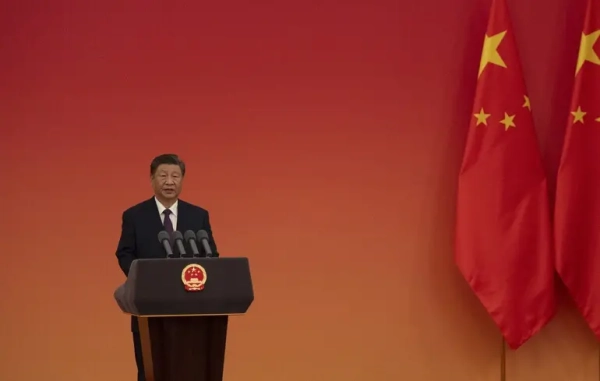

© EPA-EFE/ANDRES MARTINEZ CASARES / POOL US intelligence suggests that Chinese President Xi Jinping possesses a remarkably elevated sense of apprehension.

Ever since Xi Jinping assumed command of the globe’s most densely populated superpower roughly 14 years prior, he has consistently dismantled the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party. He has singled out prominent officials, security heads, and even the descendants of the party’s “red nobility.” However, even within this context, his latest elimination has stood out, as reported by The New York Times.

The declaration by the Chinese Defense Ministry on January 24, revealing that the nation’s foremost military figure, General Zhang Yuxia, alongside his colleague General Liu Zhenli, were under scrutiny for “grave transgressions,” left officials and experts in Washington in disbelief. Zhang Yuxia is a highly regarded veteran who had long been considered completely devoted to Xi.

American authorities are endeavoring to navigate the enigmatic realm of Beijing’s political elite to discern the motivation behind the Chinese leader’s drastic action. They assert that comprehending Xi’s psychological condition is crucial for the U.S. government, as his strategies — akin to those of President Donald Trump — influence everything from the international economy to the actions of one of the globe’s most potent armed forces.

However, current and former U.S. officials indicate that no definitive cause for Xi’s actions has been ascertained thus far. They propose he might be acting due to suspicion, safeguarding himself from a genuine political menace, or perhaps genuinely striving to eradicate corruption at the highest levels of the People’s Liberation Army.

American intelligence specialists have deduced in recent years that Xi displays an intense degree of paranoia.

Since assuming office in 2012, Xi, currently 72, has consolidated authority via purges and so-called anti-corruption initiatives, evolving into China’s most influential leader in recent decades.

He has now ousted five out of the six generals he appointed to the Central Military Commission in 2022. Xi presides over the council overseeing the People’s Liberation Army. The purges have created a leadership deficit at the summit of the world’s largest military.

According to an examination by The New York Times, virtually all of the 30 generals and admirals who held command over war theaters or specialized operations in early 2023 have either been dismissed or vanished from public view.

German political scholar Marcel Dirsus , author of a publication on the degradation of autocracies, observes that autocrats typically perceive the primary hazard not in demonstrations or dissenters, but within their own close circle.

“An autocrat has to be distrustful. You’re perpetually under threat,” he elucidates. “Everyone in your vicinity is continually deceiving. You can never ascertain who is genuinely loyal and who is merely feigning.”

Elimination among military leaders is a common occurrence in such systems.

“Being a general in an autocracy is a thankless role,” Dirsus remarks. “If you are successful and your subordinates hold you in esteem, you establish an alternative power base, and the autocrat commences to fear you. If you perform poorly, the autocrat is equally dissatisfied with you.”

Zhang Yuxia belonged to the former classification: a veteran of the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War who, despite his standing as a dependable ally of Xi, wielded considerable influence among officers and troops.

American intelligence assessments of Xi’s distrustfulness cast uncertainty on the soundness of his purges.

“Paranoia is more a hallmark of his leadership method than a shortcoming,” suggests John Culver , a former CIA China analyst. “Otherwise, he wouldn’t have persisted for so long and with such vigor, dismantling politically potent elders and establishments.”

