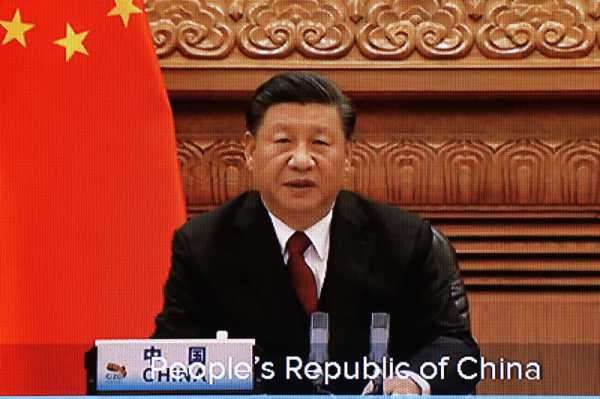

One assessment should be clear for Europe: the larger strategic challenge for Europe still lies in a rising China (Photo: consilium.europa.eu)

On the opening day of the 2022 Winter Olympics, China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin declared a “friendship between the two states with no limits, no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation,” promising to stand alongside each other on conflicts over Ukraine and Taiwan and to collaborate more against the West.

Has the West’s nightmare of a Sino–Russian relationship evolving into an “authoritarian alliance,” acting as an alternative centre of gravity to Western liberal democracies now become true?

In contrast to this propagandistic closing of ranks, the Russian War on Ukraine has brought China into a rather delicate position.

The most recent decision of the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB), largely dominated by China, to freeze lending to Russia and Belarus over the Ukraine war and the country’s behaviour in the UN Security Council stem from this dilemma.

The Russian aggression will also calls into question the gains of the ever-closer cooperation between China and Russia in many fields.

Russia’s dependency on Western markets remains strong despite a massive increase in Sino-Russian trade exchanges over the last ten years. The country is far from able to completely substitute its economic relationship with the West for logistical, technological, and financial reasons.

What came as a major surprise not only to Moscow, but also to Beijing, was the unprecedented reaction of Western nations and their allies in Asia to the Russian aggression, by its speed, scope, and effectiveness.

This counterstrike stood in sharp contrast to what Russian elites have long believed in: the narrative of a weak, declining West, an idea which had also gained a lot of followers among Chinese politicians and large parts of their population.

The war on Ukraine will be recognised as a watershed moment in defence strategy, and not only among Western democracies, given that the security architecture of the entire Eurasian continent and its periphery is at stake.

Whatever the fate of Ukraine, there will be detrimental consequences for Russia but also for China. For Russia, the structural imbalances of its relationship with China are manifold: a resource-based export model, a declining and ageing population, and weaknesses in its internal governance.

Because of the harsh sanctions regime, Russia’s asymmetric position within the partnership — at least in economic and technological terms — will only deteriorate further, giving China an upper hand in bilateral terms of trade, i.e. in energy imports, leading to additional comparative advantages for the Chinese economy.

This casts additional doubt as to whether China will join in any “modernisation partnership”, which the EU had offered Russia in 2010.

It will be interesting to closely follow the lessons China will draw out of this conflict. What can already be said is that the country will speed up its efforts to further decouple its economy and strengthen its resilience against any form of economic warfare.

New global arms race

But even China will not necessarily be laughing. The shockwaves of economic recession will affect China’s economy, as consumption patterns and investment strategies in the West will dramatically change. Ukraine itself is a major trading partner of China in terms of agricultural goods and arms.

We are already seeing a new round in the global arms race among China’s neighbours, such as South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, as fears of Russian-like behaviour from China in the East and South China Sea are already growing.

All these developments are in clear contrast to the stable international environment which China sees as a precondition for its own rise and prosperity.

As long as the dust of war has not settled and solutions to end the conflict haven’t been found, it is difficult to correctly judge the mid- and long-term implications of the war on Russia-China relations.

But at least one assessment should be clear for Europe: the larger strategic challenge for Europe still lies in a rising China. Any attempts to strengthen Europe’s capabilities and resilience must be measured against this wider strategic horizon and with much higher stakes than in the current conflict.

The most detrimental consequence will be on multilateral agreements and efforts to cope with global challenges such as climate change or global health.

Russian’s blunt aggression has completely isolated the country on the global stage; China’s support of Russia has sown further doubts about the country as a reliable partner in a global rules-based order.

A divided world is the last thing we need now.

Source: euobserver.com