The justices will decide whether the artist’s reliance on a photograph of the musician was copyright infringement or protected as a new, transformative work.

-

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have “>10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

- Read in app

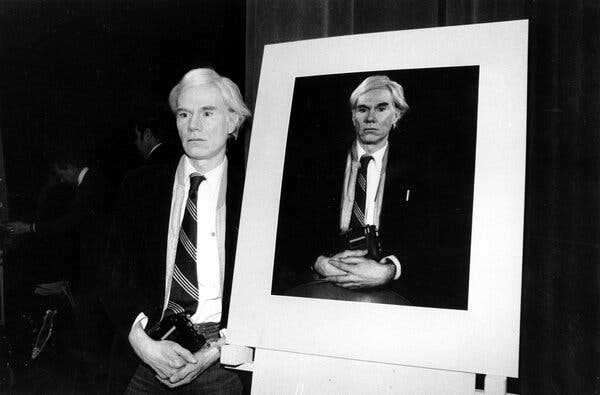

Andy Warhol standing next to a self-portrait in 1978. Much of the litigation that followed in the case before the Supreme Court focused on whether Warhol had transformed a photograph of the musician Prince.

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court agreed on Monday to decide whether Andy Warhol violated the copyright law by drawing on a photograph for a series of images of the musician Prince.

The case will test the scope of the fair use defense to copyright infringement and how to assess if a new work based on an older one meaningfully transformed it.

The black-and-white image that Warhol used was taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith, a prominent photographer whose work has appeared on more than 100 album covers.

Ms. Goldsmith licensed the image to Vanity Fair in connection with a 1984 article, and Warhol altered it in a variety of ways, notably by cropping and coloring it to create what his foundation’s lawyers described as “a flat, impersonal, disembodied, masklike appearance.”

The image accompanied an article titled “Purple Fame” and appeared around the time of Prince’s album “Purple Rain.”

The Enduring Legacy of Andy Warhol

The artist’s cultural prominence has hardly diminished in the decades since his death in 1987.

- Warhol-mania: If Andy Warhol seems particularly ubiquitous right now, that’s because he is: onscreen, in museums and in the streets.

- A Play: In “The Collaboration,” Paul Bettany and Jeremy Pope give memorable performances as Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

- A Book: “Warhol” by Blake Gopnik, the first true biography of the artist, reveals a narrative that gets more complex the more closely you look.

- A Musical: “Andy,” Gus Van Sant’s Warhol-inspired stage debut, may be the movie director’s oddest tribute to date.

- An Exhibition: “Andy Warhol: Revelation” at the Brooklyn Museum shows how Catholicism seeped into the Pop master’s work.

Before Warhol died in 1987, he created 15 other images of Prince drawing on the same photograph. When Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair published a special issue celebrating his life and used one of those images, alerting Ms. Goldsmith to the existence of the other works.

Litigation followed, much of it focused on whether Warhol had transformed Ms. Goldsmith’s photograph, a question that figures in the fair-use analysis. The Supreme Court has said that a work is transformative if it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.”

In 2019, Judge John G. Koeltl of the Federal District Court in Manhattan, ruled for the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, which holds Warhol’s own copyrights in the images, saying that the artist had transformed the musician depicted in Ms. Goldsmith’s photograph “from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

“The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone,” Judge Koeltl wrote. “Moreover, each Prince series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince — in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.”

A unanimous three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in New York, reversed Judge Koeltl’s ruling.

“The district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue,” Judge Gerard E. Lynch wrote for the panel. “That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.”

The judge’s task, Judge Lynch wrote, is to assess whether the later work “remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material.” Warhol’s Prince series, Judge Lynch wrote, “retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements.”

It was irrelevant that the new images were instantly recognizable as Warhols, Judge Lynch wrote.

“Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others,” he wrote.

Lawyers for the Warhol Foundation told the Supreme Court that his Prince series transformed Ms. Goldsmith’s photographs by “commenting on celebrity and consumerism.”

The Second Circuit’s approach, they wrote, “will chill artistic expression and undermine First Amendment values,” “threatens a sea change in the law of copyright” and “casts a cloud of legal uncertainty over an entire genre of visual art.”

Lawyers for Ms. Goldsmith wrote that “Warhol’s silk-screens shared the same purpose as Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph and retained essential artistic elements of Goldsmith’s photograph.”

The Second Circuit’s decision was routine and limited, they wrote in urging the justices to turn down the foundation’s petition seeking review in the case, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith, No. 21-869. The foundation’s lawyers, they wrote, “take a Chicken-Little approach to the decision below, but the sky is not remotely close to falling.”

Source: nytimes.com