dozens of math textbooks, the state of Florida released nearly 6,000 pages of reviewer comments this week and revealed an often confusing, contradictory and divisive process.

A conservative activist turned textbook reviewer was on the lookout for mentions of race. Another reviewer didn’t seem to know that social-emotional learning concepts, like developing grit, should be banned, according to the state. A third flagged a word problem comparing salaries for male and female soccer players.

As part of the official review process, the state assigned educators, parents and other residents to review textbooks, in part to determine whether they adhered to Florida’s teaching standards for math — from simple addition in kindergarten to interpretation of graphs in high school statistics.

But Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, and allies in the state legislature have also fought against what he calls “woke indoctrination” in public schools and advanced a series of regulations and laws intended to limit how race, gender and social-emotional subjects are taught.

So reviewers were asked to flag “critical race theory,” “culturally responsive teaching,” “social justice as it relates to CRT” and “social-emotional learning,” according to the documents.

In an illustration of how politicized and subjective those terms have become, the various reviewers seldom agreed on whether those concepts were present — and, if they were, whether the books should be accepted or rejected for including them.

While many states and school districts appoint textbook reviewers, Florida’s process has been highly unusual. Some reviewers considered race and social-emotional learning alongside detailed points of math content and pedagogy, while others looked only for critical race theory, according to the documents.

It is not clear why particular reviewers took on a more narrow task, and the Florida Department of Education did not immediately respond to a list of written questions about the review process.

But in an April news release announcing the textbook rejections, the department said, “Florida’s transparent instructional materials review process ensures the public has the opportunity to review and comment on submitted textbooks.”

And Governor DeSantis has said that he thinks concepts like social-emotional learning are a distraction from math itself.

ImageGov. Ron DeSantis has advanced a series of regulations and laws intended to limit how race, gender and social-emotional subjects are taught.Credit…Alan Youngblood/Ocala Star-Banner, via Associated Press

“Math is about getting the right answer,” he said at a news conference last month, adding, “It’s not about how you feel about the problem.”

Conservative activists were involved in the review process. For example, five reviewers read “Thinking Mathematically” from the publisher Savvas Learning Company, a rejected high school textbook. Only one of the reviewers — Chris Allen, a parent in Indian River County and an activist with the conservative group Moms for Liberty — flagged the book for including critical race theory and social-emotional learning.

In detailed comments, Ms. Allen, 33, objected to math problems that, she wrote, suggested a correlation between racial prejudice, age and education level and that called attention to the wage gap between women and men.

She also cited several topics for being “not age appropriate,” such as mentions of divorce and drug and alcohol use.

In an interview, Ms. Allen, who works in engineering, said she first heard about the opportunity to review textbooks in January, through a local activist email list known as the Education Action Alliance. At the time, Florida had put out a call for volunteer “guest reviewers.”

She described herself as “a newcomer” to state politics who first got involved during the pandemic, to resist school mask mandates. She has also been active in efforts to remove what she referred to as “pornographic books” from school libraries.

Understand the Debate Over Critical Race Theory

Card 1 of 5

An expansive academic framework. Critical race theory, or C.R.T, argues that historical patterns of racism are ingrained in law and other modern institutions. The theory says that racism is a systemic problem, not only a matter of individual bigotry.

C.R.T. is not new. Derrick Bell, a pioneering legal scholar who died in 2011, spent decades exploring what it would mean to understand racism as a permanent feature of American life. He is often called the godfather of critical race theory, but the term was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1980s.

The theory has gained new prominence. After the protests born from the police killing of George Floyd, critical race theory resurfaced as part of a backlash among conservatives — including former President Trump — who began to use the term as a political weapon.

The current debate. Critics of C.R.T. argue that it accuses all white Americans of being racist and is being used to divide the country. But critical race theorists say they are mainly concerned with understanding the racial disparities that have persisted in institutions and systems.

A hot-button issue in schools. The debate has turned school boards into battlegrounds as some Republicans say the theory is invading classrooms. Education leaders, including the National School Boards Association, say that C.R.T. is not being taught in K-12 schools.

The Florida Department of Education, she said, had been more responsive to her concerns than her local school board.

“These are for high school children,” she said. “You are still finding out who you are and figuring out your place in the world. This math book tells you, depending on your age, you might be racially prejudiced.”

From the documents, it seems that some reviewers did not understand that they should reject textbooks with social-emotional learning, a mainstream education movement intended to help students develop skills like cooperation and grit. It is widely taught in colleges of education and professional development sessions.

A first-grade book, published by Savvas, for instance, includes concepts such as striving to “disagree respectfully” about how to solve a math problem, and prompts students to “use a growth mind-set” when stuck.

One reviewer, apparently a teacher, noted that the book “provides good strategies for SEL.” But then, the same reviewer also said the book did not have content related to social-emotional learning. The textbook was rejected anyway.

Study Edge’s 7th grade “Accelerated Math” textbook was rejected after one of the reviewers who recommended it raised questions about a “warm up” activity that “includes a controversial topic regarding equal pay and discrimination.”

A look at the textbook suggests that the reviewer, an algebra teacher in Orlando, was referring to a word problem comparing salaries for male and female soccer players using Megan Rapinoe as an example.

Many of the textbooks were rejected by the state despite strong reviews from math teachers, who complimented the books for being engaging and thorough and having rich digital resources. Some teacher reviewers gave detailed feedback on how the various texts would help or hinder students in math, often referencing their own classroom experiences.

But in the end, for dozens of books, those comments were less important than those flagging issues of race, gender and social-emotional learning.

Over the past several weeks, some publishers agreed to revise their rejected books. Florida law also allows the companies to appeal the rejections.

Source: nytimes.com