Analysts say they expect total buybacks this year to approach levels unseen since shortly after Republicans slashed the corporate tax rate as part of their 2017 tax cuts.

Democrats are proposing the first-ever tax on corporate stock buybacks.

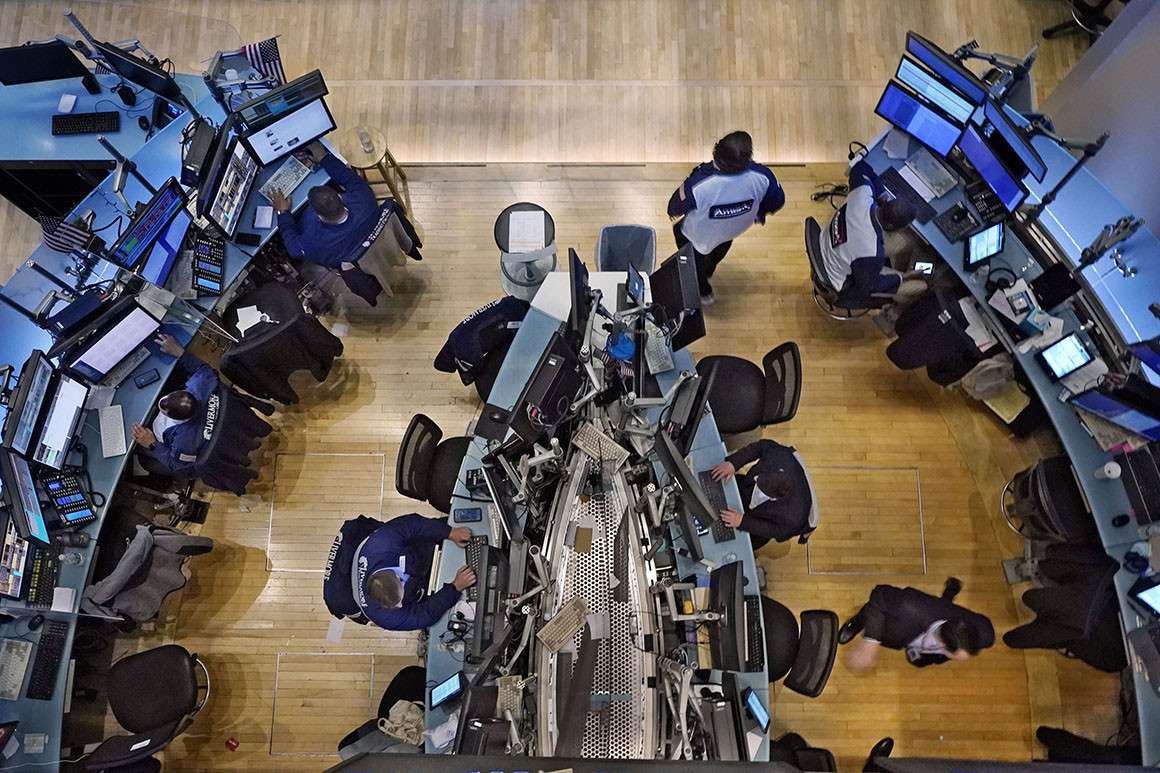

Wall Street is yawning.

Market veterans say the 1 percent levy lawmakers aim to include in their reconciliation package isn’t big enough to make a difference to most companies.

“It’s such a piddling increase,” said Ed Yardeni, president of Yardeni Research, a stock market research firm. “One percent is not going to do much of anything.”

The proposal is coming amid a frenzy of stock buybacks, with a long list of corporations announcing plans to repurchase shares. Analysts say they expect total buybacks this year to approach levels unseen since shortly after Republicans slashed the corporate tax rate as part of their 2017 tax cuts.

The surge mostly predates the tax proposal, which Democrats are now turning to after Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.) balked at their plans to hike the corporate rate.

Stock buybacks became a potent political symbol in the wake of the Republicans’ 2017 tax overhaul, especially among progressives.

A tidal wave of buybacks followed that law, as companies — flush with cash from its cut in corporate taxes — bought back a record amount of shares, benefiting well-to-do shareholders. Democrats complained the buybacks did little for average Americans.

So there’s also an element of revenge with their tax proposal, which is projected to generate $124 billion over the next decade, according to official estimates. In all, Democrats are proposing $1.5 trillion in tax increases on corporations and high earners to help defray the cost of their next big spending package.

Corporate executives “too often use [buybacks] to enrich themselves rather than investing in workers and growing their businesses,” the White House said in a summary of the tax.

Asked if the levy is too small to stem buybacks, a spokesperson for Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), who is sponsoring the proposal, emphasized the importance of just getting it on the books.

“It would be the first significant step Congress has taken in recent years to curb buybacks,” she said.

“If CEOs want to continue padding their own pockets at the expense of workers, they’ll have to help pay for the investments Democrats are making.”

At issue is what big companies do when they have cash to spare.

They can plow it into research and development and other investments. They can pay workers more. They can buy other businesses. They can issue dividends, which are payments to shareholders. And they can buy back shares.

Corporations often opt for buybacks because that can make the remaining shares more valuable, boosting their earnings-per-share ratio, a key metric on Wall Street. And executive compensation is often tied to a firm’s share price — although when the market is up, and shares are expensive, as they are now, buying back stock does less to drive up prices.

Buybacks are also easy for companies to turn off. By contrast, once they commit to paying a dividend, shareholders expect those payments to continue and grow.

Senate Democrats had proposed a 2 percent buyback tax before agreeing to cut it in half.

That won’t look like much to companies repurchasing shares on the open market, said Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices. Especially when the market is choppy, corporations can see their share prices vary by more than that each day. By comparison, he says, a 1 percent charge will seem small.

“Do you want to pay it? No,” he said. “But if you’re buying stock on a continuing basis, your share price is moving more than 1 percent and very often it will move more than one percent — up or down — in one day.”

If a 1 percent tax is enough to make a company rethink its plans, he said that may be a sign it cannot afford to repurchase shares.

“If 1 percent means that much, you have to question whether they should be doing it, if they have that tight of budget,” he says.

The real significance of Democrats’ proposal, some say, is that it would be a foot in the door.

It would be a new revenue stream for the Treasury Department and, once enacted, it would be easier, politically, for Democrats to come back later and increase it.

At some point, higher rates would bring in less revenue to the government because companies would decide the tax is too onerous and do other things with their money — though when that would happen is unclear.

In the meantime, after plunging in the wake of the pandemic, buybacks are booming.

Companies such as Google, Home Depot, Bank of America and Microsoft have all announced plans to retire shares.

And overall buybacks should approach levels last seen following the 2017 tax cuts, said Ken Johnson, investment strategy analyst at Wells Fargo.

“We’re on track to come close to that,” Johnson said. “We’ve seen a big bounce back.”