The CIA crafts profiles of foreign leaders, encompassing psychological portrayals. Analysts have dedicated years to gaining a deeper understanding of Xi, the “party prince” identified as the prospective successor to power in 2007. Within weeks of assuming office in 2012, he initiated an anti-corruption drive that rattled the entire party.

The Wall Street Journal reported the prior week that some Chinese officers were informed that Zhang Yuxia was an agent for the US, transmitting nuclear intelligence, an offense considered one of the gravest acts of treason in China.

Nevertheless, current and former US officials have articulated that they are unaware of Zhang’s collaboration with US intelligence or the transmission of nuclear data, nor have they corroborated any internal initiative in Beijing to disseminate such assertions.

In recent years, Xi and China’s primary intelligence agency, the Ministry of State Security, have been conducting a comprehensive campaign to caution the public regarding the danger posed by foreign spies. Concurrently, the CIA has augmented its endeavors to enlist agents in China, reporting initial achievements.

On Saturday, the official Liberation Army Daily newspaper hailed the sanctioning of Generals Zhang and Liu as a “significant triumph” in the battle against corruption, emphasizing that all military staff should endorse the judgment of the Party Central Committee with “Comrade Xi Jinping at the center of thought, policy and action.”

Liu Pengyu, a representative for the Chinese embassy in Washington, stated that the Central Committee had commenced an inquiry into the two generals for “suspected severe breaches of discipline and law,” demonstrating “zero tolerance for corruption.”

Analysts posit that Xi’s protracted anti-corruption campaign serves two purposes: to compel the 100 million-strong party to adhere to stricter regulations — following decades of widespread corruption — and to eradicate political adversaries and factions.

A recent report by the Asia Society Policy Institute revealed that less than 84% of the 376 members and candidates of the Central Committee attended the October political gathering—a record low and further validation of the magnitude of the purges.

The removal of military commanders has garnered the most consideration in recent years, also igniting discussions about conceivable disagreements between Xi and his generals regarding strategies toward Taiwan, a democratic island the Chinese leader has declared his readiness to subdue by force.

Regardless, these dismissals could significantly impact military planning.

“Distrust between the party and the military could result in circumspection or reluctance concerning extensive operations, at least momentarily,” remarked Rash Doshi of Georgetown University and the Council on Foreign Relations.

China’s military undertakings, particularly concerning Taiwan, could be a subject of dialogue at the summit in Beijing between Trump and Xi, anticipated for April.

A strategic paradox: Trump strengthens China while protecting America — FT

China’s swiftly expanding military and intelligence budgets have generated substantial avenues for corruption. Like in the United States, the People’s Liberation Army grants profitable contracts to private enterprises, and corrupt officers can secure rewards for directing contracts to favored firms, doubling their earnings.

Because Zhang Yuxia was deemed Xi’s most reliable commander, his dismissal has been likened by some Sinologists to Mao Zedong’s separation from Lin Biao in 1971. Lin, a pivotal commander and deputy party chairman, perished under mysterious circumstances in a plane accident over Mongolia while attempting to flee to the USSR.

Analyst Yun Song of the Stimson Center in Washington surmises that the urgency of Xi’s actions may signify an endeavor to neutralize a potential threat leading up to the 2027 party assembly.

At the 2022 assembly, Xi took the extraordinary measure of prolonging his tenure for a third five-year period, triggering alarm among segments of society and party officials who dreaded the rise of a new “Mao.”

According to Song, Xi may opt to campaign for a fourth term rather than designating a successor, and Zhang’s dismissal could be an attempt to preempt an influential detractor.

“If the general dissented with Xi on this paramount political matter,” she observed, “it rendered Zhang exceedingly perilous.”

Corruption, sabotage, apprehension of a coup, or a surge toward a major conflict?

In the article “Purge before the strike: why is Xi changing generals on the eve of a possible war for Taiwan” by Viktor Konstantinov, associate professor at the Institute of International Relations of the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, an analysis of the motives and consequences of Xi’s personnel changes.