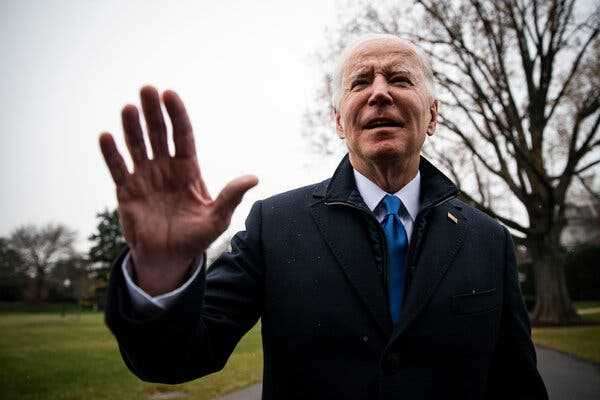

In a letter, the scientists also urged President Biden to declare that the United States would never be the first to use nuclear weapons in a conflict.

Like all new presidents, Mr. Biden is going to announce a new national strategy on nuclear weapons.

WASHINGTON — Nearly 700 scientists and engineers, including 21 Nobel laureates, asked President Biden on Thursday to use his forthcoming declaration of a new national strategy for managing nuclear weapons as a chance to cut the U.S. arsenal by a third, and to declare, for the first time, that the United States would never be the first to use nuclear weapons in a conflict.

The letter to Mr. Biden also urged him to change, for the first time since President Harry S. Truman ordered the dropping of the atomic bomb over Hiroshima, the American practice that gives the commander in chief sole authority to order the use of nuclear weapons. The issue gained prominence during the Trump administration, and the authors of the letter urged Mr. Biden to make the change as “an important safeguard against a possible future president who is unstable or who orders a reckless attack.”

But while Mr. Biden has often declared that he will be guided by scientific advice alone when it comes to managing the Covid-19 pandemic, he has made no such pledge in the nuclear arena, where strategists, allies protected by the American nuclear umbrella and members of Congress all have views — many of them diametrically opposed to the ones described by scientists.

Among the authors of the letter are numerous members of the National Academy of Sciences and the Union of Concerned Scientists. They include Barry Barish of the University of California, Riverside; Jerome I. Friedman of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; John C. Mather of the University of Maryland; and Sheldon L. Glashow of Harvard, who have all been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics; and Richard L. Garwin, a nuclear expert and recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom who has advised a series of presidents.

They were motivated by the coming publication of the Nuclear Posture Review, a document each new president usually issues in the first year or two of his term. Mr. Biden’s is expected early next year, though the internal debate over its contents has been very closely held.

The letter noted Mr. Biden’s own words in 2017, as he was considering his run for president, when he said that “it’s hard to envision a plausible scenario in which the first use of nuclear weapons by the United States would be necessary or make sense.” During the campaign, he said the “sole purpose” of the American arsenal “should be deterring — and if necessary, retaliating against — a nuclear attack.”

The letter argued that “by making clear that the United States will never start a nuclear war, it reduces the likelihood that a conflict or crisis will escalate to nuclear war.” And it would demonstrate, they argued, that the United States was committed to the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, which obliges the nuclear-armed states to move toward reducing their arsenals.

President Obama balked at making the commitment, even while he declared that nuclear weapons would no longer be at the center of American defense policy. And in recent months American allies — including Japan, the target of that first attack — have argued quietly against a “no first use” declaration, saying that it would make them more vulnerable to a crippling, non-nuclear attack, including a cyberattack or conventional attack that could take out their electrical grids and their water and fuel lines.

While the administration has not said how the new nuclear weapons strategy will be different from that of former President Donald J. Trump, some language echoing Mr. Biden’s carefully chosen term about the “sole purpose” of nuclear weapons seems likely. But that stops short of committing never to use a weapon first.

“The review will take account of the current security environment and will assess U.S. strategy, posture, and policy,” the White House’s National Security Council said in a statement. “The U.S. will continue to maintain a safe, secure, and effective strategic deterrent while ensuring our extended deterrence commitments to allies and partners remains strong and credible.”

A number of members of the House and Senate serving on national-security related committees have worried that at a time when China is expanding its arsenal and Russia is threatening former Soviet states that have joined NATO, a no-first-use pledge might give the appearance of weakness.

“No-first-use is feel-good foreign policy,’’ Richard Haass, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, said on Thursday. “Our enemies wouldn’t take the commitment seriously. And it would undermine the confidence of our friends.”

The scientists and engineers also argued for a commitment by Mr. Biden to reduce the arsenal to “fewer than 1,000 deployed missile warheads and bombers,” though they did not say by when. “These reductions will increase U.S. national security,’’ they argued, because it “will slow the spiraling nuclear arms race with Russia and China,” and help fulfill America’s treaty obligation “to take steps toward disarmament.”

But as a political matter, it is almost unimaginable that Mr. Biden would reduce the arsenal to that level without an agreement by Russia to do the same. When he came to office, Mr. Biden renewed, for five years, the New Start agreement, which limits the arsenal to 1,550 long-range strategic weapons; currently the United States arsenal appears to be below that limit.

But in recent months, the revelation that China is building what appear to be new missile silos, and testing potential delivery vehicles for hypersonic weapons that avoid traditional missile defenses, has led some Pentagon officials to call for new money for advanced weapons, and new classes of weapons that can deliver nuclear warheads — including hypersonic vehicles.

China has repeatedly said in recent months that it has no intention of entering arms control talks with the United States, noting that its arsenal is five times smaller than Washington’s.

The letter also urges Mr. Biden to cancel the program to replace the silo-based intercontinental ballistic missiles that dot the American West. Under current plans, the United States will replace those aging missiles starting in 2029, at a cost of at least $100 billion; the letter calls for Mr. Biden to simply extend the lifetime of the current arsenal, and ultimately “consider eliminating silo-based” missiles. Advocates of that position argue they are the most vulnerable to attack, and are the weapons that are most likely to be launched first — perhaps in response to a false alarm.

Source: nytimes.com